(Press-News.org) We use the word ‘love’ in a bewildering range of contexts — from sexual adoration to parental love or the love of nature. Now, more comprehensive imaging of the brain may shed light on why we use the same word for such a diverse collection of human experiences.

‘You see your newborn child for the first time. The baby is soft, healthy and hearty — your life’s greatest wonder. You feel love for the little one.’

The above statement was one of many simple scenarios presented to fifty-five parents, self-described as being in a loving relationship. Researchers from Aalto University utilised functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to measure brain activity while subjects mulled brief stories related to six different types of love.

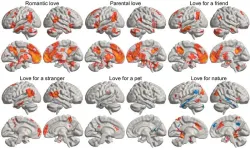

‘We now provide a more comprehensive picture of the brain activity associated with different types of love than previous research,’ says Pärttyli Rinne, the philosopher and researcher who coordinated the study. ‘The activation pattern of love is generated in social situations in the basal ganglia, the midline of the forehead, the precuneus and the temporoparietal junction at the sides of the back of the head.’

Love for one’s children generated the most intense brain activity, closely followed by romantic love.

‘In parental love, there was activation deep in the brain's reward system in the striatum area while imagining love, and this was not seen for any other kind of love,’ says Rinne. Love for romantic partners, friends, strangers, pets and nature were also part of the study, which was published this week in the Cerebral Cortex journal, Oxford University Press.

According to the research, brain activity is influenced not only by the closeness of the object of love, but also by whether it is a human being, another species or nature.

Unsurprisingly, compassionate love for strangers was less rewarding and caused less brain activation than love in close relationships. Meanwhile, love of nature activated the reward system and visual areas of the brain, but not the social brain areas.

Pet-owners identifiable by brain activity

The biggest surprise for the researchers was that the brain areas associated with love between people ended up being very similar, with differences lying primarily in the intensity of activation. All types of interpersonal love activated areas of the brain associated with social cognition, in contrast to love for pets or nature — with one exception.

Subjects’ brain responses to a statement like the following, on average, revealed whether or not they shared their life with a furry friend:

‘You are home lolling on the couch and your pet cat pads over to you. The cat curls up next to you and purrs sleepily. You love your pet.’

‘When looking at love for pets and the brain activity associated with it, brain areas associated with sociality statistically reveal whether or not the person is a pet owner. When it comes to the pet owners, these areas are more activated than with non-pet owners,’ says Rinne.

Love activations were controlled for in the study with neutral stories in which very little happened. For example, looking out the bus window or absent-mindedly brushing your teeth. After hearing a professional actor’s rendition of each “love story”, participants were asked to imagine each emotion for ten seconds.

This is not the first effort at finding love for Rinne and his team, which includes researchers Juha Lahnakoski, Heini Saarimäki, Mikke Tavast, Mikko Sams and Linda Henriksson. They have undertaken several studies seeking to deepen our scientific knowledge of human emotions. The group released research mapping subjects’ bodily experiences of love a year ago, with the earlier study also linking the strongest physical experiences of love with close interpersonal relationships.

Not only can understanding the neural mechanisms of love help guide philosophical discussions about the nature of love, consciousness, and human connection, but also, the researchers hope that their work will enhance mental health interventions in conditions like attachment disorders, depression or relationship issues.

More on the previous research here: https://www.aalto.fi/en/news/where-do-we-feel-love

END

Finding love: Study reveals where love lives in the brain

Researchers have taken looking for love to a whole new level, revealing that different types of love light up different parts of the brain

2024-08-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers develop high-entropy non-covalent cyclic peptide glass

2024-08-26

Researchers from the Institute of Process Engineering (IPE) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences have developed a sustainable, biodegradable, biorecyclable material: high-entropy non-covalent cyclic peptide (HECP) glass. This innovative glass features enhanced crystallization-resistance, improved mechanical properties, and increased enzyme tolerance, laying the foundation for its application in pharmaceutical formulations and smart functional materials. This study was published in Nature Nanotechnology on ...

Mapping the sex life of Malaria parasites at single cell resolution, reveals the genetics underlying Malaria transmission

2024-08-26

Malaria is caused by a eukaryotic microbe of the Plasmodium genus, and is responsible for more deaths than all other parasitic diseases combined. In order to transmit from the human host to the mosquito vector, the parasite has to differentiate to its sexual stage, referred to as the gametocyte stage. Unlike primary sex determination in mammals, which occurs at the chromosome level, it is not known what causes this unicellular parasite to form males and females. New research at Stockholm University has implemented high-resolution genomic tools to map the global repertoire of genes ...

