(Press-News.org) Peek inside the human genome and, among the 20,000 or so genes that serve as building blocks of life, you’ll also find flecks of DNA left behind by viruses that infected primate ancestors tens of millions of years ago.

These ancient hitchhikers, known as endogenous retroviruses, were long considered inert or ‘junk’ DNA, defanged of any ability to do damage. New CU Boulder research published July 17 in the journal Science Advances shows that, when reawakened, they can play a critical role in helping cancer survive and thrive. The study also suggests that silencing certain endogenous retroviruses can make cancer treatments work better.

“Our study shows that diseases today can be significantly influenced by these ancient viral infections that until recently very few researchers were paying attention to,” said senior author Edward Chuong, an assistant professor of molecular, cellular and developmental biology at CU’s BioFrontiers Institute.

Part human, part virus

Studies show about 8% of the human genome is made up of endogenous retroviruses that slipped into the cells of our evolutionary ancestors, coaxing their hosts to copy and carry their genetic material. Over time, they infiltrated sperm, eggs and embryos, baking their DNA like a fossil record into generations to come —and shaping evolution along the way.

Even though they can no longer produce functional viruses, Chuong’s own research has shown that endogenous retroviruses can act as “switches” that turn on nearby genes. Some have contributed to the development of the placenta, a critical milestone in human evolution, as well as our immune response to modern-day viruses like COVID.

“There’s been a lot of work showing these endogenous retroviruses can be domesticated for our benefit, but not a lot showing how they might hurt us,” he said.

To explore their role in cancer, Chuong and first author Atma Ivancevic, a research associate in his lab, analyzed genomic data from 21 human cancer types from publicly available datasets.

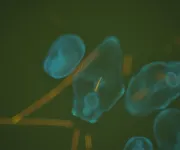

They found that a specific lineage of endogenous retrovirus known as LTR10, which infected some primates about 30 million years ago, showed surprisingly high levels of activity in several types of cancer, including lung and colon cancer. Further analysis of tumors from dozens of colorectal cancer patients revealed that LTR10 was active in about a third of them.

When the team used the CRISPR gene editing tool to snip out or silence sequences where it was present, they discovered that critical genes known to promote cancer development and growth also went dark.

“We saw that when you silence this retrovirus in cancer cells, it turns off nearby gene expression,” said Ivancevic.

Experiments in mice yielded similar results: When an LTR10 “switch” was removed from tumor cells, key cancer-promoting genes, including one called XRCC4, switched off too, and treatments to shrink tumors worked better.

“We know that cancer cells express a lot of genes that are not supposed to be on, but no one really knows what is turning them on,” said Chuong. “It turns out many of the switches turning them on are derived from these ancient viruses.”

Insight into how existing therapies work

Notably, the endogenous retrovirus they studied appears to switch on genes in what is known as the MAP-kinase pathway, a famed cellular pathway that is adversely rewired in many cancers. Existing drugs, known as MAP-kinase inhibitors, likely work, in part, by disabling the endogenous retrovirus switch, the study suggests.

The authors note that just this one family of retrovirus regulates as many as 70 cancer-associated genes in this pathway. Different lineages likely influence different pathways that promote different cancers.

Chuong suspects that as people age, their genomic defenses break down, enabling ancient viruses to reawaken and contribute to other health problems too.

“The origins of how diseases manifest themselves in the cell have always been a mystery,” said Chuong. “Endogenous retroviruses are not the whole story, but they could be a big part of it.”

END

Study shows ancient viruses fuel modern-day cancers

Therapies to silence 'endogenous retroviruses' could make cancer treatments work better

2024-07-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Reef pest feasts on 'sea sawdust'

2024-07-17

Researchers have uncovered an under-the-sea phenomenon where coral-destroying crown-of-thorns starfish larvae have been feasting on blue-green algae bacteria known as ‘sea sawdust’.

The team of marine scientists from The University of Queensland and Southern Cross University found crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS) larvae grow and thrive when raised on an exclusive diet of Trichodesmium – a bacteria that often floats on the ocean’s surface in large slicks.

UQ’s Dr Benjamin Mos from the School ...

Mental health training for line managers linked to better business performance, says new study

2024-07-17

Mental health training for line managers is strongly linked to better business performance, and it could save companies millions of pounds in lost sick days every year, according to new research led by experts at the University of Nottingham.

The results of the study, which are published in PLOS ONE, showed a strong association between mental health training for line managers and improved staff recruitment and retention, better customer service, and lower levels of long-term mental health sickness absence.

The study was led by Professor Holly Blake from the School of Health Sciences at the University of Nottingham and Dr Juliet Hassard of Queen’s ...

Diatom surprise could rewrite the global carbon cycle

2024-07-17

When it comes to diatoms that live in the ocean, new research suggests that photosynthesis is not the only strategy for accumulating carbon. Instead, these single-celled plankton are also building biomass by feeding directly on organic carbon in wide swaths of the ocean. These new findings could lead researchers to reduce their estimate of how much carbon dioxide diatoms pull out of the air via photosynthesis, which in turn, could alter our understanding of the global carbon cycle, which is especially relevant given the changing climate.

This research is led by bioengineers, bioinformatics experts and other genomics researchers ...

Microbes found to destroy certain ‘forever chemicals’

2024-07-17

UC Riverside environmental engineering team has discovered specific bacterial species that can destroy certain kinds of “forever chemicals,” a step further toward low-cost treatments of contaminated drinking water sources.

The microorganisms belong to the genus Acetobacterium and they are commonly found in wastewater environments throughout the world.

