(Press-News.org) ITHACA, N.Y. – A popular new strategy for combatting misinformation doesn’t by itself help people distinguish truth from falsehood but improves when paired with reminders to focus on accuracy, finds new Cornell University-led research supported by Google.

Psychological inoculation, a form of “prebunking” intended to help people identify and refute false or misleading information, uses short videos in place of ads to highlight manipulative techniques common to misinformation, such as emotional language, false dichotomies and scapegoating. The strategy has already been deployed to millions of users of YouTube, Facebook and other platforms, and could be utilized after the U.S. presidential election.

In a series of studies involving nearly 7,300 online participants, an inoculation video about emotional language improved recognition of that technique – but did not improve people’s ability to discern true headlines from false ones, the researchers found. Participants’ ability to identify true information improved when the video was bookended with video clips prompting them to think about whether content was accurate, suggesting a combined approach could be more effective, the researchers said.

“If you just tell people to watch out for things like emotional language, they’ll disbelieve true things that have emotional language as much as false things that have emotional language,” said Gordon Pennycook, associate professor of psychology. “Encouragingly, we found some synergy between these two approaches, and that means we may be able to develop more effective interventions.”

Pennycook is the first author of “Inoculation and Accuracy Prompting Increase Accuracy Discernment in Combination but Not Alone” under embargo until 5am ET on November 4, 2024 in Nature Human Behavior.

Prior studies involving members of the research team showed that inoculation videos helped people identify manipulative techniques in sample tweets. That raised hopes that a relatively simple intervention could be implemented on a large scale to “immunize” populations against potentially viral misinformation.

The new study investigated whether inoculation’s benefits carried over to more real-world conditions by helping people assess whether information was true or not.

In three initial studies, participants watched the same emotional language video used in the earlier study, which warns viewers to be wary, for example, of headlines referencing a “horrific” accident rather than a “serious” one, or a “disgusting” (versus “disagreeable”) ruling. They then reviewed real headlines – some true, some false – presented in one of two versions the researchers designed: either emotionally neutral or using charged language that could evoke fear or anger. For example, a true, low-emotion headline read, “NYC wants to ‘end the COVID era,’ declares vaccine as a requirement for its workers.” The evocative version read, “Thousands being forced to take the jab: NYC mandates vaccines for its workers.”

Replicating the earlier work, the less than two-minute inoculation video helped study participants flag manipulative content, particularly in high-emotion headlines. But that didn’t make them better at judging which information was accurate – even in the context most favorable for inoculation, when all false headlines contained highly emotional language, and all true headlines were neutral.

“When the task is made more difficult by intermixing actual true or false claims,” the authors wrote, “the video appears to lose its effectiveness as an ‘inoculation against misinformation.’”

A final pair of studies explored the potential benefits of so-called accuracy prompts – simple reminders about the importance of considering accuracy and the threat of misinformation. Like inoculation, accuracy prompts alone proved ineffective for helping people identify true versus false claims (unlike their past use where they successfully improved the news people share). But when the accuracy prompts were sandwiched around the inoculation video, study participants’ identification of true headlines (but not false ones) improved significantly, by up to 10%.

“This shows that combining two techniques that can be readily deployed at scale can boost people’s skills to avoid being misled,” said Stephan Lewandowsky, professor at the University of Bristol, England, and a co-author of the research.

The results have significant implications for the growing field of designing misinformation interventions, the researchers said, highlighting for industry actors and policymakers the importance of testing and deploying multiple interventions in tandem.

“If you’re going to run these interventions, you should probably begin them with a base reminder about accuracy,” Pennycook said. “Just getting people to think more about whether things are true will carry over – at least in the short term – to what they’re seeing and choices about what they would share online.”

In addition to Pennycook and Lewandowsky, co-authors are Adam Berinsky and David Rand ’04, professors at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Puneet Bhargava, a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania; and Hause Lin, a postdoctoral researcher at MIT.

Cornell University has dedicated television and audio studios available for media interviews.

-30-

END

Combining two simple tools could combat election misinformation

2024-11-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Nanoscale transistors could enable more efficient electronics

2024-11-04

CAMBRIDGE, MA – Silicon transistors, which are used to amplify and switch signals, are a critical component in most electronic devices, from smartphones to automobiles. But silicon semiconductor technology is held back by a fundamental physical limit that prevents transistors from operating below a certain voltage.

This limit, known as “Boltzmann tyranny,” hinders the energy efficiency of computers and other electronics, especially with the rapid development of artificial intelligence technologies that demand faster computation.

In an effort to overcome this fundamental limit of silicon, MIT researchers fabricated a different type ...

