(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA (November 19, 2024)—Deep breath in, slow breath out… Isn’t it odd that we can self-soothe by slowing down our breathing? Humans have long used slow breathing to regulate their emotions, and practices like yoga and mindfulness have even popularized formal techniques like box breathing. Still, there has been little scientific understanding of how the brain consciously controls our breathing and whether this actually has a direct effect on our anxiety and emotional state.

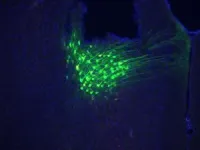

Neuroscientists at the Salk Institute have now, for the first time, identified a specific brain circuit that regulates breathing voluntarily. Using mice, the researchers pinpointed a group of brain cells in the frontal cortex that connects to the brainstem, where vital actions like breathing are controlled. Their findings suggest this connection between the more sophisticated parts of the brain and the lower brainstem’s breathing center allows us to coordinate our breathing with our current behaviors and emotional state.

The findings, published in Nature Neuroscience on November 19, 2024, describe a new set of brain cells and molecules that could be targeted with therapeutics to prevent hyperventilation and regulate anxiety, panic, or post-traumatic stress disorders.

“The body naturally regulates itself with deep breaths, so aligning our breathing with our emotions seems almost intuitive to us—but we didn’t really know how this worked in the brain,” says senior author Sung Han, associate professor and Pioneer Fund Developmental Chair at Salk. “By uncovering a specific brain mechanism responsible for slowing breathing, our discovery may offer a scientific explanation for the beneficial effects of practices like yoga and mindfulness on alleviating negative emotions, grounding them further in science.”

Breathing patterns and emotional state are difficult to untangle—if anxiety increases or decreases, so does the breathing rate. Despite this seemingly obvious connection between emotional regulation and breathing, previous studies had only thoroughly explored subconscious breathing mechanisms in the brainstem. And while newer studies had started to describe conscious top-down mechanisms, no specific brain circuits were discovered until the Salk team took a crack at the case.

The researchers assumed the brain’s frontal cortex, which orchestrates complex thoughts and behaviors, was somehow communicating to a brainstem region called the medulla, which controls automatic breathing. To test this, they first consulted a neural connectivity database and then did experiments to trace the connections between these different brain areas.

These initial experiments revealed a potential new breathing circuit: Neurons in a frontal region called the anterior cingulate cortex were connected to an intermediate brainstem area in the pons, which was then connected to the medulla just below.

Beyond the physical connections of these brain areas, it was also important to consider the types of messages they might send each other. For example, when the medulla is active, it initiates breathing. However, messages coming down from the pons actually inhibit activity in the medulla, leading breathing rates to slow down. Han’s team hypothesized that certain emotions or behaviors could lead cortical neurons to activate the pons, which would then lower activity in the medulla, resulting in slower breath.

To test this, the researchers recorded brain activity in mice during behaviors that alter breathing, such as sniffing, swimming, and drinking, as well as during conditions that induce fear and anxiety. They also used a technique called optogenetics to turn parts of this brain circuit on or off in different emotional and behavioral contexts while measuring the animals’ breathing and behavior.

Their findings confirmed that when the connection between the cortex and the pons was activated, mice were calmer and breathed more slowly, but when mice were in anxiety-inducing situations, this communication decreased, and breathing rates went up. Furthermore, when the researchers artificially activated this cortex-pons-medulla circuit, the animals’ breath slowed, and they showed fewer signs of anxiety. On the other hand, if researchers shut this circuit off, breathing rates went up, and the mice became more anxious.

Altogether, this anterior cingulate cortex-pons-medulla circuit supported the voluntary coordination of breathing rates with behavioral and emotional states.

“Our findings got me thinking: Could we develop drugs to activate these neurons and manually slow our breathing or prevent hyperventilation in panic disorder?” says first author of the study Jinho Jhang, a senior research associate in Han’s lab. “My sister, three years younger than me, has suffered from panic disorder for many years. She continues to inspire my research questions and my dedication to answering them.”

