New roles in infectious process for molecule that inhibits flu

In study, lack of immune protein increases risk of infection by unfamiliar viruses

2024-11-14

(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio – Researchers have identified new roles for a protein long known to protect against severe flu infection – among them, raising the minimum number of viral particles needed to cause sickness.

The protein also helps prevent unfamiliar viruses from mutating after they infect a new host, the study found – meaning its absence during an immune response could enable an animal virus spilled over to people to adapt rapidly to human hosts.

The combined findings by scientists at The Ohio State University add up to potential trouble for people deficient in the protein, called IFITM3 – especially if an avian or swine flu were to gain hold in humans and cause widespread disease.

IFITM3 deficiency is not rare: About 20% of Chinese people and 4% of people of European ancestry have genetic mutations that disable the immune system’s production of the protein.

“An IFITM3 deficiency makes it easier for a low dose of virus to be infectious,” said senior study author Jacob Yount, professor of microbial infection and immunity in Ohio State’s College of Medicine.

Currently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is tracking the H5N1 avian flu that is widespread in wild birds worldwide and causing outbreaks in poultry and U.S. dairy cows. To date, 45 human cases have been reported.

“It’s these emergent viruses that we’ve never encountered before where IFITM3 is really the most important,” Yount said. “Our study supports the idea that not only would you get a more severe infection, but you’re more likely to get infected in the first place and more likely to help the virus adapt if you are IFITM3 deficient.”

The research was published Oct. 30 in Nature Communications.

IFITM3 (pronounced I-fit-M-3, for interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3) is key to the innate immune system’s clearance of viruses. It is produced in large quantities after flu is present and lowers the severity of infection by sequestering the virus so that it can’t make copies of itself, or replicate.

Yount has studied flu and this protein for years, and his lab developed a mouse model lacking the gene that codes for IFITM3 – making the animals highly susceptible to flu.

In this new work, his team sought to extend what is known about IFITM3 to risks related to interspecies infection – specifically the spillover of avian or swine flu to humans, which caused the 1918 influenza pandemic and three others since.

The researchers compared the infectiousness of two strains of avian flu, including H5N1, at different viral particle levels in mice lacking the IFITM3 gene and normal mice. At levels roughly equivalent to 10 and 50 particles, viral loads could be detected in all mice, but in the protein-deficient mice, the equivalent of a single viral particle was able to cause infection and inflammation – while normal mice could not be infected by the low dose.

“IFITM3 has been known to prevent severity of infection, but we’re newly showing that it’s also controlling how much virus it takes initially to cause infection,” Yount said. “And I think that’s one of the most fundamental textbook-level findings ever to come out of my lab.”

Additional experiments in cultures of human cells that line the lung and immune cells showed that cells in which the gene for IFITM3 was silenced were more susceptible to infection by 11 avian, three swine and two human influenza viruses.

“Every single one of those viruses infected at a higher rate when IFITM3 was deficient. So this really seems to be a universal property where IFITM3 needs to be there to inhibit flu infections,” Yount said.

The team then used lab techniques to mimic repeated transmission of a human-origin virus in mice, testing the protein’s role in the pace of mutations that lead to interspecies adaptation. Experiments showed that flu viruses were able to replicate more rapidly and induce higher levels of inflammation in mice deficient in IFITM3 compared to normal mice.

“So a virus from a different species adapts faster when IFITM3 is not there. This was a proof of principle, because we’re testing it in a mouse,” Yount said.

“Overall, our study is a demonstration that IFITM3 is broadly important for zoonotic virus defense against a whole range of different influenza viruses that could potentially infect humans. And our research suggests that people with hereditary deficiency in IFITM3 are a uniquely vulnerable population for new viruses from animals entering humans.”

The research suggests that individuals with IFITM3 deficiency should be considered in pandemic prevention efforts, he said.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Co-authors are Parker Denz, Samuel Speaks, Adam Kenney, Adrian Eddy, Jonathan Papa, Jack Roettger, Sydney Scace, Emily Hemann, Adriana Forero and Andrew Bowman of Ohio State, and Adam Rubrum and Richard Webby of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

#

Contact: Jacob Yount, Jacob.Yount@osumc.edu

Written by Emily Caldwell, Caldwell.151@osu.edu

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2024-11-14

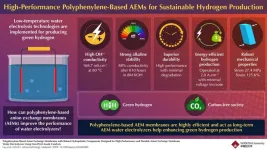

Hydrogen is a promising energy source due to its high energy density and zero carbon emissions, making it a key element in the shift toward carbon neutrality. Traditional hydrogen production methods, like coal gasification and steam methane reforming, release carbon dioxide, undermining environmental goals. Electrochemical water splitting, which yields only hydrogen and oxygen, presents a cleaner alternative. While proton exchange membrane (PEM) and alkaline water electrolyzers (AWEs) are available, they face limitations in either cost or efficiency. PEM electrolyzers, for instance, rely on costly platinum group metals (PGMs) as catalysts, whereas ...

