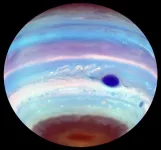

(Press-News.org) While Jupiter's Great Red Spot has been a constant feature of the planet for centuries, University of California, Berkeley, astronomers have discovered equally large spots at the planet's north and south poles that appear and disappear seemingly at random.

The Earth-size ovals, which are visible only at ultraviolet wavelengths, are embedded in layers of stratospheric haze that cap the planet's poles. The dark ovals, when seen, are almost always located just below the bright auroral zones at each pole, which are akin to Earth's northern and southern lights. The spots absorb more UV than the surrounding area, making them appear dark on images from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. In yearly images of the planet taken by Hubble between 2015 and 2022, a dark UV oval appears 75% of the time at the south pole, while dark ovals appear in only one of eight images taken of the north pole.

The dark UV ovals hint at unusual processes taking place in Jupiter's strong magnetic field that propagate down to the poles and deep into the atmosphere, far deeper than the magnetic processes that produce the auroras on Earth.

The UC Berkeley researchers and their colleagues reported the phenomena today (Nov. 26) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Dark UV ovals were first detected by Hubble in the late 1990s at the north and south poles and subsequently at the north pole by the Cassini spacecraft that flew by Jupiter in 2000, but they drew little attention. When UC Berkeley undergraduate Troy Tsubota conducted a systematic study of recent images obtained by Hubble, however, he found they were a common feature at the south pole — he counted eight southern UV-dark ovals (SUDO) between 1994 and 2022. In all 25 of Hubble's global maps that show Jupiter's north pole, Tsubota and senior author Michael Wong, an associate research astronomer based at UC Berkeley's Space Sciences Laboratory, found only two northern UV-dark ovals (NUDO).

Most of the Hubble images had been captured as part of the Outer Planet Atmospheres Legacy (OPAL) project directed by Amy Simon, a planetary scientist at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and a co-author of the paper. Using Hubble, OPAL astronomers make yearly observations of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune to understand their atmospheric dynamics and evolution over time.

"In the first two months, we realized these OPAL images were like a gold mine, in some sense, and I very quickly was able to construct this analysis pipeline and send all the images through to see what we get," said Tsubota, who is in his senior year at UC Berkeley as a triple major in physics, mathematics and computer science. "That's when we realized we could actually do some good science and real data analysis and start talking with collaborators about why these show up."

Wong and Tsubota consulted two experts on planetary atmospheres — Tom Stallard at Northumbria University in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in the UK and Xi Zhang at UC Santa Cruz — to determine what could cause these areas of dense haze. Stallard theorized that the dark oval is likely stirred from above by a vortex created when the planet's magnetic field lines experience friction in two very distant locations: in the ionosphere, where Stallard and other astronomers previously detected spinning motion using ground-based telescopes, and in the sheet of hot, ionized plasma around the planet shed by the volcanic moon Io.

The vortex spins fastest in the ionosphere, progressively weakening as it reaches each deeper layer. Like a tornado touching down on dusty ground, the deepest extent of the vortex stirs up the hazy atmosphere to create the dense spots Wong and Tsubota observed. It's not clear if the mixing dredges up more haze from below or generates additional haze.

Based on the observations, the team suspects that the ovals form over the course of about a month and dissipate in a couple of weeks.

“The haze in the dark ovals is 50 times thicker than the typical concentration,” said Zhang, “which suggests it likely forms due to swirling vortex dynamics rather than chemical reactions triggered by high-energy particles from the upper atmosphere. Our observations showed that the timing and location of these energetic particles do not correlate with the appearance of the dark ovals.”

The findings are what the OPAL project was designed to discover: how atmospheric dynamics in the solar system's giant planets differ from what we know on Earth.

"Studying connections between different atmospheric layers is very important for all planets, whether it's an exoplanet, Jupiter or Earth," Wong said. "We see evidence for a process connecting everything in the entire Jupiter system, from the interior dynamo to the satellites and their plasma torii to the ionosphere to the stratospheric hazes. Finding these examples helps us to understand the planet as a whole."

