(Press-News.org) New observations from the James Webb Space Telescope suggest that a new feature in the universe—not a flaw in telescope measurements—may be behind the decadelong mystery of why the universe is expanding faster today than it did in its infancy billions of years ago.

The new data confirms Hubble Space Telescope measurements of distances between nearby stars and galaxies, offering a crucial cross-check to address the mismatch in measurements of the universe’s mysterious expansion. Known as the Hubble tension, the discrepancy remains unexplained even by the best cosmology models.

“The discrepancy between the observed expansion rate of the universe and the predictions of the standard model suggests that our understanding of the universe may be incomplete. With two NASA flagship telescopes now confirming each other’s findings, we must take this [Hubble tension] problem very seriously—it’s a challenge but also an incredible opportunity to learn more about our universe,’’ said Nobel laureate and lead author Adam Riess, a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor and Thomas J. Barber Professor of Physics and Astronomy at Johns Hopkins University.

Published in The Astrophysical Journal, the research builds on Riess’ Nobel Prize–winning discovery that the universe’s expansion is accelerating owing to a mysterious “dark energy” permeating vast stretches of space between stars and galaxies.

Riess’ team used the largest sample of Webb data collected over its first two years in space to verify the Hubble telescope’s measure of the expansion rate of the universe, a number known as the Hubble constant. They used three different methods to measure distances to galaxies that hosted supernovae, focusing on distances previously gauged by the Hubble telescope and known to produce the most precise “local” measurements of this number. Observations from both telescopes aligned closely, revealing that Hubble’s measurements are accurate and ruling out an inaccuracy large enough to attribute the tension to an error by Hubble.

Still, the Hubble constant remains a puzzle because measurements based on telescope observations of the present universe produce higher values compared to projections made using the “standard model of cosmology,” a widely accepted framework of how the universe works calibrated with data of cosmic microwave background, the faint radiation left over from the big bang.

While the standard model yields a Hubble constant of about 67-68 kilometers per second per megaparsec, measurements based on telescope observations regularly give a higher value of 70 to 76, with a mean of 73 km/s/Mpc. This mismatch has perplexed cosmologists for over a decade because a 5-6 km/s/Mpc difference is too large to be explained simply by flaws in measurement or observational technique. (Megaparsecs are huge distances. Each is 3.26 million light-years, and a light-year is the distance light travels in one year: 9.4 trillion kilometers, or 5.8 trillion miles.)

Since Webb’s new data rules out significant biases in Hubble’s measurements, the Hubble tension may stem from unknown factors or gaps in cosmologists’ understanding of physics yet to be discovered, Riess’ team reports.

“The Webb data is like looking at the universe in high definition for the first time and really improves the signal-to-noise of the measurements,’’ said Siyang Li, a graduate student working at Johns Hopkins University on the study.

The new study covered roughly a third of Hubble’s full galaxy sample, using the known distance to a galaxy called NGC 4258 as a reference point. Despite the smaller dataset, the team achieved impressive precision, showing differences between measurements of under 2%—far smaller than the approximately 8-9% size of the Hubble tension discrepancy.

In addition to their analysis of pulsating stars called Cepheid variables, the gold standard for measuring cosmic distances, the team cross-checked measurements based on carbon-rich stars and the brightest red giants across the same galaxies. All galaxies observed by Webb together with their supernovae yielded a Hubble constant of 72.6 km/s/Mpc, nearly identical to the value of 72.8 km/s/Mpc found by Hubble for the very same galaxies.

The study included samples of Webb data from two groups that work independently to refine the Hubble constant, one from Riess’ SH0ES team (Supernova, H0, for the Equation of State of Dark Energy) and one from the Carnegie-Chicago Hubble Program, as well as from other teams. The combined measurements make for the most precise determination yet about the accuracy of the distances measured using the Hubble Telescope Cepheid stars, which are fundamental for determining the Hubble constant.

Although the Hubble constant does not have a practical effect on the solar system, Earth, or daily life, it reveals the evolution of the universe at extremely large scales, with vast areas of space itself stretching and pushing distant galaxies away from one another like raisins in rising dough. It is a key value scientists use to map the structure of the universe, deepen their understanding of its state 13-14 billion years after the big bang, and calculate other fundamental aspects of the cosmos.

Resolving the Hubble tension could reveal new insights into more discrepancies with the standard cosmological model that have come to light in recent years, said Marc Kamionkowski, a Johns Hopkins cosmologist who helped calculate the Hubble constant and has recently helped develop a possible new explanation for the tension.

