(Press-News.org)

To the casual eye, a memory foam mattress would appear to have no relationship to the behavior of cells and tissues. But an innovative study carried out at the Centro de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) in Madrid shows that viscoelasticity—the capacity of a material to be compressed and then recover its original form, like memory foam—is a little-explored property of biological tissues that is essential for correct cell function.

Study leader Dr. Jorge Alegre-Cebollada, who heads the Molecular Mechanics of the Cardiovascular System laboratory at the CNIC, explained that proper cell function requires both biochemical and mechanical signals. Mechanobiology is the scientific study of how cells recognize and respond to the mechanical properties of their surroundings. One of the most important elements in the generation of mechanical signals is the extracellular matrix (ECM), a network of proteins that acts like a glue that holds cells together, thus helping to form and define tissues.

The ECM influences cellular activities through its mechanical properties, regulating migration, proliferation, and differentiation. For example, changes to ECM rigidity are implicated in the progress of coronary artery disease and pancreatic and breast cancers. Nevertheless, scientists still don’t fully understand how cells respond simultaneously to different mechanical properties, such as rigidity and viscolelasticity, especially in predominantly rigid surroundings.

The new study, published in the journal Science Advances, shows that tissue viscoelasticity plays a crucial role in cellular homeostasis, the ability of cells to maintain the internal equilibrium they need to function properly.

“This study represents a significant advance in our understanding of how cells react to mechanical forces and could help to explain, for example, why some tumors are more aggressive than others, as well as pointing the way to improving the performance of artificial tissues in biomedical applications,” commented Dr. Alegre-Cebollada.

In the study, the CNIC-led research team used newly developed biomaterials and a computational model to clarify how cells respond to viscoelastic forces.

Regulation of cellular response times

The study shows that ECM viscoelasticity, a little-studied property until now, regulates the time it takes for cells to respond to a mechanical stimulus.

Dr. Carla Huerta-López, the first author on the study, explained that “in the same way as a memory-foam mattress takes time to recover its shape every morning after we get out of bed, cells and tissues need time to recover from a mechanical stimulus, for example a firm handshake or a knock. The time tissues need to respond to mechanical alterations is determined by viscoelasticity.”

For the study, the CNIC team developed protein-based biomaterials that imitate the mechanical behavior of the ECM.

Using these biomaterials, the authors identified a surprising mechanism through which ECM viscoelasticity outweighs the sensing of rigidity.

According to the researchers, these findings contradict current models and provide new explanations for how cells respond to the mechanical properties of the ECM.

The study has been made possible thanks to the funding received from the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities, the European Research Council (ERC), and the Community of Madrid through the interdisciplinary consortium Tec4Bio-CM. It is worth noting that four of the principal investigators of Tec4Bio-CM have directly participated in the development of this work from the CNIC, ICMM-CSIC, and the Polytechnic University of Madrid.

Huerta-López C, Clemente-Manteca A, Velázquez-Carreras D, Espinosa FM, Sanchez JG, Martínez-del-Pozo A, García-García M, Martín-Colomo S, Rodríguez-Blanco A, Esteban-González R, Martín-Zamora FM, Gutierrez-Rus LI, García R, Roca-Cusachs P, Elosegui-Artola A, Del Pozo MA, Herrero-Galán E, Sáez P, Plaza GR, Alegre-Cebollada J. Cell response to extracellular matrix viscous energy dissipation outweighs high- rigidity sensing. Sci Adv. 2024 Nov 15; 10(eadf9758). doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adf9758

About the CNIC

The CNIC is an affiliate center of the Carlos III Health Institute (ISCIII), an executive agency of the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities. Directed by Dr. Valentín Fuster, the CNIC is dedicated to cardiovascular research and the translation of the knowledge gained into real benefits for patients. The CNIC has been recognized by the Spanish government as a Severo Ochoa center of excellence (award CEX2020-001041-S, funded by MICIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033). The center is financed through a pioneering public-private partnership between the government (through the ISCIII) and the Pro-CNIC Foundation, which brings together 11 of the most important Spanish private companies.

END

Some of the first human beings to arrive in Tasmania, over 41,000 years ago, used fire to shape and manage the landscape, about 2,000 years earlier than previously thought.

A team of researchers from the UK and Australia analysed charcoal and pollen contained in ancient mud to determine how Aboriginal Tasmanians shaped their surroundings. This is the earliest record of humans using fire to shape the Tasmanian environment.

