(Press-News.org) More images and video available- see link in the Notes section.

A new study suggests that the fundamental abilities underlying human language and technological culture may have evolved before humans and apes diverged millions of years ago. The findings will be published 5th December 2024 in the journal PeerJ.

Many human behaviours are more complex than those of other animals, involving the production of elaborate sequences (such as spoken language, or tool manufacturing). These sequences include the ability to organise behaviours by hierarchical chunks, and to understand relationships between distantly separated elements.

For example, even relatively simple human behaviours like making a cup of tea or coffee require carrying out a series of individual actions in the right order (e.g. boiling the kettle before pouring the water out). We break such tasks down into solvable chunks (e.g. boil the kettle, get the milk and teabag, etc), composed of individual actions (e.g. ‘grasp’, ‘pull’, ‘twist’, ‘pour’). Importantly, we can separate related actions by other chunks of behaviour (e.g. you might have to stop and clean up some spilt milk before you continue). It was unknown whether the ability to flexibly organize behaviours in this way is unique to humans, or also present in other primates.

In this new study, the researchers investigated the actions of wild chimpanzees – our closest relatives – whilst using tools, and whether these appeared to be organised into sequences with similar properties (rather than a series of simple, reflex-like responses). The research was led by the University of Oxford with an international collaboration across the UK, US, Germany, Switzerland, and Japan.

The study used data from a decades-long database of video footage depicting wild chimpanzees in the Bossou forest, Guinea, where chimps were recorded cracking hard-shelled nuts using a hammer and anvil stones. This is one of the most complex documented naturally-occurring tool use behaviours of any animal in the wild. The researchers recorded the sequences of actions chimps performed (e.g. grasp nut, pass through hands, place on anvil, etc.) – totalling around 8,260 actions for over 300 nuts.

Using state-of-the-art statistical models, they found that relationships emerged between chimpanzees' sequential actions which matched those found in human behaviours. Half of adult chimpanzees appeared to associate actions that were much further along the sequence than expected if actions were simply being linked together one-by-one. This provides further evidence that chimpanzees plan action sequences, and then adjust their performance on the fly.

Understanding how these relationships emerge during action organization will be the next key goal of this research, but these could involve behaviours such as chimpanzees pausing sequences to readjust tools before continuing, or bringing several nuts over to stone tools that are then cracked in one long sequence. This would be further evidence of human-like technical flexibility.

Additionally, the results suggest that the majority of chimpanzees organise actions similarly to humans, through the production of repeatable 'chunks'. However, this result did not hold for every chimpanzee, and this variation between individuals may suggest that these strategies for organising behaviours may not be universal in the way they are for humans.

Lead researcher Dr Elliot Howard-Spink (formerly Department of Biology, University of Oxford, now Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior) said: “The ability to flexibly organise individual actions into tool use sequences has likely been key to humans’ global success. Our results suggest that the fundamental aspects of human sequential behaviours may have evolved prior to the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees, and then may have been further elaborated on during subsequent hominin evolution.”

Co-senior researcher Professor Thibaud Gruber (University of Geneva) said: “There has been a renewed interest in the co-evolution of language and stone tool use in human evolution, and our study contributes to this debate. While the connection between our results and early hominin stone tool use can be made more readily, how this connects with the evolution of other complex behaviours, like language, remains an exciting avenue of future research.”

Co-senior researcher Professor Dora Biro (University of Rochester) said: “There is increasing recognition that preserving cultural behaviours in wild animals – such as stone-tool use in West-African chimpanzees – should be incorporated into conservation efforts. Wild chimpanzees and their cultures are critically endangered, yet our work highlights how much we can yet learn from our closest relative about our own evolutionary history.”

As many great apes perform dextrous and technical foraging behaviours, it is likely that the capacity for these complex sequences is shared across ape species. More research is needed to validate this theory, and is a key goal for the team moving forward.

The researchers also plan to investigate how actions are grouped into higher-order chunks by chimpanzees during tool-use. This research will aim to clarify the rules that chimpanzees follow when generating their tool use behaviours. They will also investigate how these structures emerge during development and are shaped across adult lives.

