(Press-News.org) PULLMAN, Wash. -- A computer algorithm can efficiently find genetic mutations that work together to drive cancer as well as other important genetic clues that researchers might someday use to develop new treatments for a variety of cancers.

Reporting in the journal Frontiers in Bioinformatics, a Washington State University-led team used a novel network computer model to find co-occurring mutations as well as other similarities among DNA sequence elements across several types of cancer. The model allows for easier searches for patterns in huge seas of cancer genetic data.

“This is a study not of one particular cancer, where you dive in and try to understand it, but rather of many cancers together, looking for patterns and things that could someday be used for drug discovery,” said corresponding author Assefaw Gebremedhin, associate professor in the WSU School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

Cancer tends to be talked about as one disease, but it’s really a spectrum of diseases where different driver mutations dictate the disease’s progression and prognosis, said co-author and University of Vermont molecular genetics researcher Steven Roberts. A better understanding of how common the different mutations and driver genes are across different types of cancer could help to prioritize possible targets for treatment. But cancer researchers have been stymied in their search for clues by the huge amount of computation required to study long genetic sequences and a large number of mutations.

“We couldn’t really look at all of the sequences because the computational space would be too large,” said Roberts. “If you try to take all the genomic data together and analyze all of it, the mathematical problem scales exponentially, and you just overwhelm the system.”

The network model developed by the WSU team, which is called DiWANN, is sparser and more efficient than existing network models without losing key structural components.

“This model gets to the minimal way to represent things without losing information,” said Gebremedhin. “Our model tries to understand relationships between sequences in a more effective way, and by effective, I mean they can be computed quickly. With this minimal representation of the network, you can get more information and make computation scalable.”

Since developing their DiWANN model five years ago, the researchers have used it to look at the geographic distribution of tick-borne diseases as well as the spread of COVID-19 during the pandemic.

In this work, the researchers added a data reduction step to further reduce the amount of required computation and a second computer model to gain further insights into co-occurring genes. WSU computer science Ph.D. student Shruti Patil led this effort and is the first author of the study.

The researchers found evidence in their work, for instance, that two mutations in pancreatic cancer nearly always show up together -- something that had only been suspected. One of the mutations, tumor protein 53, suppresses tumor growth while the other, known as KRAS, is a driver of proliferation.

The researchers identified cancer types that are closely connected to each other and that could perhaps be susceptible to common drug treatments. Some cancers were homogenous, meaning they all had similar mutations that lead to cancer, whereas other types of cancers had a huge variety of different mutations.

“Some of the certain cancer types are very, very homogenous, and their driver mutations were almost always the same, but then you get some other cancer types where it’s all over the map,” said Roberts. “Those are the ones, based on our predictions, that are probably going to be the hardest to treat.”

Because it provides sparse information, the WSU network model allows the researchers to expand the number of tumors that they can study.

“This increases our power to actually detect novel interactions and novel aspects of how these tumors behave,” said Roberts. “If we can actually screen through large data sets, it’s a much faster way to go about it.”

The researchers are now working to develop a web-based tool for public health experts, so that researchers in health can more easily use the model to study complex questions in cancer and other diseases. The work was supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Cancer Institute.

END

Researchers improve search for cancer drivers

2024-09-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Mirror, mirror, in my tank, who’s the biggest fish of all?

2024-09-11

What if that proverbial man in the mirror was a fish? Would it change its ways? According to an Osaka Metropolitan University-led research group, yes, it would.

In what the researchers say in Scientific Reports is the first time for a non-human animal to be demonstrated to possess some mental states (e.g., mental body image, standards, intentions, goals), which are elements of private self-awareness, bluestreak cleaner wrasse (Labroides dimidiatus) checked their body size in a mirror before choosing whether to attack fish that were slightly larger or smaller than themselves.

The ...

Scripps Research scientists expand the genetic alphabet to create new proteins

2024-09-11

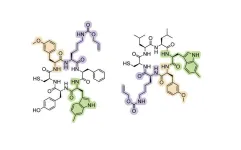

LA JOLLA, CA—It’s a dogma taught in every introductory biology class: Proteins are composed of combinations of 20 different amino acids, arranged into diverse sequences like words. But researchers trying to engineer biologic molecules with new functions have long felt limited by those 20 basic building blocks and strived to develop ways of putting new building blocks—called non-canonical amino acids—into their proteins.