The standard model explains the evolution of galaxies, cosmic microwave background from the big bang, the abundances of chemical elements in the universe, and many other key observations based on the known laws of physics. However, it does not fully explain the nature of dark matter and dark energy, mysterious components of the universe estimated to be responsible for 96% of its makeup and accelerated expansion.

“One possible explanation for the Hubble tension would be if there was something missing in our understanding of the early universe, such as a new component of matter—early dark energy—that gave the universe an unexpected kick after the big bang,” said Kamionkowski, who was not involved in the new study. “And there are other ideas, like funny dark matter properties, exotic particles, changing electron mass, or primordial magnetic fields that may do the trick. Theorists have license to get pretty creative.”

Other authors are Dan Scolnic and Tianrui Wu of Duke University; Gagandeep S. Anand, Stefano Casertano, and Rachael Beaton of the Space Telescope Science Institute; Louise Breuval, Wenlong Yuan, Yukei S. Murakami, Graeme E. Addison, and Charles Bennett of Johns Hopkins University; Lucas M. Macri of NSF NOIRLab; Caroline D. Huang of The Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian; Saurabh Jha of Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey; Dillon Brout of Boston University; Richard I. Anderson of École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne; Alexei V. Filippenko of University of California, Berkeley; and Anthony Carr of University of Queensland, Brisbane.

This research is supported by Department of Energy grant DE-SC0010007, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Templeton Foundation, Sloan Foundation, JWST GO-1685 and GO-2875, HST GO-16744 and GO-17312, and the Christopher R. Redlich Fund.

END

Webb telescope’s largest study of universe expansion confirms challenge to cosmic theory

The findings support Hubble’s expansion rate measurements

2024-12-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

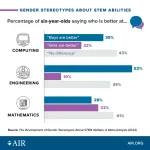

By age six, children think boys are better than girls at computing and engineering, new American Institutes for Research study shows

2024-12-09

Arlington, Va. – Children as young as age 6 develop gender stereotypes about computer science and engineering, viewing boys as more capable than girls, according to new results from an American Institutes for Research (AIR) study. However, math stereotypes are far less gendered, showing that young children do not view all science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields as the same.

These new findings come from the largest-ever study on children’s gender stereotypes about STEM and verbal abilities, based on data from 145,000 children across 33 nations, synthesizing more than 40 years of ...

Hair growth drug safe at low doses for breast cancer patients

2024-12-09

Hair loss during chemotherapy can cause enough distress for some women to lose self-confidence, which experts say may discourage them from seeking chemotherapy in the first place.

Oral minoxidil is a commonly prescribed treatment for hair loss. The drug is also the active ingredient in over-the-counter Rogaine. The prescription treatment is known, however, to dilate blood vessels, and experts worry that this could increase the heart-related side effects of chemotherapy and lead to chest pain, shortness of breath, or fluid buildup.

Now, a study in women with breast cancer suggests that low oral doses of minoxidil, taken during ...

Giving a gift? Better late than never, study finds

2024-12-09

COLUMBUS, Ohio – If you feel terrible about giving a late gift to a friend for Christmas or their birthday, a new study has good news for you.

Researchers found that recipients aren’t nearly as upset about getting a late gift as givers assume they will be.

“Go ahead and send that late gift, because it doesn’t seem to bother most people as much as givers fear,” said Cory Haltman, lead author of the study and doctoral student in marketing at The Ohio State University’s Fisher College of Business.

In a series of six studies, Haltman and his colleagues explored the mismatch between givers’ ...

Judging knots throws people for a loop

2024-12-09

We tie our shoes, we put on neckties, we wrestle with power cords. Yet despite deep familiarity with knots, most people cannot tell a weak knot from a strong one by looking at them, new Johns Hopkins University research finds.

Researchers showed people pictures of two knots and asked them to point to the strongest one. They couldn’t.

They showed people videos of each knot, where the knots spin slowly so they could get a good long look. They still failed.

People couldn’t even manage it ...

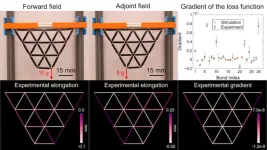

Not so simple machines: Cracking the code for materials that can learn

2024-12-09

It's easy to think that machine learning is a completely digital phenomenon, made possible by computers and algorithms that can mimic brain-like behaviors.

But the first machines were analog and now, a small but growing body of research is showing that mechanical systems are capable of learning, too. Physicists at the University of Michigan have provided the latest entry into that field of work.

The U-M team of Shuaifeng Li and Xiaoming Mao devised an algorithm that provides a mathematical framework for how learning works in lattices called ...

