(Press-News.org) As bird populations dwindle across the globe, a new study from University of Vermont researchers suggests some species may be more flexible to habitat changes than previously understood, creating new opportunities for supporting populations through city planting efforts. The team’s findings were published in the Journal of Animal Ecology today.

While studies have found bird populations are on the decline—Canada and the United States have lost nearly three billion birds over the last half century—measuring waning populations isn’t simple, particularly in the absence of longitudinal datasets that measure the same variables over time. That is why scientists often use space-for-time substitutions—a method for predicting future species counts using habit associations measured at one point in time.

Harold Eyster, a climate scientist for the Nature Conservancy and lead author of the study, analyzed datasets of breeding bird species surveyed in the Vancouver, Canada metro area from 1997 to 2020 and land cover change assembled using photos, satellite imagery, and machine learning methods, to test the validity of space-for-time methods. His team found total bird populations declined 26 percent, with the biggest reductions—up to 80 and 90 percent—in house sparrows, barn swallows, and starlings. Land cover changes only accounted for part of population shifts, suggesting some ecological models may be overvaluing the strength of habitat-bird relationships.

“It’s not consistent,” explains Eyster, who led this research while a postdoc at UVM’s Gund Institute for Environment. “It might be a signal that maybe we should be thinking about expanding some of the surveys that we are supporting. … We are measuring one thing—breeding birds—but birds have to survive the rest of the year too. So, we have to also think about protecting areas and conserving landscapes that are going to help them the rest of the year.”

In 1997, the most common bird species in the metro Vancouver area were the European starling, house sparrow, American crow, house finch, and violet-green swallow. By 2020, chickadees and bushtits pushed swallows and sparrows out of the top five, and scientists found large increases in species such as the northern flicker. The swings in population growth and decline across bird species don’t align with predicted space-for-time substitutions, meaning scientists may also be overestimating and underestimating the losses of certain bird populations.

Brian Beckage, a professor with joint appointments in UVM’s Department of Plant Biology and Computer Science, and a co-author of the study, says the study’s results reflect the nature of complex systems. “Whenever you're fitting a model to a dataset at one point in time, there are a lot of other things going on in the environment … and so you're conditioning on a lot of things that you're not really aware you're conditioning on.”

For instance, while there may be large-scale regional changes to an environment, there are also local landscape changes that can mitigate—or exacerbate—the effects on wildlife. This is where longitudinal datasets can help scientists tease apart the relationships that matter most and understand what levers humans can pull to buoy wildlife populations in a period of global change.

“Longitudinal data allows you to start seeing how these relationships change over time, how variable they are, what some of the underlying factors that drive the relationships,” Beckage explains. “You can begin to understand when those variables are important, and how they are important, and when they interact.”

The study was funded by Environment and Climate Change Canada to investigate potential nature-based solutions to climate change, such as city planting initiatives, and their effects on bird populations in urban landscapes. Eyster and Backage previously found that conifers may be better at cooling the Vancouver area during heat waves, which benefits both humans and wildlife. But planting trees has myriad health advantages.

“It can improve the quality of the environment for people; it can directly mitigate climate change because trees absorb more carbon; it can mitigate local effects of climate change like heat because it provides more shade,” Beckage explains. “It can also provide more habitat for birds. It also gives people agency to make the world better in all these different ways by doing something that’s not that hard to do.”

While many of the bird species in metro Vancouver exhibiting the steepest population losses are considered nonnative to North America, they often live in the densest areas and may represent some of the only interactions people have with wildlife. As more than half of the world’s population lives in cities, urban environments provide a critical opportunity for fostering positive human and wildlife interactions.

In 2020, Eyster replicated birding surveys in the Vancouver area from the '60s and '70s conducted outside the breeding season and found that many bird species have more flexible and complex behavior than reflected in breeding bird surveys. These species may be more adaptable to changes in land cover than previously understood.

“A lot of our ideas about birds are based on people going out in the 1900s, or even earlier,” Eyster explains. “But … birds are smart. They are flexible. They are able to culturally adapt. Part of what my research is to be really open to that and not assume that birds are going to eat the same things that they did in the '60s when forests were different.”

For instance, certain birds, like the Pacific Wren, appear finicky. During the breeding season, they nest in large forest expanses in British Columbia. However, Eyster found the wrens venture into new territory in the fall and winter. “They're moving into people's cedar hedgerows in their yards. They move into these completely different landscapes,” he says, “and we've actually seen an increase in how they're using the rest of these cities.”

Perhaps they are adapting to a changing landscape, he continues. “… And maybe what we do is not just protect those big parks, but also actually the whole landscape matters.”

He argues urban planners should not ignore the importance of these in between spaces in cities. Large expanses of forest and fields may be important for species during the breeding season, but residential backyards and neighborhood shrubbery also provide sources of food such as berries and seeds that are vital at different times of the year.

It’s easy to initially point to climate change as the primary culprit of bird population declines. But it’s harder to pin down their disappearances to climate change alone. Habitat loss, changes in food supply, or competition from newly introduced species are factors, too.

“One of the things that I am interested in is thinking about ways to disentangle some of those things,” Eyster says.

For him, unraveling the complexity involved in species decline means better understanding the web of relationships affecting them—especially the human ones. And cities may be an ideal place to start.

The study was co-authored by Kai M.A. Chan of the University of British Columbia, Morgan E. Fletcher, an undergraduate at UVM, and Brian Beckage.