Now, scientists at Scripps Research have designed a new paradigm for easily adding non-canonical amino acids to proteins. Their approach, described in Nature Biotechnology on September 11, 2024, revolves around using ...

Breakthrough research sheds light on the hidden effects of stress on sperm

2024-09-11

A groundbreaking study led by researchers at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus reveals that stress-induced changes in sperm motility occur after a stressful event, rather than during it and improves sperm performance. The discovery is essential in understanding how stress impacts the reproductive process to improve fetal development outcomes.

The study was published today in Nature Communications.

Over the last five decades, there has been a notable decline in semen quality, which has coincided with environmental stressors. This new research identifies how stress affects the ability of ...

Throat problems could impair autonomic nervous system's ability to regulate blood pressure

2024-09-11

Throat problems could impair autonomic nervous system's ability to regulate blood pressure

Research suggests problems at junction between air and food passages may ‘overwhelm’ the Vagus nerve

Patients with throat problems were less able to regulate their blood pressure in a new study led by the University of Southampton.

The study published in JAMA Otolaryngology is the first to observe reduced baroreflex sensitivity in patients with throat symptoms.

The baroreflex is a crucial part of the autonomic nervous system which detects changes ...

Pandemic of homicide grief in global Black communities urgently needs a public health response

2024-09-11

The Centre for Research and Innovation for Black Survivors of Homicide Victims (The CRIB) is calling for decisive action to address the grief from homicide that is disproportionately affecting Black communities worldwide — and to tackle the root causes of homicide that impact this population.

In a paper published in the journal Homicide Studies, University of Toronto social work professor Tanya Sharpe and colleagues argue that the prevalence and spread of homicide grief — the grief that follows the ...

How do human and dog interactions affect the brain?

2024-09-11

During social interactions, the activity of the brain’s neurons becomes synchronized between the individuals involved. New research published in Advanced Science reveals that such synchronization occurs between humans and dogs, with mutual gazing causing synchronization in the brain’s frontal region and petting causing synchronization in the parietal region. Both regions are associated with attention.

The strength of this synchronization increased with growing familiarity of human–dog pairs over 5 days, and tests indicated that the human is the leader while ...

Can green finance effectively reduce carbon dioxide emissions while promoting economic growth?

2024-09-11

New research published in Business Strategy and the Environment based on information from G7 countries demonstrates that green finance—loans, investments, and incentives that support environmentally-friendly projects and activities—can reduce carbon dioxide emissions. Also, data indicate that investments in green projects are profitable.

The study found that G7 countries' environmental conditions have been negatively impacted by economic development; however, there are advantages of green finance solutions for economic growth.

The study’s investigators ...

Are there racial differences in the use of opioids after returning home from hospitalizations for hip fractures?

2024-09-11

In an analysis of information on 164,170 older adult Medicare beneficiaries who were hospitalized for hip fractures, a similar proportion of Black and white beneficiaries used opioids after they were discharged and returned to the community, but Black beneficiaries consistently received lower doses of the pain medications.

In the study published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, investigators observed that on average Black beneficiaries received the equivalent of around 250 fewer milligrams ...

Are long stems on flowers an adaptation that encourages bat pollination?

2024-09-11

Flowers that are pollinated by bats tend to have long stems that make them stand out from the surrounding foliage. New research published in New Phytologist reveals the evolutionary advantage that this characteristic provides to plants to ensure that they are discovered by bats.

In simple backgrounds lacking foliage, bats showed no significant difference in the time it took them to find flowers with long versus short stems, but in complex backgrounds (with arrays of leaves and flowers), bats took nearly twice as much time to locate short-stemmed flowers.

Investigators hypothesize that flowers located away from the surrounding foliage likely help bats to distinguish ...

New research provides insights into how the brain regenerates lost myelin

2024-09-11

The neurons of the brain are protected by an insulating layer called myelin. In certain diseases like multiple sclerosis, this protective layer is damaged and lost, leading to death of neurons and disability. New research published in The FEBS Journal reveals the importance of a protein called C1QL1 for promoting the replacement of the specialized cells that produce myelin. The findings could have important implications for the ongoing effort to develop new and improved therapies for the treatment of demyelinating diseases.

In experiments conducted in mice, deleting the gene that codes for C1QL1 caused a delay in the rate at which oligodendrocytes ...