(Press-News.org) New research from scientists at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography finds a tiny freshwater parasite known to cause health problems in humans defends its colonies with a class of soldiers that cannot reproduce.

The discovery, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and funded by the National Institutes of Health, vaults this species of parasitic flatworm into the ranks of complex animal societies such as ants, bees and termites, which also have distinct classes of workers and soldiers that have given up reproduction to serve their colony.

When it gets into humans, usually via the consumption of raw or undercooked fish, this species of flatworm, Haplorchis pumilio, can cause gastrointestinal issues and in severe cases stroke or heart attack. Fully cooking fish or freezing any meant to be eaten raw for at least one week is enough to kill the trematodes, per Food and Drug Administration guidelines. While there are no specific statistics for Haplorchis pumilio, foodborne trematode infections cause 2 million life years lost to disability and death worldwide every year.

Unlike bees and termites, the colonies of this species of flatworm are not underground or in a tree hollow, but inside the body of a live snail. The parasites don’t kill the snail, but instead siphon off nutrients for years as they pump out free-swimming clones that search for fish, the flatworms’ next host in their complex life cycle.

“Compared to bees or termites, you can fit way more colonies from these flatworms in the lab,” said Ryan Hechinger, an ecologist at Scripps and the study’s senior author. “These flatworms could become invaluable tools to probe fundamental questions of sociobiology – like, ‘how does this kind of social organization evolve?’”

While some other species in this class of parasitic flatworms, called trematodes, also have soldiers, those species’ soldiers may still contain some inactive reproductive tissue, suggesting they can become reproductive at some point. This study is the first evidence for trematode soldiers that are so physically specialized to their task that they lack any reproductive tissues and appear permanently incapable of reproduction, said Hechinger.

Haplorchis pumilio forms nest-like colonies inside the freshwater snail Melanoides tuberculata and then infects two other successive hosts during its life cycle – typically fish and finally a warm-blooded vertebrate. Both the trematode and the snail are native to Africa and southern Asia but are co-invasive in the Americas, including California, Texas and Florida.

The phase of this trematode’s life cycle when it forms a colony inside the snail is where researchers encountered the soldier caste. The soldiers defend the colony against interlopers – such as other parasites – using a large mouth that creates powerful suction capable of ripping holes in its enemies and sucking out their insides.

“These worms want to guard their house,” said Dan Metz, the paper’s lead author and a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln who conducted this study during his PhD at Scripps. “Another parasite infecting their snail is like someone coming into your home and threatening your family. You’ll do what you can to protect your family, and so will these worms.”

Metz encountered these worms somewhat serendipitously. On a walk around Lake Murray in San Diego, Calif., he saw an unfamiliar snail at the water’s edge and took it back to the lab. It turned out the snail was Melanoides tuberculata and it was also infected by the trematode Haplorchis pumilio.

Upon taking a closer look at the colony of parasites, Metz and Hechinger noticed that many members of the colony were about half as long and differently proportioned than the rest. These smaller worms turned out to be the soldiers, which, despite being less than half a millimeter long (0.02 inches), had mouths five-times larger than those of their much larger, reproductively capable counterparts.

“These soldiers are really just mobile jaws,” said Metz. “Their whole function is to bite things.”

Through experiments and close examination, Metz and Hechinger uncovered multiple lines of evidence that suggest these soldiers are totally different from their reproductively capable kin inside the colony.

First, all the soldiers lacked any reproductive organs, while even the most immature reproductive worms – including unborn ones still inside their parent – had detectable reproductive structures. Second, the researchers did not encounter any worms that had body proportions that appeared to bridge the physical gap between soldiers and the reproductive worms. Soldiers of all sizes had relatively massive maws compared to their overall body size while no reproductive worms approached the soldiers’ mouth-centric proportions. And third, the researchers showed through experimental trials that soldiers consistently attacked other parasites, while reproductive worms showed almost no aggressive behavior.

The study also showed that having dedicated soldiers appears to facilitate ecological dominance for this trematode species, at least in its invasive range in Southern California. Among other species of trematodes that have also invaded Southern California and that infect the same snail, the researchers calculated that the soldier-producing species caused around 94% of all of the deaths that occurred among the different species. This superior firepower in trematode conflict led the abundances of the other trematode species to be much lower than they would otherwise be.