Notes to editors

Interviews with Elliot Howard-Spink are available on request: espink@ab.mpg.de or elliot.howardspink@outlook.com

The paper ‘Nonadjacent dependencies and sequential structure of chimpanzee action during a natural tool-use task’ will be published in PeerJ. It will be available online when the embargo lifts at: https://peerj.com/articles/18484/

For enquiries about advanced view of the paper under embargo, contact: Elliot Howard-Spink: espink@ab.mpg.de or elliot.howardspink@outlook.com

Images and videos relating to the study which can be used in articles can be found at https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1CM3AdN3ODoxBzf_5RcpLQWeJpZQWNjZ9?usp=sharing These are for editorial purposes relating to this press release only and MUST be credited (see captions document in file). They MUST NOT be sold on to third parties.

About the University of Oxford

Oxford University has been placed number 1 in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings for the ninth year running, and number 3 in the QS World Rankings 2024. At the heart of this success are the twin-pillars of our ground-breaking research and innovation and our distinctive educational offer.

Oxford is world-famous for research and teaching excellence and home to some of the most talented people from across the globe. Our work helps the lives of millions, solving real-world problems through a huge network of partnerships and collaborations. The breadth and interdisciplinary nature of our research alongside our personalised approach to teaching sparks imaginative and inventive insights and solutions.

Through its research commercialisation arm, Oxford University Innovation, Oxford is the highest university patent filer in the UK and is ranked first in the UK for university spinouts, having created more than 300 new companies since 1988. Over a third of these companies have been created in the past five years. The university is a catalyst for prosperity in Oxfordshire and the United Kingdom, contributing £15.7 billion to the UK economy in 2018/19, and supports more than 28,000 full time jobs.

The Department of Biology is a University of Oxford department within the Maths, Physical, and Life Sciences Division. It utilises academic strength in a broad range of bioscience disciplines to tackle global challenges such as food security, biodiversity loss, climate change, and global pandemics. It also helps to train and equip the biologists of the future through holistic undergraduate and graduate courses. For more information visit www.biology.ox.ac.uk.

END

Chimpanzees perform the same complex behaviors that have brought humans success

2024-12-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Potential epigenetic biomarker found for preeclampsia in pregnancy

2024-12-05

PULLMAN, Wash. – Analysis of cheek swabs taken from pregnant women revealed a potential epigenetic biomarker for preeclampsia, a potentially life-threatening condition that often leads to preterm births.

While a clinical trial is needed to confirm the results, a study published in the journal Environmental Epigenetics offers hope that a simple test can be developed to identify preeclampsia earlier in pregnancy. Currently preeclampsia is usually identified by symptoms, such as abnormally high blood pressure, which only appear in the second trimester of pregnancy. Sometimes the condition can go undetected ...

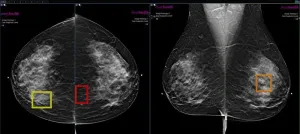

Women pay for AI to boost mammogram findings

2024-12-05

CHICAGO – More than a third of women across 10 health care practices chose to enroll in a self-pay, artificial intelligence (AI)-enhanced breast cancer screening program, and the women who enrolled were 21% more likely to have cancer detected, according to research being presented today at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

AI has shown great promise in mammography as a “second set of eyes” for radiologists providing decision support, risk prediction and other benefits. Despite its promise, AI is not yet reimbursed by insurance, which likely is slowing its adoption ...

Gene editing and plant domestication essential to protect food supplies in a worsening climate, scientists say

2024-12-05

We all need to eat, but the impact of the climate crisis on our crops is throwing the world’s food supply into question. Modern crops, domesticated for high food yields and ease of harvesting, lack the genetic resources to respond to the climate crisis. Significant environmental stresses are reducing the amount of food produced, driving supplies down and prices up. We can’t sustainably take over more land for agriculture, so we need to change our crops—this time to adapt them to the world we have altered.