The researchers will continue analyzing the circuit to determine whether drugs could activate it to slow breathing on command. Additionally, the team is working to find the circuit’s converse—a fast breathing circuit, which they believe is likely also tied to emotion. They are hopeful their findings will result in long-term solutions for people with anxiety, stress, and panic disorders, who inspire their discovery and dedication.

“I want to use these findings to design a yoga pill,” says Han. “It may sound silly, and the translation of our work into a marketable drug will take years, but we now have a potentially targetable brain circuit for creating therapeutics that could instantly slow breathing and initiate a peaceful, meditative state.”

Other authors include Shijia Liu, Seahyung Park, and David O’Keefe of Salk.

The work was supported by the Kavli Institute for Brain and Mind (IRGS 2020-1710).

About the Salk Institute for Biological Studies:

Unlocking the secrets of life itself is the driving force behind the Salk Institute. Our team of world-class, award-winning scientists pushes the boundaries of knowledge in areas such as neuroscience, cancer research, aging, immunobiology, plant biology, computational biology, and more. Founded by Jonas Salk, developer of the first safe and effective polio vaccine, the Institute is an independent, nonprofit research organization and architectural landmark: small by choice, intimate by nature, and fearless in the face of any challenge. Learn more at www.salk.edu.

END

Neuroscientists discover how the brain slows anxious breathing

Salk scientists identify brain circuit used to consciously slow breathing and confirm this reduces anxiety and negative emotions

2024-11-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New ion speed record holds potential for faster battery charging, biosensing

2024-11-19

PULLMAN, Wash. – A speed record has been broken using nanoscience, which could lead to a host of new advances, including improved battery charging, biosensing, soft robotics and neuromorphic computing.

Scientists at Washington State University and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have discovered a way to make ions move more than ten times faster in mixed organic ion-electronic conductors. These conductors combine the advantages of the ion signaling used by many biological systems, including the human body, with the electron signaling used by computers.

The new development, detailed in the journal ...

Haut.AI explores the potential of AI-enhanced fluorescence photography for non-invasive skin diagnostics

2024-11-19

Tallinn, Estonia – 19th November 2024, 10 AM CET – Haut.AI, a pioneering artificial intelligence (AI) company for skincare and beauty applications, has published an exciting scientific review—one that explores state-of-the-art developments in skin fluorescence photography and its applications, focusing on combining it with AI algorithms for non-invasive skin diagnostics. The study highlights the power of AI to enhance skin fluorescence photography, allowing early, non-invasive detection of skin conditions. This approach allows skincare experts to diagnose underlying issues ...

7-year study reveals plastic fragments from all over the globe are rising rapidly in the North Pacific Garbage Patch

2024-11-19

A study published today in IOP Publishing’s journal Environmental Research Letters reveals that centimetre-sized plastic fragments are increasing much faster than larger floating plastics in the North Pacific Garbage Patch [NPGP], threatening the local ecosystem and potentially the global carbon cycle.

The research, which draws from not-for-profit The Ocean Cleanup’s systematic surveys of the NPGP between 2015 and 2022, found an unexpected rise in mass concentration of plastic fragments that are ...

New theory reveals the shape of a single photon

2024-11-19

A new theory, that explains how light and matter interact at the quantum level has enabled researchers to define for the first time the precise shape of a single photon.

Research at the University of Birmingham, published in Physical Review Letters, explores the nature of photons (individual particles of light) in unprecedented detail to show how they are emitted by atoms or molecules and shaped by their environment.

The nature of this interaction leads to infinite possibilities for light to exist and propagate, or travel, through its surrounding environment. This limitless ...

We could soon use AI to detect brain tumors

2024-11-19

A new paper in Biology Methods and Protocols, published by Oxford University Press, shows that scientists can train artificial intelligence models to distinguish brain tumors from healthy tissue. AI models can already find brain tumors in MRI images almost as well as a human radiologist.