UChicago scientist develops paradigm to predict behavior of atmospheric rivers

2024-11-04

When torrential rains and powerful winds hit densely populated coastal regions, whole cities can be destroyed—but governments and residents can take precautions with sufficient warning.

Many of these coastal deluges are caused by atmospheric rivers—regions of concentrated water vapor carried along on strong winds, sometimes called “rivers in the sky.” Meteorologists monitor them, but the ability to predict exactly how an atmospheric river might behave based on its underlying physics would offer more precise forecasts.

In a paper published today in Nature Communications, senior author Da Yang, assistant professor of geophysical sciences at the University ...

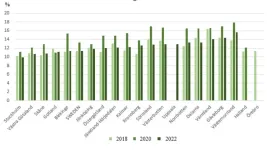

Childhood overweight is associated with socio-economic vulnerability

2024-11-04

More children have overweight in regions with high rates of single parenthood, low education levels, low income and high child poverty. The pandemic may also have reinforced this trend. This is shown by a study conducted by researchers at Uppsala University and Region Sörmland in collaboration with Region Skåne.

“During and after the pandemic, we see a greater difference between regions in terms of children's weight. It even looks like it has exacerbated health inequalities,” explains ...

Study reveals links between many pesticides and prostate cancer

2024-11-04

Researchers have identified 22 pesticides consistently associated with the incidence of prostate cancer in the United States, with four of the pesticides also linked with prostate cancer mortality. The findings are published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

To assess county-level associations of 295 pesticides with prostate cancer across counties in the United States, investigators conducted an environment-wide association study, using a lag period between exposure and prostate cancer incidence of 10–18 years to account for the slow-growing nature of most prostate cancers. The years 1997–2001 ...

LiU researchers make AlphaFold predict very large proteins

2024-11-04

The AI tool AlphaFold has been improved so that it can now predict the shape of very large and complex protein structures. Linköping University researchers have also succeeded in integrating experimental data into the tool. The results, published in Nature Communications, are a step toward more efficient development of new proteins for, among other things, medical drugs.

In all living organisms, there is a huge variety of proteins that regulate cell functions. Basically, everything that happens in the body, from controlling muscles and forming hair to transporting ...

Fossil of huge terror bird offers new information about wildlife in South America 12 million years ago

2024-11-04

**EMBARGOED UNTIL RELEASE MONDAY, NOV. 4, AT 1 A.M. ET**

Researchers including a Johns Hopkins University evolutionary biologist report they have analyzed a fossil of an extinct giant meat-eating bird — which they say could be the largest known member of its kind — providing new information about animal life in northern South America millions of years ago.

The evidence lies in the leg bone of the terror bird described in new paper published Nov. 4 in Palaeontology. The study was led by Federico J. Degrange, a terror bird ...

Scientists create a world-first 3D cell model to help develop treatments for devastating lip injuries

2024-11-04

We use our lips to talk, eat, drink, and breathe; they signal our emotions, health, and aesthetic beauty. It takes a complex structure to perform so many roles, so lip problems can be hard to repair effectively. Basic research is essential to improving these treatments, but until now, models using lip cells — which perform differently to other skin cells — have not been available. In a new study published in Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, scientists report the successful immortalization of donated lip cells, ...

One-third of patients with cancer visit EDs in months before diagnosis

2024-11-04

About 1 in 3 patients diagnosed with cancer in Ontario visited an emergency department (ED) in the 90 days before diagnosis, found a new study published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) https://www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.240952.

In a study that included more than 650 000 patients diagnosed with cancer between 2014 and 2021 in Ontario, 35% (229 683) had visited an ED in the 90 days before diagnosis. Among patients with ED visits before their cancer diagnosis, 64% had visited once, 23% had visited twice and 13% had 3 or more visits. ...

Adolescent exam anxiety can be intensified by pressure to achieve, says academic

2024-11-04

Former teacher Professor of Education David Putwain says ‘heavy-handed’ messages around test results can fuel extreme worry among some 16 to 18-year-olds, even when others respond well to such messages.

Putwain identifies several risk factors, for example students with certain personality traits, including those who are highly self-critical, can underachieve because of severe anxiety in exams. Certain demographics also report higher exam anxiety, including female persons and those from economically deprived backgrounds.

‘Temperature checks’ to identify at-risk ...

A digital health behavior intervention to prevent childhood obesity

2024-11-03

About The Study: A health literacy-informed digital intervention improved child weight-for-length trajectory across the first 24 months of life and reduced childhood obesity at 24 months. The intervention was effective in a racially and ethnically diverse population that included groups at elevated risk for childhood obesity.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, William J. Heerman, MD, MPH, email Bill.Heerman@vumc.org.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jama.2024.22362)

Editor’s ...