(Press-News.org) Ever had an itchy nose or, worse, an unreachable spot on your back that drives you mad? Now imagine an itch that refuses to go away, no matter how hard or long you scratch. That persistent itch, or pruritus, may actually be one of the skin’s first lines of defense against harmful invaders, according to neuroimmunologist Juan Inclan-Rico of the University of Pennsylvania.

“It’s inconvenient, it’s annoying, but sensations like pain and itch are crucial. They’re ever-present, especially when it comes to skin infections,” says Inclan-Rico, a postdoctoral researcher in the Herbert Lab at Penn’s School of Veterinary Medicine, who has been exploring what he calls “sensory immunity,” the idea that “if you can feel it, you can react to it.” Itch, he explains, is the body’s way of detecting threats such as skin infections before they can take hold.

But in a recent paper published in Nature Immunology, De’Broski Herbert, professor of pathobiology at Penn Vet, and his team flipped that theory on its head. They shed light on how a parasitic worm, Schistosoma mansoni, can sneak into the human body by evading this very defense mechanism, bypassing the itch response entirely. And while there are prophylactic therapeutics for those who may encounter S. mansoni, options for treating someone who has unknowingly been exposed are relatively scant, and these research findings pave the way for addressing this concern.

“These blood flukes, which are among the most prevalent parasites in humans, infecting nearly 250 million people, have seemingly evolved to block the itch, making it easier for them to enter the body undetected,” Inclan says. “So, we wanted to figure out how they do it. What are the molecular mechanisms underlying how they turn off such an essential sensory alarm? And what can this teach us about the sensory apparatus that drives us to scratch a pesky itch?”

Not all reactions are equal

Inclan-Rico says that the research really began when his project revealed that certain strains of mice were more susceptible to infection of S. mansoni. “Specifically, some of the mice had a higher number of parasites successfully traversing throughout body following skin penetration.”

Heather Rossi, a senior research investigator in the Herbert lab and co-author on the study, says that this motivated the team to investigate the neuronal activity at play, with special attention paid to MrgprA3 neurons, which are commonly associated with immunity and itchiness.

They then looked at how a “cousin” of S. mansoni that’s typically found in avian species but has been shown to cause swimmer’s itch in humans, and they found a stark difference between the reaction or lack of it within the mice.

“While avian schistosomes triggered a strong itch response in the skin, S. mansoni was unable to induce this reaction,” Rossi says. “What’s more, when we introduced chloroquine—an anti-malarial drug that’s known to cause pruritus by interacting with MrgprA3—to the mice treated with S. mansoni antigens, we found that itching was blocked almost entirely.”

A closer look

To further investigate the biochemistry involved in S. mansoni’s workaround for skating past MrgprA3 neurons, the researchers employed a three-legged strategy: Using light to genetically activate neurons on ear skin prior to infection, administering chloroquine, and genetically reducing the population of MrgprA3 neurons in the mice.

“Turns out that activating these neurons blocks the entry,” Inclan-Rico says. “It creates an inflammatory environment, we think, within the skin that prevents the entry and dissemination of the parasites, which is particularly cool.”

Members of the Herbert lab, (Left to right): Ulrich Femoe, Heather Rossi, Adriana Stephenson, Evonne Jean, Annabel Ferguson, De'Broski Herbert, Juan Inclan Rico, Heidi Winters, Camila Napuri, Li-Yin Hung, Olufemi Akinkuotu. (Credit: Adriana Stephenson)

The Herbert lab has been studying parasites that enter the skin, migrate through the layers of connective tissue all the way through until they find a blood vessel, and chart a course towards the lung. There they molt into another larval stage and then use the liver and portal vein to make their way to the intestines as adults where they lay eggs, leading to characteristic symptoms in humans like abdominal swelling, fever, and pain.

“So, as you may imagine, if there are fewer parasites entering the body during initial infection, and also fewer parasites making their way into the lungs,” Inclan-Rico says. “This suggests two things: That the activation of these neurons is blocking the entry of the parasites and it’s also inhibiting their dissemination through the body.” The researchers also found that the mice that had MrgprA3 ablation saw an increased amount of lung parasite infection.

Subcellular crosstalk

Armed with the knowledge that MrgprA3 neurons were involved in blocking the parasites, the team hypothesized that there may be crosstalk between these cells and immune cells, so they began investigating the relationship between these two classes.

“When we activated MrgprA3, it increased the number of macrophages in the skin,” Inclan-Rico says. “These are the white blood cells that typically come in and gobble up infectious elements, and so, when we depleted the macrophages, we saw that this was in fact a causal relationship, that the neurons were functionally linked to the macrophage response because without them the worm infection wasn’t blocked at all.”

Next, the Herbert team sought to find the specific signaling molecules involved and discovered that downstream of MrgprA3 activation the neuropeptide CGRP was released, demonstrating that this neuropeptide plays a key role in neuron-immune cell communication.