“Agriculture is highly vulnerable to climate change, and the intensity and frequency of extreme events is only going to increase,” said Prof Sergey ...

A film capacitor that can take the heat

2024-12-05

— By Michael Matz

The Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and several collaborating institutions have successfully demonstrated a machine-learning technique to accelerate discovery of materials for film capacitors — crucial components in electrification and renewable energy technologies. The technique was used to screen a library of nearly 50,000 chemical structures to identify a compound with record-breaking performance.

The other collaborators from University of Wisconsin–Madison, Scripps Research Institute, University of California, ...

New pathways to long-term memory formation

2024-12-05

Researchers from Max Planck Florida Institute for Neuroscience have discovered a new pathway to forming long-term memories in the brain. Their work suggests that long-term memory can form independently of short-term memory, a finding that opens exciting possibilities for understanding memory-related conditions.

A New Perspective on Memory Formation

Our brain works diligently to record our experiences into memories, creating representations of our daily events that stay with us for short time periods. Current scientific theories of memory formation suggest that short-term memories are stored in what we can imagine as a temporary art exhibition in our ...

Iberian Neolithic societies had a deep knowledge of archery techniques and materials

2024-12-05

• A research team led by the UAB has made exceptional discoveries on prehistoric archery from the early Neolithic period, 7,000 years ago.

• The well organic preservation of the remains of the Cave of Los Murciélagos in Albuñol, Granada, made it possible for scientists to identify the oldest bowstrings in Europe, which were made from the tendons of three animal species.

• The use of olive and reed wood and birch bark pitch in the making of arrows reveals an unprecedented degree of precision and technical mastery, as highlighted in the study, published in Scientific Reports. ...

Tyrannosaur teeth discovered in Bexhill-on-Sea with help of retired quarryman

2024-12-05

EMBARGOED: NOT FOR RELEASE UNTIL 00.01 UK TIME ON THURSDAY 5 DECEMBER 2024

Tyrannosaur teeth discovered in Bexhill-on-Sea with help of retired quarryman

Spinosaur and Velociraptor-like predators also roamed East Sussex 135 million years ago

Research led by the University of Southampton has revealed that several groups of meat-eating dinosaur stalked the Bexhill-on-Sea region of coastal East Sussex 135 million years ago.

The study, published today [5 December 2024] in Papers in Palaeontology, has discovered a whole community of predators belonging to different ...

Women with ovarian removal have unique risk and resilience factors for Alzheimer disease

2024-12-05

TORONTO - New research published by a team of researchers from the University of Toronto in collaboration with colleagues from the University of Alberta has found that women who have had both ovaries surgically removed before the age of 50 and carry a variant of the apolipoprotein gene, the APOE4 allele, are at high risk of late-life Alzheimer disease (AD). Use of hormone therapy mitigates this risk.

Why does this matter?

By 2050, Alzheimer’s disease is projected to affect 12.7 million individuals 65 and older with women comprising two-thirds of that number. It is still unclear why Alzheimer’s disease is more prevalent in women than in men, but it may have to do with ...

Researchers discover new neurons that suppress food intake

2024-12-05

BALTIMORE, Dec. 5, 2024: Obesity affects a staggering 40 percent of adults and 20 percent of children in the United States. While some new popular therapies are helping to tackle the epidemic of obesity, there is still so much that researchers do not understand about the brain-body connection that regulates appetite. Now, researchers have discovered a previously unknown population of neurons in the hypothalamus that regulate food intake and could be a promising new target for obesity drugs.

In a study published in the Dec. 5 issue of Nature, a team of researchers from the Laboratory ...

Deforestation reduces malaria bed nets’ effectiveness

2024-12-05

When a forest is lost to development, some effects are obvious. Stumps and mud puddles across the landscape, a plowed field or houses a year after that. But deforestation isn’t just a loss of trees; it’s a loss of the countless benefits that forests provide—one of which is control of disease.

Now, a startling new global study shows that a widespread malaria-fighting strategy—bed nets—becomes less effective as deforestation rises. The research underscores how important a healthy environment can be for human health.

Insecticide-treated ...