(Press-News.org) A team of scientists led by Caltech and Emory University has synthesized a highly complex natural molecule using a novel strategy that functionalizes normally nonreactive bonds, called carbon–hydrogen (C–H) bonds. The work demonstrates a new category of reactions that organic chemists can consider as they work to create natural products that could be used in pharmaceuticals or new materials, or to produce organic chemicals in more sustainable ways.

"This work moves the field forward by showing the power of C–H functionalization," says Brian Stoltz, the Victor and Elizabeth Atkins Professor of Chemistry at Caltech, a Heritage Medical Research Institute Investigator, and co-corresponding author of a paper describing the new method in the journal Science. "I think this paper shows that you can use these very selective, very interesting, and very unusual transformations even in a complex setting where you have a lot of competing reactive positions. It just opens up a lot of chemistry that you wouldn't have considered before."

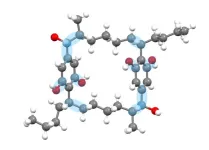

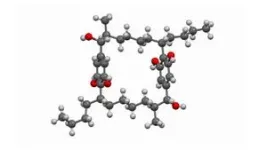

Typically, in organic chemistry, C–H bonds are considered nonreactive, or inert. Such bonds are difficult to break and usually provide a strong, stable scaffold for molecules; chemical transformations, meanwhile, typically involve more reactive groupings of chemicals known as functional groups. The new work flips this model by using a number of new catalysts and carefully designed transformations that allow a series of reactions to occur at C–H bonds. The total synthesis, which involves a total of 10 C–H functionalization steps, ultimately produces a complex molecule called cylindrocyclophane A, a natural product with antimicrobial properties starting from low-cost materials.

"It's by far the most complex natural product we have made using our method," says Huw Davies, a professor of chemistry at Emory and co-corresponding author of the paper.

The new method creates new possibilities for synthesizing previously unavailable chemicals. "It's like a farmer being able to grow crops in the desert or in Antarctica," Davies explains. "C–H functionalization represents a whole new way for chemists to synthesize material in what were once barren [chemical] sites. It opens the possibility for synthesizing materials that are completely different from anything we’ve known."

The work grew out of the National Science Foundation (NSF)-funded Center for Selective C–H Functionalization (CCHF) led by Davies, which began in 2009 and eventually included 25 professors from 15 American universities with additional global connections. The center, Stoltz and Davies say, has encouraged a new collaborative culture within the field.

"Prior to the CCHF, organic chemistry was really very insular," Stoltz says. "Individual investigators tended to covet their ideas. They would only present their findings to those outside of the lab when they had proven results."

"We all recognized the grand challenge before us," Davies says, "and developed the trust needed to combine our expertise rather than compete."

That collaborative spirit led to the sharing of project ideas and progress, regular team exercises in dreaming up novel syntheses, and virtual symposia, where students presented their research and ideas across specialties.

In 2015, such a virtual symposium sparked the collaboration that led to the new Science paper. During that talk, Kuangbiao Liao, then a graduate student at Emory University, described new types of catalysts known as dirhodium catalysts to drive C–H functionalization.

The new catalysts streamlined the process of C–H functionalization by eliminating the need to introduce a separate chemical with what is called a directing group that would target a specific C–H bond. Instead, the three-dimensional exteriors of the catalysts act like a lock and key, allowing only one particular C–H bond in a compound to approach the catalyst and undergo the reaction.

Stoltz immediately saw that this new chemistry had potential for the synthesis of cylindrocyclophane A. He shot Davies an email, and within days, the two labs began working to synthesize the compound using the new approach.

As the project developed, the team realized it provided the opportunity to highlight the impact of C–H functionalization by utilizing a variety of strategies developed through the CCHF.

Along the way, the team expanded the repertoire of C–H methods that could be applied to the synthesis by bringing in co-author Jin-Quan Yu, a chemist at the Scripps Research Institute, an expert in C-H oxidation catalysis and a co-author on the new paper. "The way we approach this molecule is with a very unusual strategy," says Stoltz, "and I don't think this ever would have happened without the multi-institutional aspect of this project."

