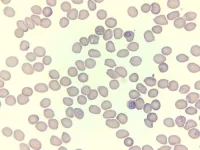

(Press-News.org) Malaria kills over 600,000 people a year, and as the climate warms, the potential range of the disease is growing. While some drugs can effectively prevent and treat malaria, resistance to those drugs is also on the rise.

New research from University of Utah Health has identified a promising target for new antimalarial drugs: a protein called DMT1, which allows single-celled malaria parasites to use iron, which is critical for parasites to survive and reproduce.

The results suggest that medications that block DMT1 might be very effective against malaria.

The new results are published in PNAS.

An ironic mystery

Paul Sigala, PhD, associate professor of biochemistry in the Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine (SFESOM) at the University of Utah, knew that iron is essential for parasite survival. Without iron, parasites rapidly die. And getting that iron from the human red blood cells in which the parasites live and divide is no simple task.

“We still don't really understand how parasites acquire iron in the red blood cell, which is rather ironic given that it's the most iron rich cell in the human body,” says Sigala, who is the senior author on the paper.

Researchers knew that the malaria parasites had to harvest iron-rich hemoglobin from human blood cells, crack it open to get at the iron inside, and move the iron to the parts of the parasite that need it.

But the proteins involved were “a bit of a black hole,” says Kade Loveridge, a graduate researcher in biochemistry in SFESOM and the first author on the paper. Malaria parasites are so distinct from better-studied organisms that the scientists had little prior knowledge to go on. “They don't have a lot of the normal proteins that you would need to get iron and transport it.”

A key player

The researchers suspected that DMT1 might help malaria parasites use iron because it looks somewhat similar to genes involved in metal transport in other organisms.

Importantly, they found that DMT1 is absolutely critical for parasite survival. The researchers edited the malaria parasites’ genome so that they could turn off DMT1 protein production at will. When they turned DMT1 off, the parasites died before being able to infect more blood cells—an unusually rapid demise, even for the loss of an essential protein.

The parasites’ rapid death could be a consequence of the importance of iron transport in many processes, Sigala says. “Blocking [this protein] is expected to impair not just one or two key processes but nearly all aspects of parasite viability during blood-stage infection,” he says.

Sure enough, DMT1 is necessary specifically because it’s involved in iron transport, the team confirmed. When they turned DMT1 activity down but not totally off—like a light on a dimmer switch—the parasites could still survive, but their growth slowed down. Intriguingly, giving them lots of extra iron brought them back up to speed. The researchers believe that, when iron is abundant in the environment, the handful of remaining DMT1 proteins can transport it quickly enough for parasites to grow normally. When there’s no DMT1 whatsoever, it doesn’t matter how much iron is around—malaria parasites can’t use it and rapidly die.

A crack in the door

The researchers are hopeful that DMT1 could be an effective target for new antimalarial drugs, thanks to its moderate similarity to human iron transporters, Loveridge says. “It’s similar enough that we could identify it,” he says, “but different enough that it’s possible that you could design a parasite-specific inhibitor of this transporter that has minimal impacts on the human protein.”

The fact that the parasites die so quickly when DMT1 is turned off is promising; if a drug can be developed or identified that prevents DMT1 activity, it could be faster-acting than current options. The lab is currently testing existing iron transport inhibitors to see if they could work as antimalarial drugs.

Loveridge adds that whether or not their discovery leads to new drug development, it’ll make it easier for future scientists to uncover more information about how the parasite grows and how to stop it. “We’re kind of cracking the door,” he says. “I hope that other people can throw it wide open.”

###

These results were published as "Identification of a divalent metal transporter required for cellular iron metabolism in malaria parasites" in PNAS on October 28, 2024.

This research was supported by NIH grants R35GM133764 and T32TR004392, the Utah Center for Iron and Heme Disorders, and the American Heart Association.

END

Discovery of critical iron-transport protein in malaria parasites could lead to faster-acting medications

2024-10-28

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Risky choices: How US laws affect migrant children’s journeys to border

2024-10-28

U.S. immigration law and the legal categorizations it imposes on migrants shape the journeys of migrant children from Central America as they move through Mexico toward the southern U.S. border, according to a new Yale study.

In the study, sociologist Ángel Escamilla García documents the various hard decisions Central American youth are forced to make during their journeys to maximize their chances of not being deported once they reach the United States. Those choices include concealing sexual assaults, beatings, and other crimes ...

Scientists address risks to supply chain in a connected world

2024-10-28

RICHLAND, Wash.—Scientists are gathering at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory this week for a first-ever conference to consider ways to protect critical systems such as our electrical grid, water treatment plants and financial networks that are vulnerable in new ways.

