(Press-News.org) Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah (the U) has joined other institutions in an innovative clinical trials program designed to match patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) with a clinical trial specifically designed for the genetic signature of their disease. Sponsored by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the myeloMATCH program aims to improve precision medicine, the use of therapies based on the unique makeup of an individual’s cancer. This program is potentially a pivotal advance in personalized cancer care.

Paul Shami, MD, investigator at Huntsman Cancer Institute and professor of medicine in the Division of Hematology and Hematologic Malignancies at the U, is one of the principal investigators involved in the myeloMATCH program.

“For a long time, we had just one aggressive chemotherapy treatment program for AML. In the past few years, we have evolved from the one size fits all model to where we have many treatment options,” says Shami. “To be able to put those options within a rational, scientifically designed clinical trials program is exciting and will hopefully move the field forward.”

Patients in the myeloMATCH program start by undergoing a bone marrow biopsy for diagnosis and screening. Depending on the genetic signature of their disease, they are assigned different trials specifically designed for their disease type. Throughout their journey in myeloMATCH, patients are assigned to different tiers of treatment depending on their response to therapy.

One important aspect of myeloMATCH is the use of groundbreaking technology to detect very low levels of disease—known as measurable residual disease (MRD).

“Not too long ago, a patient would be in remission, and a bone marrow biopsy would look clear under the microscope. But if we use these very sensitive tools to look for very, very low levels of disease, results can be different. Even that low level of residual disease has a negative prognostic impact,” says Shami. “But this type of molecular evaluation is not available everywhere, and myeloMATCH provides a systematic strategy to use MRD for treatment assignment.”

AML is a rare type of blood cancer, affecting about 20,000 patients per year in the U.S. MDS is a disease that leads to failure of the bone marrow and a drop in the number of blood cells. MDS can sometimes progress to AML. According to the National Cancer Institute, the five-year survival rate of AML among adults is just 31%. The average age of diagnosis is 69 years old.

“The myeloMATCH program gives us more treatment options to offer patients, including older or frail patients who would not be good candidates for aggressive chemotherapy, let alone a bone marrow transplant,” says Shami.

The initiative is designed to harness the scientific resources of the NCI’s National Clinical Trials Network, which supports clinical trials at over 2,000 sites nationally. The network is made up of several cooperative groups.

The myeloMATCH program combines the resources of the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology, ECOG-ACRIN, and SWOG. The Canadian Cancer Trials Group is also participating.

The NCI funds myeloMATCH, as well as the other precision medicine initiatives. The Huntsman Cancer Institute research described in this release is supported by the National Institutes of Health/NCI including P30 CA042014, and Huntsman Cancer Foundation.

About Huntsman Cancer Institue at the University of Utah

Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah is the National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center for Utah, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, and Wyoming. With a legacy of innovative cancer research, groundbreaking discoveries, and world-class patient care, we are transforming the way cancer is understood, prevented, diagnosed, treated, and survived. Huntsman Cancer Institute focuses on delivering the most advanced cancer healing and prevention through scientific breakthroughs and cutting-edge technology to advance cancer treatments of the future beyond the standard of care today. We have more than 300 open clinical trials and 250 research teams studying cancer. More genes for inherited cancers have been discovered at Huntsman Cancer Institute than at any other cancer center. Our scientists are world-renowned for understanding how cancer begins and using that knowledge to develop innovative approaches to treat each patient’s unique disease. Huntsman Cancer Institute was founded by Jon M. and Karen Huntsman.

END

Partnership advances targeted therapies for blood cancers

2024-12-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How loss of urban trees affects education outcomes

2024-12-17

It’s well established that urban tree cover provides numerous environmental and psychological benefits to city dwellers. Urban trees may also bolster education outcomes and their loss could disproportionately affect students from low-income families, according to new research by University of Utah social scientists.

Economics professor Alberto Garcia looked at changes in school attendance and standardized test scores at schools in the Chicago metropolitan region over the decade after a non-native ...

New virtual reality-tested system shows promise in aiding navigation of people with blindness or low vision

2024-12-17

A new study offers hope for people who are blind or have low vision (pBLV) through an innovative navigation system that was tested using virtual reality. The system, which combines vibrational and sound feedback, aims to help users navigate complex real-world environments more safely and effectively.

The research from NYU Tandon School of Engineering, published in JMIR Rehabilitation and Assistive Technology, advances work from John-Ross Rizzo, Maurizio Porfiri and colleagues toward developing a first-of-its-kind ...