“CGRP acts like a messenger between neurons and macrophages,” Inclan-Rico says, “and this signaling triggers the activation of immune cells at the site of infection, which helps contain the parasite.”

However, CGRP wasn’t acting alone as the team found that the nuclear protein IL-33, typically known as an alarm signal released by damaged cells, played a surprising, significant role. When they examined macrophages, they discovered that IL-33 was not just being reduced but was instead acting within the cell nucleus.

“Up until now, people just thought that IL-33 was a nuclear protein, but we didn’t know exactly what it was doing in there. Its role was more thought to be as a secreted factor, either as a consequence of cell death or potentially from immune cells secreting it directly,” Rossi says. “But we did a number of experiments to prove that, in fact, IL-33 in macrophages controls the accessibility of DNA, essentially opening DNA’s tight packaging material and allowing pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF to be expressed.”

This pro-inflammatory environment is critical for forming a protective barrier that prevents the parasite from advancing farther into the body.

“It’s a two-step process,” Inclan-Rico says. “First, MrgprA3 neurons release CGRP, which signals into macrophages. Then, IL-33 held within the macrophages’ nuclei is greatly reduced, which enhances the inflammatory response and helps block the parasite’s entry.”

Interestingly, they also found that when IL-33 was genetically deleted from macrophages, the protective response induced by itchy neurons was lost.

“This tells us that the neurons are orchestrating this whole defense, but they need the macrophages—and specifically IL-33 in those macrophages—to mount a full immune response,” Herbert says.

Looking ahead, the Herbert lab plans to dive deeper into understanding the mechanisms behind this neuron-immune communication.

“We’re really interested in identifying the molecules that parasites use to suppress the neurons and whether we can harness that knowledge to block parasite entry more effectively,” Herbert says. They also hope to identify other molecules, beyond CGRP and IL-33, that are involved in this signaling pathway.

“If we can pinpoint the exact components that parasites are targeting to evade the itch response, we could develop new therapeutic approaches that not only treat parasitic infections but potentially offer relief for other itch-related conditions like eczema or psoriasis,” Herbert says.

De’Broski R. Herbert is the presidential professor of immunology and a professor of pathobiology at the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Juan Manuel Inclan-Rico is a postdoctoral researcher in the Herbert Lab at Penn Vet.

Heather L. Rossi is a senior research investigator in the Herbert Lab at Penn Vet.

Other researchers are Ulrich M. Femoe, Annabel A. Ferguson, Bruce D. Freedman Li-Yin Hung, Xiaohong Liu, Fungai Musaigwa, Camila M. Napuri, Christopher F. Pastore, and Adriana Stephenson of Penn Vet; Wenqin Luo and Qinxue Wu of the Perelman School of Medicine at Penn; Cailu Lin and Danielle R. Reed of the Monell Chemical Senses Center; Petr Horák and Tomáš Macháček of Charles University, Czech Republic; and Ishmail Abdus-Saboor of Columbia University.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants T32 AI007532-24, R01 AI164715-01, U01 AI163062-01, P30-AR069589, and R01 AI123173-05 and contract HHSN272201700014I), Charles University (Cooperatio Biology, UNCE24/SCI/011, SVV 260687), and the Czech Science Foundation (GA24-11031S).

END

Scientific discovery scratching beneath the surface of itchiness

A collaborative study led by researchers from Penn Vet provides insights into how a species of worms found a way to evade the mammalian urge to scratch an itch

2024-10-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

SFSU psychologists develop tool to assess narcissism in job candidates

2024-10-25

It feels like narcissism is everywhere these days: politics, movies and TV, sports, social media. You might even see signs of it at work, where it can be particularly detrimental. Is it possible to keep a workplace free of destructive, manipulative egotists?

More and more organizations have come to San Francisco State University’s experts in organizational psychology asking for help doing just that. In response, University researchers developed a tool for job interviews to assess narcissistic grandiosity among potential job candidates. San Francisco State Psychology Professors Kevin Eschleman and Chris ...

Invisible anatomy in the fruit fly uterus

2024-10-25

You have likely not spent much time thinking about the uterus of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. But then, neither have most scientists, even though Drosophila is one of the most thoroughly studied lab animals. Now a team of biologists at the University of California, Davis, has taken the first deep look at the Drosophila uterus and found some surprises, which could have implications not just for understanding insect reproduction and potentially, pest control, but also for understanding fertility in humans.

The work is published Oct. 25 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Drosophila have been a favorite subject for ...

Skeletal muscle health amid growing use of weight loss medications

2024-10-25

A recent commentary published in The Lancet journal highlights the critical importance of skeletal muscle mass in the context of medically induced weight loss, particularly with the widespread use of GLP-1 receptor agonists. These medications, celebrated for their effectiveness in treating obesity, have raised concerns regarding the potential for substantial muscle loss as part of the weight loss process.