Researchers have made sustained progress in artificial intelligence (AI) for use in medicine. AI is particularly promising in radiology, where waiting for technicians to process medical images can delay patient treatment. Convolutional neural networks are powerful tools that allow researchers to train AI models on large image datasets to recognize ...

TAMEST recognizes Lyda Hill and Lyda Hill Philanthropies with Kay Bailey Hutchison Distinguished Service Award

2024-11-19

TAMEST is pleased to announce Lyda Hill and Lyda Hill Philanthropies as the recipients of the Kay Bailey Hutchison Distinguished Service Award.

TAMEST is recognizing Lyda Hill and her team for empowering and enabling groundbreaking research in science and nature that profoundly impacts society. Lyda Hill, a successful businesswoman and world-renowned philanthropist, believes science can solve many of the world’s most challenging issues and has chosen to donate all of her estate to philanthropy and scientific research.

Aligned with this mission, Lyda Hill is committed to advancing science and public ...

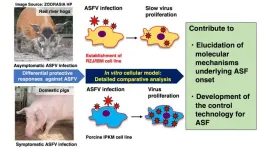

Establishment of an immortalized red river hog blood-derived macrophage cell line

2024-11-19

Red river hogs (RRHs) (Potamochoerus porcus), a wild species of Suidae living in Africa, have grabbed much attention as an animal that harbors African swine fever virus (ASFV) as natural hosts. When ASFV infects domestic pigs and wild boars, it proliferates within macrophages, a type of immune cells, and infected pigs rapidly die suffering from symptoms such as fever and hemorrhage. On the other hand, ASFV infection in RRHs is asymptomatic and does not cause death, suggesting that RRH macrophages may have a protective mechanism against ASFV infection.

In vitro cell cultures of porcine macrophages are generally ...

Neural networks: You might not need to buy every ticket to win the lottery

2024-11-19

The more lottery tickets you buy, the higher your chances of winning, but spending more than you win is obviously not a wise strategy. Something similar happens in AI powered by deep learning: we know that the larger a neural network is (i.e., the more parameters it has), the better it can learn the task we set for it. However, the strategy of making it infinitely large during training is not only impossible but also extremely inefficient. Scientists have tried to imitate the way biological brains learn, which is highly resource-efficient, by providing machines with a gradual training process that starts with ...

Healthy New Town: Revitalizing neighborhoods in the wake of aging populations

2024-11-19

Planned suburban residential neighborhoods in metropolitan areas known as new towns were initially developed in England. The new town movement spread from Europe to East Asia, such as to Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore. In Japan alone, 2,903 New Towns were built, but many experienced rapid population decline and aging in the 40 years after their development. Therefore, they changed into old new towns and had to transform their facilities.

Dr. Haruka Kato, a junior associate professor at Osaka Metropolitan ...

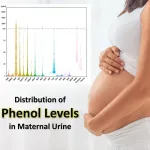

High exposure to everyday chemicals linked to asthma risk in children

2024-11-19

A new study from researchers at Kumamoto University sheds light on a potential link between exposure to certain everyday chemicals during pregnancy and the development of asthma in children. The study analyzed data from over 3,500 mother-child pairs as part of the Japan Environment and Children’s Study (JECS), a large-scale nationwide research project.

Key Findings:

High levels of butylparaben, a chemical commonly used in personal care products like lotions and shampoos, during early pregnancy were associated with a 1.54-fold increase in the odds of asthma development in children ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

U.S. medical care is improving, but cost and health differ depending on disease

AI challenges lithography and provides solutions

Can AI make society less selfish?

UC Irvine researchers expose critical security vulnerability in autonomous drones

Changes in smoking status and their associations with risk of Parkinson’s, death

[Press-News.org] Neuroscientists discover how the brain slows anxious breathingSalk scientists identify brain circuit used to consciously slow breathing and confirm this reduces anxiety and negative emotions