The work was supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

END

Magnetic tornado is stirring up the haze at Jupiter's poles

Unusual magnetically driven vortices may be generating Earth-size concentrations of hydrocarbon haze

2024-11-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cancers grow uniformly throughout their mass

2024-11-26

Researchers at the University of Cologne and the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona have discovered that cancer grows uniformly throughout its mass, rather than at the outer edges. The work, published today in the journal eLIFE, challenges decades-old assumptions about how the disease grows and spreads.

“We challenge the idea that a tumour is a ‘two-speed’ entity with rapidly dividing cells on the surface and slower activity in the core. Instead, we show they are uniformly growing masses, where every region is equally active and has the potential ...

Researchers show complex relationship between Arctic warming and Arctic dust

2024-11-26

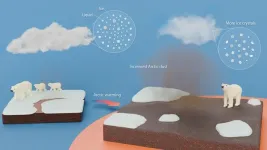

The Arctic is warming two to four times faster than the global average. A recent study by researchers in Japan found that dust from snow- and ice-free areas of the Arctic may be an important contributor to climate change in the region. The findings were published in the journal npj Climate and Atmospheric Science.

According to one view, higher temperatures in the Arctic are thought to lead to the region's clouds containing more liquid droplets and fewer ice crystals. Clouds become thicker, longer lasting, ...

Brain test shows that crabs process pain

2024-11-26

Researchers from the University of Gothenburg are the first to prove that painful stimuli are sent to the brain of shore crabs providing more evidence for pain in crustaceans. EEG style measurements show clear neural reactions in the crustacean's brain during mechanical or chemical stimulation.

In the search for a better welfare of animals that we humans kill for food, researchers at the University of Gothenburg have chosen to focus on decapod crustaceans. This includes shellfish delicacies such as prawns, lobsters, crabs and crayfish that we both catch wild and farm. Currently, ...

Social fish with low status are so stressed out it impacts their brains

2024-11-26

Social stress is bad for your brain. It’s a prime suspect in the accumulation of oxidative stress in the brain, which is believed to contribute to mental health and neurodegenerative disorders — but the mechanisms that turn social stress into oxidative stress, and how social status affects this, are poorly understood. By studying a highly social, very hierarchical fish species, cichlids, scientists have now found that social stress raises oxidative stress in the brains of low-status fish.

“We found that low rank was generally linked to higher levels of oxidative stress in the brain,” said Dr Peter Dijkstra of ...

Predicting the weather: New meteorology estimation method aids building efficiency

2024-11-26

Due to the growing reality of global warming and climate change, there is increasing uncertainty around meteorological conditions used in energy assessments of buildings. Existing methods for generating meteorological data do not adequately handle the interdependence of meteorological elements, such as solar radiation, air temperature, and absolute humidity, which are important for calculating energy usage and efficiency.

To address this challenge, a research team at Osaka Metropolitan University’s Graduate School of Human Life and Ecology—comprising Associate ...

Inside the ‘swat team’ – how insects react to virtual reality gaming

2024-11-26

Humans get a real buzz from the virtual world of gaming and augmented reality but now scientists have trialled the use of these new-age technologies on small animals, to test the reactions of tiny hoverflies and even crabs.

In a bid to comprehend the aerodynamic powers of flying insects and other little-understood animal behaviours, the Flinders University-led study is gaining new perspectives on how invertebrates respond to, interact with and navigate virtual ‘worlds’ created by advanced entertainment technology.

Published in the ...

Oil spill still contaminating sensitive Mauritius mangroves three years on

2024-11-26

Three years after bulk carrier MV Wakashio ran aground on a coral reef off Mauritius, spilling 1000 tonnes of a new type of marine fuel oil, Curtin University-led research has confirmed the oil is still present in an environmentally sensitive mangrove forest close to important Ramsar conservation sites.