Communicating consensus strengthens beliefs about climate change

2024-08-26

Climate scientists have long agreed that humans are largely responsible for climate change. However, people often do not realize how many scientists share this view. A new 27-country study published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour finds that communicating the consensus among scientists can clear up misperceptions and strengthen beliefs about climate change.

The study is co-led by Bojana Većkalov at the University of Amsterdam and Sandra Geiger of the University of Vienna. Kai Ruggeri, professor of health policy and management at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, is the corresponding author.

Scientific consensus identifying humans as primarily ...

Almost half of FDA-approved AI medical devices are not trained on real patient data

2024-08-26

Artificial intelligence (AI) has practically limitless applications in healthcare, ranging from auto-drafting patient messages in MyChart to optimizing organ transplantation and improving tumor removal accuracy. Despite their potential benefit to doctors and patients alike, these tools have been met with skepticism because of patient privacy concerns, the possibility of bias, and device accuracy.

In response to the rapidly evolving use and approval of AI medical devices in healthcare, a multi-institutional team of researchers at the UNC School of Medicine, Duke University, Ally Bank, Oxford University, Colombia University, and University of Miami have been on a mission to build ...

Does the extent of structural racism in a neighborhood affect residents’ risk of cancer from traffic-related air pollution?

2024-08-26

High levels of traffic-related air pollutants have been linked with elevated risks of developing cancer and other diseases. New research indicates that multiple aspects of structural racism—the ways in which societal laws, policies, and practices systematically disadvantage certain racial or ethnic groups—may contribute to increased exposure to carcinogenic traffic-related air pollution. The findings are published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

Most studies suggesting that structural racism, which encompasses factors such as residential segregation and differences in economic status and homeownership, may influence ...

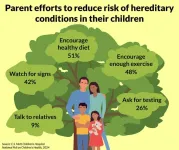

2 in 3 parents want help preventing their child from developing hereditary health conditions

2024-08-26

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – Among things many families don’t wish to pass down to their children and grandchildren: medical issues.

One in five parents say their child has been diagnosed with a hereditary condition, while nearly half expressed concerns about their child potentially developing such a condition, a new national poll suggests.

And two thirds of parents want their healthcare provider to suggest ways to prevent their child from developing a health problem that runs in the family, according to the University of Michigan Health C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National ...

Could psychedelic-assisted therapy change addiction treatment?

2024-08-26

by Amy Norton

PISCATAWAY, NJ – After years of being seen as dangerous “party drugs,” psychedelic substances are receiving renewed attention as therapies for addiction -- but far more research is needed, according to a new special series of articles in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, published at Rutgers University.

Psychedelics are substances that essentially alter users’ perceptions and thoughts about their surroundings and themselves. For millennia, indigenous cultures have used plants with psychedelic properties in traditional medicine and spiritual rituals. And for a time in the mid-20th ...

Sustaining oyster farming with sturdier rafts

2024-08-26

Amid the rising human population and pressure on food supplies, the world can’t be everyone’s oyster. But perhaps there might be more oysters to eat if an Osaka Metropolitan University-led research team’s findings mean sturdy plastic rafts will be used in their farming.

Conventional oyster farming uses bamboo rafts with additional flotation devices such as Styrofoam. Though relatively affordable, these rafts can be damaged in typhoons. The OMU-led researchers propose a polyethylene raft that keeps costs manageable but is about five times more durable than a bamboo raft.

OMU Graduate School of Engineering Associate ...

People of lower socioeconomic status less likely to receive cataract surgery in private clinics

2024-08-26

Despite increased funding for cataract surgeries to private, for-profit clinics, access to surgery fell 9% for lower-income people, according to new research published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) https://www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.240414.

“Unexpectedly, despite new public funding for operations provided in private for-profit surgical centres, which was intended to fully cover all overhead costs and remove the need to charge patients, this disparity did not decrease, but instead grew ...

Tick-borne Powassan virus in a child

2024-08-26

With tick-borne viruses such as Powassan virus increasing in Canada, clinicians should consider these infections in patients with encephalitis, as a case study shows in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) https://www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.240227.

Although rare, Powassan virus is serious, with a death rate of 10%–15% in people with encephalitis, and it can cause lingering health effects after infection. The virus can transmit within 15 minutes of tick attachment, and symptoms can develop 1–5 weeks later.

In this case study, a 9-year-old child with up-to-date vaccinations ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Do prostate cancer drugs interact with certain anticoagulants to increase bleeding and clotting risks?

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

[Press-News.org] Finding love: Study reveals where love lives in the brainResearchers have taken looking for love to a whole new level, revealing that different types of love light up different parts of the brain