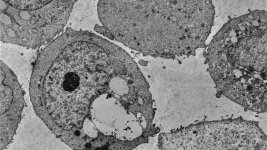

(Press-News.org) Even at concentrations too low to kill, exposure to widely used agrochemicals – pesticides, herbicides, and fungicides, among others – has pervasive negative impacts on insect behavior and physiology, researchers report. The findings highlight the need for more comprehensive pesticide assessments, focusing not just on lethality but also on unintended long-term ecological harm to safeguard biodiversity. Over the past decade, many reports have highlighted alarming declines in insect biodiversity worldwide, likely driven by habitat loss from farming and urbanization, climate change, and extensive pesticide use. Sublethal doses of pesticides – concentrations too low to kill – have emerged as a significant yet underexplored factor in this decline. Previous research has demonstrated how sublethal doses of agricultural chemicals can disrupt various aspects of insect biology, including metabolism, development, reproduction, immunity, and behavior. However, safety assessments of these chemicals often focus on lethal doses, and systemic experimental studies on the subtle, chronic effects of sublethal doses on non-target species remain lacking. To address this knowledge gap, Lautaro Gandara and colleagues developed a high-throughput platform using Drosophila melanogaster – a well-established insect model for toxicological assessments – to evaluate the physiological, behavioral, and fitness impacts of sublethal exposure to a suite of agrochemical molecules. Gandara et al. used a chemical library of 1,024 different agrochemicals and found that 57% of these chemicals – many without known insect-specific actions – significantly disrupted larval behavior. In addition to behavioral changes, the authors identified widespread alterations in the proteins that have phosphate groups attached to them, indicating deeper physiological impacts. Tests with chemical combinations at sublethal concentrations found widely in natural habitats were also shown to reduce D. melanogaster developmental speed and reproductive output and to compromise long-term survivability. What’s more, the findings revealed that slightly elevated environmental temperatures amplified pesticide toxicity, highlighting potential risks under warming environmental conditions. Gandara et al. also found that similar behavioral disruptions were observed in other species exposed to sublethal doses, including mosquitos and butterflies, suggesting broader ecological implications.

END

Sublethal agrochemical exposure disrupts insect behavior and long-term survivability

Summary author: Walter Beckwith

2024-10-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Understanding that US wildfires are becoming faster-moving is key to preparedness

2024-10-24

“The modern era of megafires is often defined based on wildfire size,” say Jennifer Balch and colleagues in a new study, “but it should be defined based on how fast fires grow and their consequent societal impacts.” Balch and colleagues report that wildfire growth rates in the U.S. have surged over 250% over the last 2 decades. Although these fast-moving infernos, or “fast fires” – those spreading more than 1,620 hectares in a day – account for only 2.7% of wildfire events from 2001 to 2020, researchers report that they are responsible for 89% of the total structures damaged ...

Model predicts PFAS occurrence in groundwater in the US

2024-10-24

According to a new machine learning-assisted predictive model, as many as 95 million Americans may rely on groundwater containing PFAS for their drinking water supplies before any treatment, researchers report. This raises concerns about unmonitored contamination in domestic and public water supplies. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), often called “forever chemicals,“ are highly persistent environmental contaminants linked to adverse environmental and health effects. Used in many consumer products, these organic pollutants have become ubiquitous in the environment and ...

By studying new species of tardigrade, researchers glean insights into radiation tolerance

2024-10-24

Tardigrades, eight-legged microorganisms colloquially known as “water bears,” are the most radiation-tolerant animals on Earth. Now, by studying a newly identified species of tardigrade, researchers have gleaned valuable insights into the animal’s ability to withstand radiation. These findings hold implications for safeguarding human health in extreme environments, such as spaceflight. Roughly 1,500 species of tardigrades have been described. These creatures can endure gamma radiation ...

Plastic chemical causes causes DNA breakage and chromosome defects in sex cells

2024-10-24

A new study conducted in roundworms finds that a common plastic ingredient causes breaks in DNA strands, resulting in egg cells with the wrong number of chromosomes. Monica Colaiácovo of Harvard Medical School led the study, which was published October 24 in the journal PLOS Genetics.

Benzyl butyl phthalate (BBP) is a chemical that makes plastic more flexible and durable, and is found in many consumer products, including food packaging, personal care products and children’s toys. Previous studies have shown that BBP interferes with ...

Vitamin K supplement slows prostate cancer in mice

2024-10-24

Prostate cancer is a quiet killer. In most men, it’s treatable. However, in some cases, it resists all known therapies and turns extremely deadly. A new discovery at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) points to a potentially groundbreaking solution. CSHL Professor Lloyd Trotman’s lab has found that the pro-oxidant supplement menadione slows prostate cancer progression in mice. The supplement is a precursor to vitamin K, commonly found in leafy greens. The story begins more than two decades ago.

In 2001, the National Cancer Institute’s SELECT trial sought to determine if an antioxidant ...