Lead researcher Dr Alan Scarlett, from Curtin’s WA Organic and Isotope Geochemistry Centre in the School of Earth and Planetary Sciences, said the chemical ‘fingerprint’ of the oil found ...

Unmasking the voices of experience in healthcare studies

2024-11-26

Researchers are calling for a formal process that recognises and acknowledges the invaluable contributions of those with lived experience in healthcare research.

New research by Flinders University published in the Patient Education and Counselling journal exposes underlying issues in academic engagement and calls for better processes to credit those with lived experiences.

“With the growing awareness of the importance of diversity and inclusion in research, it is time for the research community to monitor not only how often, but also how well people with lived experience are involved,” says Associate Professor Elizabeth Lynch.

Associate Professor Lynch from the College of ...

Pandemic raised food, housing insecurity in Oregon despite surge in spending

2024-11-26

Despite a heavy infusion of public and private support during the COVID-19 pandemic, Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries in Oregon reported that housing and food insecurity shot up during the onset of the pandemic in March of 2020 — and their basic needs remained in doubt through at least the end of the following year.

The survey data were reported in a study led by Oregon Health & Science University and published today in the Annals of Family Medicine.

The Oregon study provides a state-specific dimension to a nationwide survey ...

OU College of Medicine professor earns prestigious pancreatology award

2024-11-26

Min Li, Ph.D., a George Lynn Cross Professor of Medicine, Surgery and Cell Biology at the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine and Associate Director for Global Oncology at OU Health Stephenson Cancer Center, will receive the 2024 Palade Prize from the International Association of Pancreatology.

The Palade Prize, the IAP’s most distinguished award for research excellence, recognizes Li’s contributions to the field of pancreatology, which is dedicated to discovering new methods of identifying, diagnosing and treating diseases of the pancreas such as pancreatic ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Breaking the efficiency barrier: Researchers propose multi-stage solar system to harness the full spectrum

A new name, a new beginning: Building a green energy future together

From algorithms to atoms: How artificial intelligence is accelerating the discovery of next-generation energy materials

Loneliness linked to fear of embarrassment: teen research

New MOH–NUS Fellowship launched to strengthen everyday ethics in Singapore’s healthcare sector

Sungkyunkwan University researchers develop next-generation transparent electrode without rare metal indium

What's going on inside quantum computers?: New method simplifies process tomography

This ancient plant-eater had a twisted jaw and sideways-facing teeth

Jackdaw chicks listen to adults to learn about predators

Toxic algal bloom has taken a heavy toll on mental health

Beyond silicon: SKKU team presents Indium Selenide roadmap for ultra-low-power AI and quantum computing

Sugar comforts newborn babies during painful procedures

Pollen exposure linked to poorer exam results taken at the end of secondary school

7 hours 18 mins may be optimal sleep length for avoiding type 2 diabetes precursor

Around 6 deaths a year linked to clubbing in the UK

Children’s development set back years by Covid lockdowns, study reveals

Four decades of data give unique insight into the Sun’s inner life

Urban trees can absorb more CO₂ than cars emit during summer

Fund for Science and Technology awards $15 million to Scripps Oceanography

New NIH grant advances Lupus protein research

New farm-scale biochar system could cut agricultural emissions by 75 percent while removing carbon from the atmosphere

From herbal waste to high performance clean water material: Turning traditional medicine residues into powerful biochar

New sulfur-iron biochar shows powerful ability to lock up arsenic and cadmium in contaminated soils

AI-driven chart review accurately identifies potential rare disease trial participants in new study

Paleontologist Stephen Chester and colleagues reveal new clues about early primate evolution

UF research finds a gentler way to treat aggressive gum disease

Strong alcohol policy could reduce cancer in Canada

Air pollution from wildfires linked to higher rate of stroke

Tiny flows, big insights: microfluidics system boosts super-resolution microscopy

Pennington Biomedical researcher publishes editorial in leading American Heart Association journal

[Press-News.org] Magnetic tornado is stirring up the haze at Jupiter's polesUnusual magnetically driven vortices may be generating Earth-size concentrations of hydrocarbon haze