END

UVM scientists find space-for-time substitutions exaggerate urban bird–habitat ecological relationships

2024-11-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Molecular Frontiers Symposium in Hong Kong “Frontiers of New Knowledge in Science”

2024-11-07

Event Date: 15 November 2024 to 17 November 2024

Time: 9:00am - 6:30pm

Venue: Main Hall, Shaw Auditorium, HKUST

INTRODUCTION

The Molecular Frontiers Symposium, organized by the globally renowned Molecular Frontiers Foundation - founded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences - is recognized as one of the most influential scientific organizations worldwide.

For the first time in the organization’s history, the Foundation's annual flagship symposium will be held in Greater China, hosted at The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

With the theme "Frontiers of New Knowledge in Science", the Symposium ...

Scientists reveal strigolactone perception mechanism and role in tillering responses to nitrogen

2024-11-07

“How is plant growth controlled?” and “What is the basis of variation in stress tolerance in plants?” were among the 125 most challenging scientific questions, according to the journal Science in 2016.

Strigolactone (SL) is an important plant hormone that plays essential roles in regulating branch number, a key growth and development trait for plants. Recently, scientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) have uncovered the mechanism behind SL perception and its key role in the tillering response to nitrogen.

The “gas and brake” mechanism of SL perception allows “smart and flexible” regulation of the duration ...

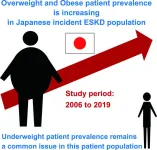

Increasing trend of overweight and obesity among Japanese patients with incident end-stage kidney disease

2024-11-07

Niigata, Japan - A new nationwide study from Japan spanning a 14 year study period has revealed an increasing trend of overweight and obesity in patients with the incident end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). Although, underweight individuals remain prevalent in this patient population, the study highlights that excessive weight and obesity in patients with the incident ESKD is a shared global challenge. Consequently, the study suggests the need for public health strategies to address the global obesity epidemic as well as underweight individuals in incident ESKD populations.

“The global ...

An extra five minutes of exercise per day could help to lower blood pressure

2024-11-07

Adding small amounts of exercise into daily routine, such as climbing stairs or cycling to the shops, could help to reduce blood pressure, with just five additional minutes a day estimated to yield improvements, finds a new study from researchers at UCL and the University of Sydney.

The study, supported by the British Heart Foundation (BHF) and published in Circulation, analysed health data from 14,761 volunteers who wore activity trackers to explore the relationship between daily movement and blood pressure.

The researchers split daily activity into six behaviours1:

Sleep

Sedentary behaviour (such as sitting)

Slow walking (cadence ...

Five minutes of exercise a day could lower blood pressure

2024-11-07

New research suggests that adding a small amount of physical activity – such as uphill walking or stair-climbing – into your day may help to lower blood pressure.

The study, published in Circulation, was carried out by experts from the ProPASS (Prospective Physical Activity, Sitting and Sleep) Consortium, an international academic collaboration led by the University of Sydney and University College London (UCL).

Just five minutes of activity a day was estimated to potentially reduce blood pressure, while replacing ...

Social media likes and comments linked to young men’s obsession with perfect pecs and a six-pack

2024-11-06

Social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram are fuelling unrealistic, unhealthy obsessions with a lean and muscular physique among many young men, according to a new Australian study.

Men who place higher importance on receiving likes and positive comments on their posts are significantly more likely to experience symptoms of what is termed “muscle dysmorphia” (MD) – a belief that their bodies are small and weak, even though many of them have a good physique.

In an online survey of almost 100 men, aged between 18-34, all admitted to viewing celebrity, fashion, and fitness content on social media sites, but the link with MD was only significant when it came to ...

$2.1M aids researchers in building chemical sensors to safeguard troops

2024-11-06

The U.S. Army has awarded a team of researchers led by Judith Su, University of Arizona associate professor of biomedical engineering and optical sciences, $2.1 million to build a handheld version of her record-breaking FLOWER sensing device for active military personnel.

The device picks up target compounds at zeptomolar (10 to the power of negative 21) concentrations, an astonishingly minuscule amount of 600 particles per liter. FLOWER is useful for drug testing and a wide variety of other applications, such as health diagnostics.

The military ...

Climate change parching the American West even without rainfall deficits

2024-11-06

Key takeaways

Higher temperatures caused by anthropogenic climate change turned an ordinary drought into an exceptional one that parched the American West from 2020–2022.

A study by UCLA and NOAA scientists has found that evaporation accounted for 61% of the drought’s severity, while reduced precipitation accounted for 39%.

The research found that since 2000, evaporative demand has played a bigger role than reduced precipitation in droughts, which may become more severe ...

Power grids supplied largely by renewable sources experience lower intensity blackouts

2024-11-06

New research into the vulnerability of power grids served by weather-dependent renewable energy sources (WD-RESs) such as solar and wind paints a hopeful picture as various countries around the globe attempt to meet their climate emissions targets – with the research showing grids with high penetration of WD-RESs tend to have reduced blackout intensities in the US.

This research – just published in leading international journal Nature Energy – was conducted with US blackout data from 2001 to 2020, but the results are of great interest from the perspective of any country transitioning to power grids primarily ...

Scientists calculate predictions for meson measurements

2024-11-06

UPTON, N.Y. — Nuclear physics theorists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory have demonstrated that complex calculations run on supercomputers can accurately predict the distribution of electric charges in mesons, particles made of a quark and an antiquark. Scientists are keen to learn more about mesons — and the whole class of particles made of quarks, collectively known as hadrons — in high-energy experiments at the future Electron-Ion ...