In addition to the professors from three research institutions, other co-authors include students from each of those institutions. Lead author Aaron Bosse completed the work as a graduate student at Emory. There, he mentored Camila Suarez. Suarez, who was a sophomore when the project launched, continued working on the project after joining the Stoltz lab at Caltech as a graduate student in 2020.

As part of CCHF exchanges, Bosse spent a month at Caltech in the Stoltz lab.

"He worked with our students here to make a final push on the project," Stoltz says. "That set the final stage to make it possible to complete the synthesis, although some challenges remained."

This past summer, Suarez, who bridged the project from beginning to end, helped with the final push on the Science paper with Liam Hunt, a visiting graduate student at Caltech from the University of Auckland. "Cami performed really key experiments that made the paper even stronger," Stoltz says.

Over the summer, Suarez first had to produce the material to work with on campus and then tested many different reaction conditions to see if she could get one final chemical transformation to work in "one pot," using just one step. "And it did, which was really surprising and exciting," Suarez says. "This is the first case where you're able to do the Davies labs’ rhodium-catalyzed C-H functionalization reaction twice in one step. I think this is very enabling technology that we weren't aware was possible before."

Reflecting on the work that she has been a part of for five years, Suarez says, "It's exciting that you can think of a very new way to break bonds. New reactions are being developed every single day, and they're becoming more robust, more powerful, more selective for very unusual and interesting transformations. Because of this innovation, we're able to think of new ways to synthesize natural products, and I feel like that's really important because organic chemistry is such a fundamental science that is involved in so many other sciences."

Additional authors on the paper, "Total synthesis of (-)-cylindrocyclophane A facilitated by C-H functionalization," are Hojoon Park from Scripps; Scott Virgil, director of the Caltech Center for Catalysis and Chemical Synthesis and a lecturer in chemistry at Caltech; and Tyler Casselman (PhD ’23), Elizabeth Goldstein (PhD ’20), and Austin Wright (PhD ’20) who worked on the project while students at Caltech. The work was supported by the NSF, the National Institute of Health's National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the Heritage Medical Research Investigators Program, and the University of Auckland Doctoral Scholarship Award.

END

Breaking carbon–hydrogen bonds to make complex molecules

2024-11-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Sometimes you're the windshield: Utah State University researcher says vehicles cause significant bee deaths

2024-11-08

LOGAN, UTAH, USA -- When a large mammal such as a deer or a moose is struck by a motor vehicle, the damage is usually dramatic. To reduce these unfortunate events, transportation officials have teamed with wildlife researchers to place warning signs, and to construct wildlife underpasses and overpasses, to mitigate mishaps along animal migration paths.

In contrast, collisions with much smaller bees often go unnoticed or are perceived by motorists as simply an annoying splat on a windshield. The significance, Utah State University ...

AMS Science Preview: Turbulence & thunderstorms, heat stress, future derechos

2024-11-08

The American Meteorological Society continuously publishes research on climate, weather, and water in its 12 journals. Many of these articles are available for early online access–they are peer-reviewed, but not yet in their final published form.

Below is a selection of articles published early online recently. Some articles are open-access; to view others, members of the media can contact kpflaumer@ametsoc.org for press login credentials.

JOURNAL ARTICLES

A New Heat Stress Index For Climate Change Assessment

Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society

Heat Index may dramatically underestimate heat stress in extreme temperatures. This work compares the ...

Study of mountaineering mice sheds light on evolutionary adaptation

2024-11-08

Teams of mountaineering mice are helping advance understanding into how evolutionary adaptation to localized conditions can enable a single species to thrive across diverse environments.

In a study led by Naim Bautista, a postdoctoral researcher in Jay Storz’s lab at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, the team took highland deer mice and their lowland cousins on a simulated ascent to 6,000 meters. The “climb” ventured from sea level and the mice reached the simulated summit seven weeks later. Along the way, Bautista tracked how the mice responded to cold stress at progressively lower oxygen levels.

“Deer ...