Dr. Steven Heymsfield, professor of metabolism and body composition, and Dr. M. Cristina Gonzalez, adjunct and visiting professor in metabolism-body composition, both of Pennington Biomedical Research Center, joined colleagues Dr. Carla Prado of the University ...

The Urban Future Prize Competition awards top prizes to Faura and Helix Earth Technologies and highlights climate adaptation solutions with the inaugural Future Resilience Prize

2024-10-25

NYU Tandon School of Engineering's Urban Future Lab named the winners of its 2024 Future Resilience and Future Solutions prizes, at its 8th annual Urban Future Summit on October 24, 2024 at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in New York City. Through the generous support of The New York Community Trust, MUFG Bank, Mitsubishi Corporation (Americas), the Urban Future Lab continues to catalyze groundbreaking solutions for the climate crisis and this year, they’ve expanded their focus to include adaptation as a critical piece of the puzzle.

After an afternoon of pitches, the jury, comprised of industry experts and ...

Wayne State researcher secures two grants from the National Institute on Aging to address Alzheimer’s disease

2024-10-25

DETROIT – A Wayne State University School of Medicine faculty member has been awarded a total of $2.3 million by the National Institute on Aging of the National institutes of Health for two new, concurrent projects that both address questions related to Alzheimer’s disease, a progressive, age-related degenerative brain disease characterized by memory problems, impaired judgment, cognitive issues and changes in personality.

Joongkyu Park, Ph.D., assistant professor of pharmacology and of neurology, is the principal investigator on “Local protein synthesis ...

NFL’s Bears add lifesavers to the chain of survival in Chicago

2024-10-25

CHICAGO, October 22, 2024— The American Heart Association and the Chicago Bears brought cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and automated external defibrillator (AED) training to the Illinois High School Association (IHSA) Girls Flag Football State Finals on Saturday, Oct. 19. More than 150 youth athletes, coaches and league administrators learned lifesaving skills building their confidence and capabilities to respond in the event of a cardiac emergency. According to American Heart Association data, 9 out of every 10 people who experience cardiac arrest outside of a hospital die, in part ...

High-impact clinical trials generate promising results for improving kidney health: Part 1

2024-10-25

The results of numerous high-impact phase 3 clinical trials that could affect kidney-related medical care will be presented in-person at ASN Kidney Week 2024 October 23–27.

Finerenone—a selective non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist—has been shown to have kidney protective effects in individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) with type 2 diabetes, but its effects on kidney outcomes in patients with heart failure with and without diabetes and/or CKD are not known. To investigate, researchers analyzed data from 6,001 participants enrolled in the FINEARTS-HF trial, a global, randomized ...

Early, individualized recommendations for hospitalized patients with acute kidney injury

2024-10-25

About The Study: Among patients hospitalized with acute kidney injury, recommendations from a kidney action team did not significantly reduce the composite outcome of worsening acute kidney injury stage, dialysis, or mortality, despite a higher rate of recommendation implementation in the intervention group than in the usual care group.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, F. Perry Wilson, MD, email francis.p.wilson@yale.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2024.22718)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article ...

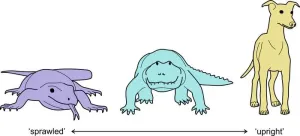

How mammals got their stride

2024-10-25

Mammals, including humans, stand out with their distinctively upright posture, a key trait that fueled their spectacular evolutionary success. Yet, the earliest known ancestors of modern mammals more resembled reptiles, with limbs stuck out to their sides in a sprawled posture.

The shift from a sprawled stance, like that of lizards, to the upright posture of modern mammals, as in humans, dogs, and horses, marked a pivotal moment in evolution. It involved a major reorganization of limb ...

Cancer risk linked to p53 in ulcerative colitis

2024-10-25

Researchers in the lab of Michael Sigal at the Max Delbrück Center and Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin have elucidated the role of the p53 gene in ulcerative colitis. The study, published in Science Advances, suggests a potential new drug target to stop disease progression to cancer.

A team of researchers led by Kimberly Hartl, a graduate student at the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology of the Max Delbrück Center (MDC-BIMSB) and Charité – Universitätsmedizin, have shed new light on the role of the p53 tumor suppressor gene ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New knowledge on heritability paves the way for better treatment of people with chronic inflammatory bowel disease

Under the Lens: Microbiologists Nicola Holden and Gil Domingue weigh in on the raw milk debate

Science reveals why you can’t resist a snack – even when you’re full

Kidney cancer study finds belzutifan plus pembrolizumab post-surgery helps patients at high risk for relapse stay cancer-free longer

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

[Press-News.org] Scientific discovery scratching beneath the surface of itchinessA collaborative study led by researchers from Penn Vet provides insights into how a species of worms found a way to evade the mammalian urge to scratch an itch