“The soldiers don’t infect humans – they are only in the snails,” said Metz. “A different stage in the worm’s life cycle infects warm-blooded vertebrates, including people, but having soldiers makes this parasite more successful at infecting snails, which means more opportunities to transmit to people.”

This parasite is spreading globally and understanding its biology could be important for public health as well as for understanding the evolutionary roots of complex social organization. There may also be many more species of trematodes with permanent soldier castes.

“We’ve really barely started looking,” said Hechinger. “There may be up to 200,000 species of trematode on the planet, and we’ve only looked at a few of them in the context of social organization. There is a lot more waiting to be discovered concerning the ways by which trematodes create complex societies with division of labor.”

END

Human-infecting parasite produces sterile soldiers like ants and termites

This species of freshwater flatworm could be used to study the evolution of social organization

2024-07-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The unintended consequences of success against malaria

2024-07-24

For decades, insecticide-treated bed nets and indoor insecticide spraying regimens have been important – and widely successful – treatments against mosquitoes that transmit malaria, a dangerous global disease. Yet these treatments also – for a time – suppressed undesirable household insects like bed bugs, cockroaches and flies.

Now, a new North Carolina State University study reviewing the academic literature on indoor pest control shows that as the household insects developed resistance ...

Taco-shaped arthropod from Royal Ontario Museum’s Burgess Shale fossils gives new insights into the history of the first mandibulates

2024-07-24

A new study, led by palaeontologists at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) is helping resolve the evolution and ecology of Odaraia, a taco-shaped marine animal that lived during the Cambrian period. Fossils collected by ROM reveal Odaraia had mandibles. Palaeontologists are finally able to place it as belonging to the mandibulates, ending its long enigmatic classification among the arthropods since it was first discovered in the Burgess Shale over 100 years ago and revealing more about early evolution and diversification. The study The Cambrian Odaraia alata and the colonization of nektonic suspension-feeding niches by early mandibulates was published ...

Butterflies accumulate enough static electricity to attract pollen without contact, new research finds

2024-07-24

Butterflies and moths collect so much static electricity whilst in flight, that pollen grains from flowers can be pulled by static electricity across air gaps of several millimetres or centimetres.

The finding, published today in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, suggests that this likely increases their efficiency and effectiveness as pollinators.

The University of Bristol team also observed that the amount of static electricity carried by butterflies and moths varies between different species, and that these variations correlate with differences in their ecology, such as whether they visit flowers, are ...

Eyes for Love: Searching for light and a mate in the deep, dark sea, male dragonfishes grow larger eyes than the females they seek

2024-07-24

Chestnut Hill, Mass (07/24/2024) – A small but ferocious predator, the male dragonfish will apparently do anything for love. Or at least to find a mate.

A new study by researchers at Boston College found the eyes of the male dragonfish grow larger for mate-seeking purposes, making the dragonfish an anomaly in vertebrate evolution, the team reported today in the Royal Society journal Biology Letters.

Like many creatures that inhabit the dark depths of the sea, dragonfishes survive thanks to numerous ...

PNNL scientists tap nation’s fastest computers to explore critical science questions

2024-07-24

RICHLAND, Wash.—Researchers at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory have been awarded more than 3 million node hours on the nation’s most powerful computers to explore questions around pathogens, climate and energy-efficient microelectronics.

Access to the nation’s supercomputers, granted to Margaret Cheung, Daniel Mejia Rodriguez and Po-Lun Ma, is a coveted prize among scientists. The node hours represent an investment of several million dollars in computing time awarded to PNNL scientists to explore important science questions.

The awards are among 44 projects awarded through ...

Peri-operative care of transgender and gender-diverse individuals: new guidance for clinicians and departments published

2024-07-24

New guidance on peri-operative care of transgender and gender-diverse individuals is today published in Anaesthesia (the journal of the Association of Anaesthetists) to guide best practice to ensure the safety and dignity of transgender and gender-diverse people in the peri-operative period. The guidance has been produced by a working group of experts including Dr Stuart Edwardson, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, and Dr Luke Flower, Victor Philip Dahdaleh Heart and Lung Research Institute, Cambridge, UK, and colleagues.