Finding the weak points: New method to prevent train delay cascades

2024-12-09

[Vienna, 09.12.2024] —Train delays are not only a common frustration for passengers but can also lead to significant economic losses, especially when they cascade through the railway network. When a train is delayed, it often triggers a chain reaction, turning minor issues into widespread delays across the system. This can be costly. A report from the Association of American Railroads (AAR) indicates that a nationwide rail disruption in the US could cost the economy over $2 billion per day. Therefore, the pressing question for railway operators is: How to manage the cascading effect of delays efficiently ...

New AI cracks complex engineering problems faster than supercomputers

2024-12-09

Modeling how cars deform in a crash, how spacecraft responds to extreme environments, or how bridges resist stress could be made thousands of times faster thanks to new artificial intelligence that enables personal computers to solve massive math problems that generally require supercomputers.

The new AI framework is a generic approach that can quickly predict solutions to pervasive and time-consuming math equations needed to create models of how fluids or electrical currents propagate through different ...

Existing EV batteries may last up to 40% longer than expected

2024-12-09

The batteries of electric vehicles subject to the normal use of real world drivers - like heavy traffic, long highway trips, short city trips, and mostly being parked - could last about a third longer than researchers have generally forecast, according to a new study by scientists working in the SLAC-Stanford Battery. Center, a joint center between Stanford University's Precourt Institute for Energy and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, This suggests that the owner of a typical EV may not need to replace the expensive battery pack or buy a new car for several additional years.

Almost always, battery scientists and engineers have tested ...

Breakthrough AI model can translate the language of plant life

2024-12-09

A pioneering Artificial Intelligence (AI) powered model able to understand the sequences and structure patterns that make up the genetic “language” of plants, has been launched by a research collaboration.

Plant RNA-FM, believed to be the first AI model of its kind, has been developed by a collaboration between plant researchers at the John Innes Centre and computer scientists at the University of Exeter.

The model, say its creators, is a smart technological breakthrough that can drive discovery and innovation in plant science and potentially across the study of invertebrates ...

MASH discovery redefines subtypes with distinct risks: shaping the future of fatty liver disease treatment

2024-12-09

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), formerly referred to as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), impacts roughly 30% of the global adult population. The disease spans from benign fat accumulation in the liver (steatosis) to its more severe form, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH, formerly nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or NASH). MASH represents a dangerous progression, with the potential to cause cirrhosis, liver cancer, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Despite ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Power in motion: transforming energy harvesting with gyroscopes

Ketamine high NOT related to treatment success for people with alcohol problems, study finds

1 in 6 Medicare beneficiaries depend on telehealth for key medical care

Maps can encourage home radon testing in the right settings

Exploring the link between hearing loss and cognitive decline

Machine learning tool can predict serious transplant complications months earlier

Prevalence of over-the-counter and prescription medication use in the US

US child mental health care need, unmet needs, and difficulty accessing services

Incidental rotator cuff abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging

Sensing local fibers in pancreatic tumors, cancer cells ‘choose’ to either grow or tolerate treatment

Barriers to mental health care leave many children behind, new data cautions

Cancer and inflammation: immunologic interplay, translational advances, and clinical strategies

Bioactive polyphenolic compounds and in vitro anti-degenerative property-based pharmacological propensities of some promising germplasms of Amaranthus hypochondriacus L.

AI-powered companionship: PolyU interfaculty scholar harnesses music and empathetic speech in robots to combat loneliness

Antarctica sits above Earth’s strongest “gravity hole.” Now we know how it got that way

Haircare products made with botanicals protects strands, adds shine

Enhanced pulmonary nodule detection and classification using artificial intelligence on LIDC-IDRI data

Using NBA, study finds that pay differences among top performers can erode cooperation

Korea University, Stanford University, and IESGA launch Water Sustainability Index to combat ESG greenwashing

Molecular glue discovery: large scale instead of lucky strike

Insulin resistance predictor highlights cancer connection

Explaining next-generation solar cells

Slippery ions create a smoother path to blue energy

Magnetic resonance imaging opens the door to better treatments for underdiagnosed atypical Parkinsonisms

National poll finds gaps in community preparedness for teen cardiac emergencies

One strategy to block both drug-resistant bacteria and influenza: new broad-spectrum infection prevention approach validated

Survey: 3 in 4 skip physical therapy homework, stunting progress

College students who spend hours on social media are more likely to be lonely – national US study

Evidence behind intermittent fasting for weight loss fails to match hype

How AI tools like DeepSeek are transforming emotional and mental health care of Chinese youth

[Press-News.org] Webb telescope’s largest study of universe expansion confirms challenge to cosmic theoryThe findings support Hubble’s expansion rate measurements