The Cyber Supply Chain Risk Management Conference, known as CySCRM 2024, is being held on the PNNL campus Tuesday-Wednesday, Oct. 29-30.

It’s a new kind of science meeting, one that scientist Jess Smith and colleagues felt compelled to create as they eye a new kind of risk—a ...

Don’t skip colonoscopy for new blood-based colon cancer screening, study concludes

2024-10-28

Newly available blood tests to screen for colorectal cancer sound far more appealing than a standard colonoscopy. Instead of clearing your bowels and undergoing an invasive procedure, the tests require only a simple blood draw. But are the tests effective?

A study led by researchers at Stanford Medicine concluded that the new tests are ideal for people who shy away from other colorectal cancer screening. However, if too many people who would have undergone colonoscopies or stool-based tests switch to the blood tests, colorectal cancer death rates will rise. Because the more established colonoscopies and stool tests ...

Up to half of Medicare beneficiaries lack financial resources to pay for a single hospital stay

2024-10-28

Embargoed for release until 5:00 p.m. ET on Monday 28 October 2024

@Annalsofim

Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization they represent. ...

Chemicals produced by fires show potential to raise cancer risk

2024-10-28

Derek Urwin has a special stake in his work as a cancer control researcher. After undergraduate studies in applied mathematics at UCLA, he became a firefighter. His inspiration to launch a second career as a scientist was the loss of his brother, Isaac, who died of leukemia at only 33 despite no history of cancer in their family. Working with Anastassia Alexandrova, a professor of chemistry and biochemistry in the UCLA College, he earned his doctorate.

Urwin is now a UCLA adjunct professor of chemistry — and still a full-time firefighter with the Los Angeles County Fire Department. In a recent publication, his science shed new light on the chemical underpinnings of exposures ...

Penn Nursing awarded $3.2 million grant to improve firearm safety

2024-10-28

PHILADELPHIA (October 28, 2024) – The University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing (Penn Nursing) has been awarded a $3.2 million, 5-year grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) to scale out an evidence-based secure firearm storage intervention at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). Firearms are now the leading cause of death for U.S. children and teens, driving the largest spike in children’s mortality in more than 50 years. The study aims to keep children safer from firearm injury and mortality by promoting secure firearm storage.

The intervention, ...

Bird wings inspire new approach to flight safety

2024-10-28

Taking inspiration from bird feathers, Princeton engineers have found that adding rows of flaps to a remote-controlled aircraft’s wings improves flight performance and helps prevent stalling, a condition that can jeopardize a plane’s ability to stay aloft.

“These flaps can both help the plane avoid stall and make it easier to regain control when stall does occur,” said Aimy Wissa, assistant professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering and principal investigator of the study, published in the Proceedings ...

Global fleet of undersea robots reveal the phytoplankton hidden beneath the ocean's surface

2024-10-28

Marine phytoplankton are fundamental to Earth’s ecology and biogeochemistry. Our understanding of the large-scale dynamics of phytoplankton biomass has greatly benefited from, and is largely based on, satellite ocean color observations from which chlorophyll-a (Chla), a commonly used proxy for carbon biomass, can be estimated. However, ocean color satellites only measure a small portion of the surface ocean, meaning that subsurface phytoplankton biomass is not directly monitored. Chla is also an imperfect ...

Climate, dead zones and fish: Solving a 'wicked problem' in Lake Erie and beyond

2024-10-28

Images

There's a famous piece of advice from hockey, attributed to Wayne Gretzky, about how it's better to skate to where the puck is headed rather than where it is.

Research is now showing that regulations designed to protect Lake Erie's water quality are heeding the Great One's words when it comes to safeguarding the Great Lake's fisheries.

Specifically, the currently recommended limits on the flow of nutrients into Lake Erie from agriculture may be too restrictive for some species of fish. They are, however, suited to maintain healthy fisheries until the ...

Dinosaurs thrived after ice, not fire, says a new study of ancient volcanism

2024-10-28

201.6 million years ago, one of the Earth's five great mass extinctions took place, when three-quarters of all living species suddenly disappeared. The wipeout coincided with massive volcanic eruptions that split apart Pangaea, a giant continent then comprising almost all the planet's land. Millions of cubic miles of lava erupted over some 600,000 years, separating what are now the Americas, Europe and North Africa. It marked the end of the Triassic period and the beginning of the Jurassic, the period when dinosaurs arose to take the place of Triassic creatures and dominate the planet.

The exact mechanisms of the End Triassic Extinction have long been debated, ...