Wildfires are becoming faster and more dangerous in the Western U.S.

2024-10-24

Fast-growing fires were responsible for nearly 90 percent of fire-related damages despite being relatively rare in the United States between 2001-2020, according to a new study led by the University of Colorado Boulder. “Fast fires,” which thrust embers into the air ahead of rapidly advancing flames, can ignite homes before emergency responders are able to intervene. The work, published today in Science, shows these fires are getting faster in the Western U.S., increasing the risk for millions of people.

The research highlights a critical gap in hazard preparedness across the U.S. — National-level ...

Gut bacteria transfer genes to disable weapons of their competitors

2024-10-24

Bacteria evolve rapidly in the human gut by sharing genetic elements with each other. Bacteriodales is a prolific order of gut bacteria that trade hundreds of genetic elements. Little is known, however, about the effects of these DNA transfers, either to the fitness of the bacteria or the host.

New research from the University of Chicago shows that a large, ubiquitous mobile genetic element changes the antagonistic weaponry of Bacteroides fragilis, a common bacterium of the human gut. Acquisition of this element shuts down a potent weapon ...

A new hydrogel semiconductor represents a breakthrough for tissue-interfaced bioelectronics

2024-10-24

The ideal material for interfacing electronics with living tissue is soft, stretchable, and just as water-loving as the tissue itself—in short, a hydrogel. Semiconductors, the key materials for bioelectronics such as pacemakers, biosensors, and drug delivery devices, on the other hand, are rigid, brittle, and water-hating, impossible to dissolve in the way hydrogels have traditionally been built.

A paper published today in Science from the UChicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (PME) has solved this challenge that has long ...

Bird study finds sons help their parents less than daughters because they’re scouting future prospects

2024-10-24

Male birds help their parents less than females because they’re too busy scouting for new places to live and breed, a remarkable new study shows.

The study, led by researchers at the Centre for Ecology and Conservation at the University of Exeter, examined the cooperative behaviour and movement patterns of social birds called white-browed sparrow weavers, which live in the Kalahari desert.

These birds live in family groups in which only a dominant pair breeds – and their grown-up offspring, particularly females, help ...

Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine (WFIRM) awarded up to $48 million to utilize body-on-a-chip technologies to study fibrosis-inducing chemical injuries

2024-10-24

The Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine (WFIRM) has been awarded an eight-year contract, valued up to $48 million from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to support the utilization of cutting-edge body-on-a-chip technologies aimed at studying and developing potential treatments for sulfur mustard and other fibrosis-inducing chemicals. The program has been approved with an initial contracting commitment of approximately $18 million.

This contract represents a continued partnership between WFIRM and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Father’s tobacco use may raise children’s diabetes risk

Structured exercise programs may help combat “chemo brain” according to new study in JNCCN

The ‘croak’ conundrum: Parasites complicate love signals in frogs

Global trends in the integration of traditional and modern medicine: challenges and opportunities

Medicinal plants with anti-entamoeba histolytica activity: phytochemistry, efficacy, and clinical potential

What a releaf: Tomatoes, carrots and lettuce store pharmaceutical byproducts in their leaves

Evaluating the effects of hypnotics for insomnia in obstructive sleep apnea

A new reagent makes living brains transparent for deeper, non-invasive imaging

Smaller insects more likely to escape fish mouths

Failed experiment by Cambridge scientists leads to surprise drug development breakthrough

Salad packs a healthy punch to meet a growing Vitamin B12 need

Capsule technology opens new window into individual cells

We are not alone: Our Sun escaped together with stellar “twins” from galaxy center

Scientists find new way of measuring activity of cell editors that fuel cancer

Teens using AI meal plans could be eating too few calories — equivalent to skipping a meal

Inconsistent labeling and high doses found in delta-8 THC products: JSAD study

Bringing diabetes treatment into focus

Iowa-led research team names, describes new crocodile that hunted iconic Lucy’s species

One-third of Americans making financial trade-offs to pay for healthcare

Researchers clarify how ketogenic diets treat epilepsy, guiding future therapy development

PsyMetRiC – a new tool to predict physical health risks in young people with psychosis

Island birds reveal surprising link between immunity and gut bacteria

Research presented at international urology conference in London shows how far prostate cancer screening has come

Further evidence of developmental risks linked to epilepsy drugs in pregnancy

Cosmetic procedures need tighter regulation to reduce harm, argue experts

How chaos theory could turn every NHS scan into its own fortress

Vaccine gaps rooted in structural forces, not just personal choices: SFU study

Safer blood clot treatment with apixaban than with rivaroxaban, according to large venous thrombosis trial

Turning herbal waste into a powerful tool for cleaning heavy metal pollution

Immune ‘peacekeepers’ teach the body which foods are safe to eat

[Press-News.org] Sublethal agrochemical exposure disrupts insect behavior and long-term survivabilitySummary author: Walter Beckwith