Forever chemicals, also known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS, are so named because they have stubbornly strong carbon-fluorine chemical bonds, which make them persistent in the environment.

The microorganisms discovered by UCR scientists and their collaborators ...

When the brain speaks, the heart feels it

2024-07-17

Research by the Technion has demonstrated that activation of the brain’s reward system could boost recovery from a heart attack. The research, which was conducted at the Ruth and Bruce Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, was led by Ph.D. student Hedva Haykin under the supervision of Prof. Asya Rolls and Prof. Lior Gepstein.

The Technion research group focused on the reward system, a brain network activated in positive emotional states and motivation and evaluated its potential in improving recovery ...

Llama nanobodies: A breakthrough in building HIV immunity

2024-07-17

ATLANTA — A research team at Georgia State University has developed tiny, potent molecules that are capable of targeting hidden strains of HIV. The source? Antibody genes from llama DNA.

The research, led by Assistant Professor of Biology Jianliang Xu, uses llama-derived nanobodies to broadly neutralize numerous strains of HIV-1, the most common form of the virus. A new study from this team has been published in the journal Advanced Science.

“This virus has evolved a way to escape our immune system. Conventional antibodies are bulky, so it’s difficult for them to find and attack the virus’ surface,” ...

How our brains learn new athletic skills fast

2024-07-17

You join a swing dance class, and at first you’re all left feet. But – slowly, eyes glued to the teacher – you pick up a step or two and start to feel the rhythm of the big band beat. A good start.

Then you look over and realize the couple next to you has picked up twice the steps in half the time.

Why?

According to a new study from University of Florida biomechanical researchers, the quick, athletic learners among us really are built differently – inside their brains.

That’s what UF Professor of Biomedical Engineering Daniel Ferris, Ph.D., and his former doctoral student, Noelle Jacobsen, Ph.D., discovered when they studied how people learn ...

New Durham University study shows promising diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis from images of the eye

2024-07-17

-With images-

Researchers at Durham University, UK and Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Iran have developed an innovative approach to diagnosing Multiple Sclerosis using advanced eye imaging techniques.

This groundbreaking method could revolutionise how Multiple Sclerosis is detected, offering a faster, less invasive, and more accessible alternative to current diagnostic procedures.

The study, led by Dr Raheleh Kafieh of Durham University, integrates two types of eye scans: optical coherence tomography (OCT) and infrared scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (IR-SLO).

By training computer models ...

New training program facilitates home-based transcranial electrical stimulation

2024-07-17

Traveling to and from a clinic or a laboratory for treatment can be difficult and expensive for older Americans. To address this, scientists developed and tested a new training and supervision program for older adults so they can receive Transcranial Electrical Stimulation (tES), a promising intervention for various clinical conditions, in their homes.

Published in Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface, this groundbreaking training and supervision program was designed to introduce and teach caregivers, family members, and patients how to administer home-based transcranial electrical stimulation (HB-tES), equipping them ...

Study finds persistent proteins may influence metabolomics results

2024-07-17

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (July 17, 2024) — Van Andel Institute scientists have identified more than 1,000 previously undetected proteins in common metabolite samples, which persist despite extraction methods designed to weed them out.

The findings, published in Nature Communications, give scientists new insights and tools for improving future metabolomics experiments, including a novel protocol for removing these proteins during the extraction process. The study does not invalidate prior results but instead reinforces the importance ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Noise pollution is affecting birds' reproduction, stress levels and more. The good news is we can fix it.

Researchers identify cleaner ways to burn biomass using new environmental impact metric

Avian malaria widespread across Hawaiʻi bird communities, new UH study finds

New study improves accuracy in tracking ammonia pollution sources

Scientists turn agricultural waste into powerful material that removes excess nutrients from water

Tracking whether California’s criminal courts deliver racial justice

Aerobic exercise may be most effective for relieving depression/anxiety symptoms

School restrictive smartphone policies may save a small amount of money by reducing staff costs

UCLA report reveals a significant global palliative care gap among children

The psychology of self-driving cars: Why the technology doesn’t suit human brains

Scientists discover new DNA-binding proteins from extreme environments that could improve disease diagnosis

Rapid response launched to tackle new yellow rust strains threatening UK wheat

How many times will we fall passionately in love? New Kinsey Institute study offers first-ever answer

Bridging eye disease care with addiction services

Study finds declining perception of safety of COVID-19, flu, and MMR vaccines

The genetics of anxiety: Landmark study highlights risk and resilience

How UCLA scientists helped reimagine a forgotten battery design from Thomas Edison

Dementia Care Aware collaborates with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement to advance age-friendly health systems

Growth of spreading pancreatic cancer fueled by 'under-appreciated' epigenetic changes

Lehigh University professor Israel E. Wachs elected to National Academy of Engineering

Brain stimulation can nudge people to behave less selfishly

Shorter treatment regimens are safe options for preventing active tuberculosis

How food shortages reprogram the immune system’s response to infection

The wild physics that keeps your body’s electrical system flowing smoothly

From lab bench to bedside – research in mice leads to answers for undiagnosed human neurodevelopmental conditions

More banks mean higher costs for borrowers

Mohebbi, Manic, & Aslani receive funding for study of scalable AI-driven cybersecurity for small & medium critical manufacturing

Media coverage of Asian American Olympians functioned as 'loyalty test'

University of South Alabama Research named Top 10 Scientific Breakthroughs of 2025

Genotype-specific response to 144-week entecavir therapy for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B with a particular focus on histological improvement

[Press-News.org] Study shows ancient viruses fuel modern-day cancersTherapies to silence 'endogenous retroviruses' could make cancer treatments work better