2024-11-14

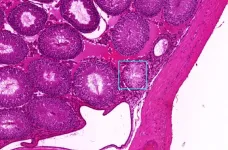

PULLMAN, Wash. – A “deep learning” artificial intelligence model developed at Washington State University can identify pathology, or signs of disease, in images of animal and human tissue much faster, and often more accurately, than people.

The development, detailed in Scientific Reports, could dramatically speed up the pace of disease-related research. It also holds potential for improved medical diagnosis, such as detecting cancer from a biopsy image in a matter of minutes, a process that typically takes ...

2024-11-14

Concreting mistakes can be expensive. Concrete poured too quickly often leads to a lack of colour uniformity, irregularities in the structure and uneven surfaces. Particularly in the case of exposed concrete, expensive reworking using concrete cosmetics is then necessary, sometimes a wall may even have to be demolished. In addition, if the fresh concrete rises too quickly in the formwork, there is a certain risk potential for the workers, as this can cause the formwork to break. In their DigiCoPro project, Ralph Stöckl and ...

2024-11-14

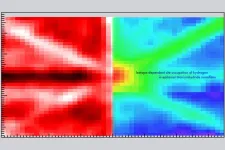

Tokyo, Japan – Although it is the smallest and lightest atom, hydrogen can have a big impact by infiltrating other materials and affecting their properties, such as superconductivity and metal-insulator-transitions. Now, researchers from Japan have focused on finding an easy way to locate it in nanofilms.

In a study published recently in Nature Communications, researchers from the Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo have reported a method for determining the location of hydrogen in nanofilms.

Because they are very small, hydrogen atoms can easily migrate into the framework of other materials. Titanium absorbs hydrogen to give titanium hydrides, making ...

2024-11-14

A new study suggests that political abuse is a key feature of political communication on social media platform, ‘X’, and whether on the political left or right, it is just as common to see politically engaged users abusing their political opponents, to a similar degree, and with little room for moderates.

While previous research into such online abuse has typically focused on the USA, the current study found that abuse followed a common ally-enemy structure across the nine countries for which there was available data: Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, Turkey, ...

2024-11-14

(Santa Barbara, Calif.) — A remote lakeshore deep inside Yosemite National Park teems with life: coyotes, snakes, birds, tadpoles, frogs. The frogs are at the heart of this scene, which a decade ago was much different. It was quiet — and not in a good way. The frogs that are so central to this ecosystem were absent, extirpated by a deadly fungal disease known as amphibian chytrid fungus.

Now, thanks to the consistent and focused efforts of researchers and conservationists to save, then reintroduce, mountain yellow-legged frogs to this and numerous other lakes in Yosemite, their populations are again thriving.

A ...

2024-11-14

ITHACA, N.Y. – By probing chemical processes observed in the Earth’s hot mantle, Cornell scientists have started developing a library of basalt-based spectral signatures that not only will help reveal the composition of planets outside of our solar system but could demonstrate evidence of water on those exoplanets.

“When the Earth’s mantle melts, it produces basalts,” said Esteban Gazel, professor of engineering. Basalt, a gray-black volcanic rock found throughout the solar system, are key recorders of geologic history, he said.

“When the Martian mantle melted, it also produced basalts. The moon is mostly basaltic,” he said. “We’re ...

2024-11-14

Embargoed until 4 a.m. CT / 5 a.m. ET Thursday, November 14, 2024

DALLAS and WASHINGTON, Nov. 14, 2024 — The American Heart Association and the American Red Cross today released the “2024 Guidelines for First Aid,” which provide critical updates that equip first aid responders with the latest evidence-based practices to effectively respond to mild, moderate and life-threatening emergencies. The guidelines are published today in Circulation, the American Heart Association’s flagship journal.

“Providing first aid care is about recognizing that an emergency ...

2024-11-14

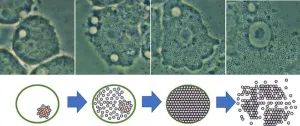

The COVID-19 pandemic led to heightened public interest in learning about viruses and how they can cause diseases. There has been a lot of focus on communicating virology concepts to the general public in order to increase awareness about the spread and prevention of viral diseases.

When it comes to teaching biology, however, how do we explain microscopic processes like viral infections to students in the classroom?

In modern science education, seeing is believing—educators are now attempting to capture the attention of students by using eye-catching visuals and videos, instead ...

2024-11-14

By exploiting the genetic variation in cancer cells, an already approved cancer drug demonstrated enhanced effects against cancer cells in specific patient groups. This is shown in a recent study from Uppsala University, published in the journal eBiomedicine. The findings suggest a potential for more individually tailored and more effective cancer therapies.

The human genome is organised in 46 chromosomes, where all but the x and y chromosomes in men are present in two copies. This means that a person with a faulty gene on one chromosome most often has a functional version on the other. But during ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] New roles in infectious process for molecule that inhibits flu

In study, lack of immune protein increases risk of infection by unfamiliar viruses