A WEHI study could help solve a long-standing mystery into why a key immune organ in our bodies shrinks and loses its function as we get older.

The thymus is an organ essential for good health due to its ability to produce special immune cells that are responsible for fighting infections and cancer.

In a world-first, researchers have uncovered new cells that drive this ageing process in the thymus – significant findings that could unlock a way to restore function in the thymus and prevent our immunity from waning as we age.

Watch and embed the video: https://youtu.be/2x1UGqNh77w

At a glance

The thymus is an organ essential for our immune defence but it shrinks and weakens as we get older. The reason for this loss remains a long-standing mystery.

A new study has been able to visualise, for the first time, how two cell types drive this ageing process and cause the thymus to lose its function and regeneration abilities over time.

The findings could help uncover a way to stop the thymus from ageing and, critically, develop methods to restore immunity in vulnerable people in the future.

T cells, also known as T lymphocytes, are a type of white blood cell that plays a crucial role in our immune system. T cells are essential for identifying and responding to pathogens, such as viruses and bacteria, and for eliminating infected or cancerous cells.

The thymus is a small, but mighty, organ that sits behind the breastbone. It is the only organ in the body that can make T cells.

But a curious feature of the thymus is that it is the first organ in our bodies to shrink as we get older. As this happens, the T cell growth areas in the thymus are replaced with fatty tissue, diminishing T cell production and contributing to a weakened immune system.

While the thymus is capable of regenerating from damage, to date researchers have been unable to figure out how to unlock this ability and boost immunity in humans as we age.

WEHI Laboratory Head Professor Daniel Gray said the new findings, published in Nature Immunology, could help solve this mystery that has stumped researchers for decades.

“The number of new T cells produced in the body significantly declines after puberty, irrespective of how fit you are. By age 65, the thymus has virtually retired,” Prof Gray said.

“This weakening of the thymus makes it harder for the body to deal with new infections, cancers and regulate immunity as we age.

“This is also why adults who have depleted immune systems, for example due to cancer treatment or stem cell transplants, take much longer than children to recover.

“These adults need years to recover their T cells – or sometimes never do – putting them at higher risk of contracting potentially life-threatening infections for the rest of their lives.

“Exploring ways to restore thymic function is critical to finding new therapies that can improve outcomes for these vulnerable patients and find a way to ensure a healthy level of T cells are produced throughout our lives.”

The new study, an international collaboration with groups at the Fred Hutch Cancer Center (Seattle) and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Centre (NYC), provides crucial new insights that could help achieve this goal.

“Our discovery provides a new angle for thymic regeneration and immune restoration, could unravel a way to boost immune function in vulnerable patients in the future,” Prof Gray said.

Scarring effects

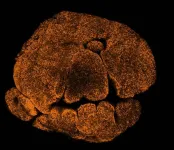

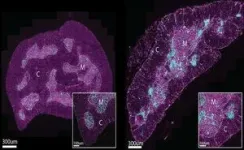

Using advanced imaging techniques at WEHI’s Centre for Dynamic Imaging and animal models, the research team discovered two new cell types that cause the thymus to lose its function.

These cells, which appeared only in the defective thymus of older mice and humans, were found to form clusters around T cell growth areas, impairing the organ’s ability to make these important immune cells.

In a world-first, the researchers discovered these clusters also formed ‘scars’ in the thymus which prevented the organ from restoring itself after damage.

Dr Kelin Zhao, who led the imaging efforts, said the findings showed for the first time how this scarring process acts as a barrier to thymic regeneration and function.

“While a large focus of research into thymic loss of function has focused on the shrinking process, we’ve proven that changes that occur inside the organ also impact its ability to function with age,” Dr Zhao said.

“By capturing these cell clusters in the act and showing how they contribute to loss of thymic function, we’ve been able to do something no one else has ever done before, largely thanks to the incredible advanced imaging platforms we have at WEHI.

“This knowledge enables us to investigate whether these cells can be therapeutically targeted in future, to help turn back the clock on the ageing thymus and boost T cell function in humans as we get older. This is the goal our team is working towards.”

Rich WEHI history

The thymus has deep roots to the institute, with the function of the organ discovered by WEHI Emeritus Professor Jacques Miller in 1958.

While working at the Chester Beatty Research Institute in London, Prof Miller’s work on leukaemia led him to discover that the thymus was crucial to the development of the immune system. He is now credited as the last person to have identified the function of a major organ.

Prof Miller’s discovery revolutionised our understanding of the immune system, infection and disease, with many WEHI researchers – including Prof Daniel Gray’s lab – continuing to build upon his landmark findings.

The new study, “Age-related epithelial defects limit thymic function and regeneration” is published in Nature Immunology (DOI: 10.1038/s41590-024-01915-9)

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Cancer Council of Victoria, the Starr Cancer Consortium, the Tri-Institutional Stem Cell Initiative, The Lymphoma Foundation, The Susan and Peter Solomon Divisional Genomics Program, Cycle for Survival, and the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy and the University of Melbourne Research Training Program Scholarship.

WEHI authors: Kelin Zhao, Michael D’Andrea, Julie Sheridan, Verena Wimmer, Kelly Rogers, Daniel Gray.

END