Early human migrations from Africa to the southern part of the globe were well underway during the early part of the last ice age – humans reached northern ...

Recent estimates indicate that deadly antibiotic-resistant infections will rapidly escalate over the next quarter century. More than 1 million people died from drug-resistant infections each year from 1990 to 2021, a recent study reported, with new projections surging to nearly 2 million deaths each year by 2050.

In an effort to counteract this public health crisis, scientists are looking for new solutions inside the intricate mechanics of bacterial infection. A study led by researchers at the University of California San Diego has discovered a vulnerability within strains of bacteria that are antibiotic resistant.

Working with labs at Arizona State University and the Universitat ...

Some of the first humans to arrive in Tasmania, over 41,000 years ago, used fire to shape and manage the landscape, a new study from The Australian National University (ANU) and the University of Cambridge has found.

It is thought to be the earliest and most detailed record of humans using fire in the Tasmanian environment.

According to the researchers, early inhabitants of Tasmania were managing forests and grasslands by burning them to create open spaces, possibly for food procurement and cultural activities.

The team analysed traces of charcoal and pollen contained in ancient mud that showed how Indigenous Tasmanians (Palawa) ...

About The Study: Inferences about clinical impacts based on population-level mean treatment effects may be misleading, since even small between-group differences may reflect clinically important treatment benefits for individual patients. Results of this study suggest that clinical trials should explicitly describe the distributions of Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire change at the patient level within treatment groups to support the clinical interpretation of their results.

Corresponding ...

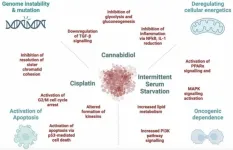

“This commentary will discuss what is known about such combinatorial treatments, including potential mechanisms and future protocols.”

BUFFALO, NY- November 15, 2024 – A new review was published in Volume 11 of Oncoscience on November 12, 2024, entitled, “Targeting carbohydrate metabolism in colorectal cancer - synergy between DNA-damaging agents, cannabinoids, and intermittent serum starvation.”

As highlighted by the authors in the abstract of this review, chemotherapy is a common treatment for many cancers. However, it is often ineffective for long-term patient survival and ...

Stress is a double-edged sword when it comes to memory: stressful or otherwise emotional events are usually more memorable, but stress can also make it harder for us to retrieve memories. In PTSD and generalized anxiety disorder, overgeneralizing aversive memories results in an inability to discriminate between dangerous and safe stimuli. However, until now, it wasn’t clear whether stress played a role in memory generalization.

Now, neuroscientists report November 15 in the Cell Press journal Cell that acute stress prevents mice from forming specific memories. Instead, the stressed mice formed generalized memories, which are ...

PHILADELPHIA—Debate continues to swirl nationally on the fate of a practice born of an 86-year-old federal statute allowing companies to pay workers with disabilities subminimum wages: anything below the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, but for some roles as little as 25-cents-per-hour. Those in favor of repealing this statute highlight assumptions about reduced productivity along with the unfairness of this wage level—often used elsewhere to pay, for example, food service workers who typically make additional wages in tips. Those against repeal have voiced concerns that, without subminimum ...

EMBARGOED: NOT FOR RELEASE UNTIL FRIDAY 15 NOVEMBER 2024 AT 11:00 ET (15:00 UK TIME).

Researchers are calling for a ‘resilience index’ to be used as an indicator of policy success instead of the current focus on GDP.

They say that GDP ignores the wider implications of development and provides no information on our ability to live within our planet’s ‘safe operating space’.

In a paper published today [15 November] in the journal One Earth, researchers from the University of Southampton, UCL ...

Researchers at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) have uncovered that stress changes how our brain encodes and retrieves aversive memories, and discovered a promising new way to restore appropriate memory specificity in people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

If you stumble during a presentation, you might feel stressed the next time you have to present because your brain associates your next presentation with that one poor and aversive experience. This type of stress is tied to one memory. But stress from traumatic events ...

A team of researchers from McGill and Université de Montréal’s Observatoire pour l’éducation et la santé des enfants (OPES, or observatory on children’s health and eduation), led by Sylvana Côté, found that spending two hours a week of class time in a natural environment can reduce emotional distress among 10- to 12-year-olds who had the most significant mental health problems before the program began.

The research comes on the heels of the publication of a UNICEF ...