Geologists rewrite textbooks with new insights from the bottom of the Grand Canyon

2024-11-08

LOGAN, UTAH, USA – Any boomer, gen xer, millennial, gen zer or alpha who’s studied geology has likely gained foundational knowledge from Edwin Dinwiddie McKee’s landmark studies of the Grand Canyon’s sedimentary record – even if they don’t readily recognize McKee’s name.

The legendary scientist, who lived from 1906-1984, studied and documented the stratigraphy and sedimentation of Colorado Plateau geology, especially the Grand Canyon’s Cambrian Tonto Group, for more than 50 years. His time-tested ...

MSU researcher develops promising new genetic breast cancer model

2024-11-08

A Michigan State University researcher’s new model for studying breast cancer could help scientists better understand why and where cancer metastasizes.

Professor https://directory.natsci.msu.edu/Directory/Profiles/Person/103559 who teaches in the MSU Department of Physiology, has been researching the E2F5 gene, of which little is known, and its role in the development of breast cancer. Based on findings from Andrechek’s lab, the loss of E2F5 results in altered regulation of Cyclin D1, a protein linked to metastatic breast tumors after long ...

McCombs announces 2024 Hall of Fame inductees and rising stars

2024-11-08

AUSTIN, Texas — Friends and distinguished alumni of the McCombs School of Business at The University of Texas at Austin inducted four alumni into the school’s Hall of Fame on Nov. 7 at the AT&T Hotel and Conference Center. This year’s honorees are Christopher Bake, BBA ’88; Ray Brimble, B.A. ’74; Bennett Glazer, BBA ’68; and Brien Smith, BBA ’79, MPA '81. McCombs Dean Lillian Mills also recognized 2024 Rising Stars Simeon Bochev, MSF ’13; Michael Ginnings, BBA ’09; and Gerardo Guardado, MBA ’10.

The ...

Stalling a disease that could annihilate banana production is a high-return investment in Colombia

2024-11-08

There’s no cure for a fungal disease that could potentially wipe out much of global banana production. Widespread adoption of cement paths, disinfection stations, and production strategies could net 3-4 USD of benefits for each dollar invested in Colombia.

Hundreds of millions of dollars in banana exports from Colombia are at risk due to a fungal disease best known as Tropical Race 4 (TR4). First detected in Asia in the 1990s, the Fusarium fungus that causes the disease arrived in Colombia in 2019, completing its inevitable global spread to South America, the last major banana production continent that remained TR4-free. Researchers are confident ...

Measurements from ‘lost’ Seaglider offer new insights into Antarctic ice melting

2024-11-08

New research reveals for the first time how a major Antarctic ice shelf has been subjected to increased melting by warming ocean waters over the last four decades.

Scientists from the University of East Anglia (UEA) say the study - the result of their autonomous Seaglider getting accidentally stuck underneath the Ross Ice Shelf - suggests this will likely only increase further as climate change drives continued ocean warming.

The glider, named Marlin, was deployed in December 2022 into the Ross Sea from the edge of the sea ice. Carrying a range of sensors to collect data on ocean processes that are important for climate, it was programmed to travel northward into ...

Grant to support new research to address alcohol-related partner violence among sexual minorities

2024-11-08

Navigating the intersection of alcohol use and intimate partner violence amongst young couples is not an easy journey, and for bisexual+ couples, the road may be even more winding.

“No study has examined the extent to which alcohol use increases intimate personal violence among bisexual+ young adults or daily experiences unique to them. Our study will look at factors such as minority stressors that may lead to alcohol-related partner violence,” said Meagan Brem, director of the Research for Alcohol and Couple’s Health Lab at Virginia Tech.

Alcohol use and intimate partner violence - defined as any action in a ...

Biodiversity change amidst disappearing human traditions

2024-11-08

A Branco Weiss Fellowship – Society in Science has been awarded to Dr Gergana Daskalova. The fellowship funds Daskalova’s research project “Biodiversity change amidst disappearing human traditions and changing socio-economics”. She joins the Department of Conservation Biology at the University of Göttingen to work together with Professor Johannes Kamp. The five-year fellowship, which is worth over €530,000, will enable Daskalova to investigate the ecological and human fingerprints of land abandonment. Considering the question from both a local and a global perspective, Daskalova’s research will reveal what happens to nature when people leave, ...