The number of people openly identifying ...

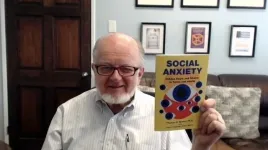

Clinical psychologist’s book addresses largely ignored problem: social anxiety

2024-07-23

RIVERISDE, Calif. -- We all have some social anxiety. The nervousness we might feel before giving a speech is one example. Some people, however, have more social anxiety than others, and limit their social engagement due to excessive chronic fears of being embarrassed or humiliated. Although such social anxiety is common in both adolescents and adults, it is rarely diagnosed and treated.

In a new book titled “Social Anxiety: Hidden Fears and Shame in Teens and Adults,” Thomas E. Brown, a clinical professor of psychiatry and neuroscience in the University of California, Riverside's School of Medicine , explains ...

Researchers leveraging AI to train (robotic) dogs to respond to their masters

2024-07-23

An international collaboration seeks to innovate the future of how a mechanical man’s best friend interacts with its owner, using a combination of AI and edge computing called edge intelligence.

The project is sponsored through a one-year seed grant from the Institute for Future Technologies (IFT), a partnership between New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT) and Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU).

Assistant Professor Kasthuri Jayarajah in NJIT’s Ying Wu College of Computing is researching how to design a socially assistive model ...

Drawing water from dry air

2024-07-23

Earth’s atmosphere holds an ocean of water, enough liquid to fill Utah’s Great Salt Lake 800 times.

Extracting some of that moisture is seen as a potential way to provide clean drinking water to billions of people globally who face chronic shortages.

Existing technologies for atmospheric water harvesting (AWH) are saddled with numerous downsides associated with size, cost and efficiency. But new research from University of Utah engineering researchers has yielded insights that could improve efficiencies and bring the world one step closer to tapping the air as a culinary water source in arid places.

The study unveils the first-of-its-kind ...

Combining trapped atoms and photonics for new quantum devices

2024-07-23

Quantum information systems offer faster, more powerful computing methods than standard computers to help solve many of the world’s toughest problems. Yet fulfilling this ultimate promise will require bigger and more interconnected quantum computers than scientists have yet built. Scaling quantum systems up to larger sizes, and connecting multiple systems, has proved challenging.

Now, researchers at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) have discovered how to combine two powerful technologies—trapped atom arrays and photonic devices—to ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

Can Europe be climate-neutral by 2050? New monitor tracks the pace of the energy transition

Major heart attack study reveals ‘survival paradox’: Frail men at higher risk of death than women despite better treatment

Medicare patients get different stroke care depending on plan, analysis reveals

Polyploidy-induced senescence may drive aging, tissue repair, and cancer risk

Study shows that treating patients with lifestyle medicine may help reduce clinician burnout

Experimental and numerical framework for acoustic streaming prediction in mid-air phased arrays

Ancestral motif enables broad DNA binding by NIN, a master regulator of rhizobial symbiosis

Macrophage immune cells need constant reminders to retain memories of prior infections

Ultra-endurance running may accelerate aging and breakdown of red blood cells

Ancient mind-body practice proven to lower blood pressure in clinical trial

SwRI to create advanced Product Lifecycle Management system for the Air Force

Natural selection operates on multiple levels, comprehensive review of scientific studies shows

Developing a national research program on liquid metals for fusion

AI-powered ECG could help guide lifelong heart monitoring for patients with repaired tetralogy of fallot

Global shark bites return to average in 2025, with a smaller proportion in the United States

Millions are unaware of heart risks that don’t start in the heart

What freezing plants in blocks of ice can tell us about the future of Svalbard’s plant communities

A new vascularized tissueoid-on-a-chip model for liver regeneration and transplant rejection

Augmented reality menus may help restaurants attract more customers, improve brand perceptions

Power grids to epidemics: study shows small patterns trigger systemic failures

[Press-News.org] Human-infecting parasite produces sterile soldiers like ants and termitesThis species of freshwater flatworm could be used to study the evolution of social organization