Brain cells remain healthy after a month on the International Space Station, but mature faster than brain cells on Earth

2024-12-17

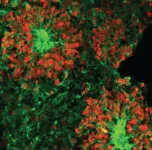

LA JOLLA, CA—Microgravity is known to alter the muscles, bones, the immune system and cognition, but little is known about its specific impact on the brain. To discover how brain cells respond to microgravity, Scripps Research scientists, in collaboration with the New York Stem Cell Foundation, sent tiny clumps of stem-cell derived brain cells called “organoids” to the International Space Station (ISS).

Surprisingly, the organoids were still healthy when they returned from orbit a month later, but the cells had matured faster compared ...

NIH grant funds study of cerebral small vessel disease

2024-12-17

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have been awarded $7.5 million from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to investigate a form of dementia caused by cerebral small vessel disease, the second-leading cause of dementia after Alzheimer’s disease.

The grant funds the Vascular Contributions to Cognitive Impairment and Dementia (VCID) Center, which is a National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke “Center Without Walls” initiative that will coordinate researchers at six sites across ...

Paranoia may be, in part, a visual problem

2024-12-17

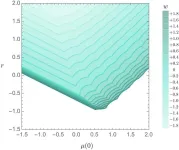

New Haven, Conn. — Could complex beliefs like paranoia have roots in something as basic as vision? A new Yale study finds evidence that they might.

When completing a visual perception task, in which participants had to identify whether one moving dot was chasing another moving dot, those with greater tendencies toward paranoid thinking (believing others intend them harm) and teleological thinking (ascribing excessive meaning and purpose to events) performed worse than their counterparts, the study found. Those individuals more often — and confidently — claimed one dot was chasing the other when it wasn’t.

The findings, published Dec. 17 in ...

The high cost of carbon

2024-12-17

The social cost of carbon — an important figure that global policymakers use to analyze the benefits of climate and energy policies — is too low, according to a study led by the University of California, Davis.

The study, published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), shows that current estimates for the social cost of carbon, or SCC, fail to adequately represent important channels by which climate change could affect human welfare. When included, the SCC increases to just over $280 per ton of CO2 emitted in 2020 — more than double the ...

This mysterious plant fossil belongs to a family that no longer exists

2024-12-17

In 1969, fossilized leaves of the species Othniophyton elongatum — which translates to “alien plant” — were identified in eastern Utah. Initially, scientists theorized the extinct species may have belonged to the ginseng family (Araliaceae). However, a case once closed is now being revisited. New fossil specimens show that Othniophyton elongatum is even stranger than scientists first thought.

Steven Manchester, curator of paleobotany at the Florida Museum of Natural History, has studied 47-million-year-old fossils from Utah for several years. While visiting ...

Physicists ‘bootstrap’ validity of string theory

2024-12-17

String theory, conceptualized more than 50 years ago as a framework to explain the formation of matter, remains elusive as a “provable” phenomenon. But a team of physicists has now taken a significant step forward in validating string theory by using an innovative mathematical method that points to its “inevitability.”

String theory posits that the most basic building blocks of nature are not particles, but, rather, one-dimensional vibrating strings that move at different frequencies ...

Parents’ childhood predicts future financial support for children’s education

2024-12-17

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Childhood circumstances, such as parental divorce or growing up poor, have been shown to influence health and other outcomes later in life. But does a person’s experiences in childhood also influence their future ability to provide financial support to their children?

According to a new study from a researcher from Penn State, parents who endured difficult childhoods provided less financial support to their children’s education such as college tuition compared to parents who experienced few or no disadvantages. Regardless of current socioeconomic ...

SFU study sheds new light on what causes long-term disability after a stroke and offers new path toward possible treatment

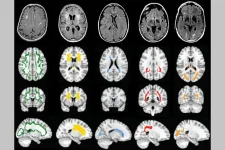

2024-12-17

A recent study from Simon Fraser University researchers has revealed how an overlooked type of indirect brain damage contributes to ongoing disability after a stroke.

The paper, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows how the thalamus – a sort of central networking hub that regulates functions such as language, memory, attention and movement – is affected months or years after a person has experienced a stroke, even though it was not directly damaged itself. The findings may lead to new therapies that could reduce the burden of chronic stroke, which remains one of the leading causes of disability in the world.

“Our ...