Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a leading cause of chronic liver diseases, that spreads among individuals through blood or body fluids. According to the World Health Organization, globally 1.2 million new HBV infections are reported every year. Caused by the HBV, these infections are limited to a few species, including humans and chimpanzees. Despite their close evolutionary relationship with these animals, old-world monkeys are not susceptible to HBV infections. In a new study published in Nature Communications on October 25, 2024, scientists including Dr. Kaho Shionoya from the Tokyo University of Science, Dr. Jae-Hyun Park, Dr. Toru Ekimoto, Dr. Mitsunori Ikeguchi, and Dr. Sam-Yong Park from Yokohama City University, along with Dr. Norimichi Nomura from Kyoto University, collaborated under the leadership of Visiting Professor Koichi Watashi from the Tokyo University of Science to uncover why monkeys are naturally resistant to HBV infection.

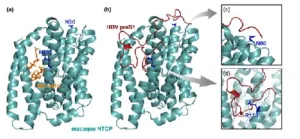

Using cryo-electron microscopy, scientists solved the structure of a membrane receptor found in liver cells called the sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP) in macaques. HBV binds to human NTCP using its preS1 region in the surface protein. Prof. Watashi explains, “We identified a binding mode for NTCP–preS1 where two functional sites are involved in human NTCP (hNTCP). In contrast, macaque NTCP (mNTCP) loses both binding functions due to steric hindrance and instability in the preS1 binding state.”

To understand this ‘interspecies barrier’ against viral transmission, Prof. Watashi and his team compared the structures of hNTCP and mNTCP, identifying differences in amino acid residues critical for HBV binding and entry into liver cells. hNTCP and mNTCP share 96% amino acid homology, with 14 amino acids distinct between the two receptors. A key distinction among these differences is the bulky side chain of arginine at position 158 in mNTCP, which prevents deep preS1 insertion into the NTCP bile acid pocket. For successful viral entry into liver cells, a smaller amino acid like glycine, as found in hNTCP, is necessary.

Interestingly, the substitution of Glycine by Arginine in mNTCP was at a position far away from the binding site for bile acid. Prof. Watashi adds, “These animals probably evolved to acquire escape mechanisms from HBV infections without altering their bile acid transport capacity. Consistently, phylogenetic analysis showed strong positive selection at position 158 of NTCP, probably due to pressure from HBV. Such molecular evolution driven to escape virus infection has been reported for other virus receptors.” Further lab experiments and simulations revealed that an amino acid at position 86 is also critical for stabilizing NTCP’s bound state with HBV’s preS1 domain. Non-susceptible species lack lysine at this position, which has a large side chain; macaques instead have asparagine, which contributes to HBV resistance.

The researchers also noted that bile acids and HBV’s preS1 competed to bind to NTCP, where the long tail-chain structure of the bile acid inhibited the binding of preS1. Commenting on these findings, Prof. Watashi stated, “Bile acids with long conjugated chains exhibited anti-HBV potency. Development of bile acid-based anti-HBV compounds is underway and our results will be useful for the design of such anti-HBV entry inhibitors.”

In a world where the majority of HBV infections are concentrated in low- and middle-income countries, the high costs of treatment pose not only a healthcare crisis but also an economic burden that ripples through societies. This groundbreaking study sheds light on how natural evolution has equipped certain species with defenses against this debilitating disease, marking a pivotal advancement in our understanding of viral interactions. By unraveling the structure of mNTCP and pinpointing the amino acids that facilitate viral entry into liver cells, researchers have opened the door to new therapeutic avenues. Furthermore, the implications extend beyond HBV, offering critical insights into other viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, and their potential to cross species barriers. This research not only enhances our understanding of viral dynamics but also serves as a crucial tool in the ongoing quest to predict and prevent future pandemics.

The future of global health hinges on these revelations, promising a path toward more equitable access to treatments and a stronger defense against emerging viral threats.

***

Reference

Title of original paper: Structural Basis for Hepatitis B Virus Restriction by a Viral Receptor Homologue

Journal: Nature Communications

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-53533-6

About The Tokyo University of Science

Tokyo University of Science (TUS) is a well-known and respected university, and the largest science-specialized private research university in Japan, with four campuses in central Tokyo and its suburbs and in Hokkaido. Established in 1881, the university has continually contributed to Japan's development in science through inculcating the love for science in researchers, technicians, and educators.

With a mission of “Creating science and technology for the harmonious development of nature, human beings, and society,” TUS has undertaken a wide range of research from basic to applied science. TUS has embraced a multidisciplinary approach to research and undertaken intensive study in some of today's most vital fields. TUS is a meritocracy where the best in science is recognized and nurtured. It is the only private university in Japan that has produced a Nobel Prize winner and the only private university in Asia to produce Nobel Prize winners within the natural sciences field.

Website: https://www.tus.ac.jp/en/mediarelations/

About Professor Koichi Watashi from Tokyo University of Science

Professor Koichi Watashi, director of the Division of Drug Development, Research Center for Drug and Vaccine Development at the National Institute of Infectious Diseases and a Visiting Professor at the TUS Graduate School of Science and Technology, has a Ph.D. from Kyoto University. His research interests include the molecular biology of hepatitis viruses and emerging viruses and the development of new anti-viral molecules. He has extensive experience, with over 200 publications and many awards from academic societies to his credit like The Young Investigator Award from the Japanese Cancer Association (JCA), Sugiura Memorial Incentive Award of the Japanese Society for Virology (JSV), and MSD Award of the Japanese Society of Hepatology (JSH).

Funding information

This work was supported by the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED); JSPS/MEXT KAKENHI; JST MIRAI program; the Program for Promoting Research on the Supercomputer Fugaku, computational resources of Fugaku provided by RIKEN through the HPCI System Research Project, and by the grant for 2021-2023 Strategic Research Promotion of Yokohama City University; The Takeda Science Foundation; Japan Foundation for Applied Enzymology; Mitsubishi Foundation; Joint Usage/Research Center Program of the Institute for Life and Medical Sciences at Kyoto University.

END