(Press-News.org) WOODS HOLE, Mass. -- Which microbes thrive below us in darkness – in gold mines, in aquifers, in deep boreholes in the seafloor – and how do they compare to the microbiomes that envelop the Earth’s surfaces, on land and sea?

The first global study to embrace this huge question, conducted at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), Woods Hole, reveals astonishingly high microbial diversity in some subsurface environments (up to 491 meters below the seafloor and up to 4375 m below ground).

This discovery points to vast, untapped, subsurface reservoirs of diversity for bioprospecting new compounds and medicinals, for understanding how cells adapt to extremely low-energy environments, and for illuminating the search for extraterrestrial life. Led by MBL Associate Scientist Emil Ruff, the study is published this week in Science Advances.

“It’s commonly assumed that the deeper you go below the Earth’s surface, the less energy is available, and the lower is the number of cells that can survive,” Ruff says. “Whereas the more energy present, the more diversity can be generated and maintained—as in tropical forests or coral reefs, where there’s lots of sun and warmth.

“But we show that in some subsurface environments, the diversity can easily rival, if not exceed, diversity at the surface. This is particularly true for marine environments and for microbes in the Archaea domain,” he says.

The sweeping study, which took 8 years to complete, is also one of the first to compare the marine vs. terrestrial realms in terms of microbial diversity and community composition.

“Look at plants and animals – very few of them are adapted to both the marine and terrestrial realms. One exception would be salmon,” Ruff says. “An interesting question is whether that is true for microbes as well?”

Yes, they discovered. Marine and terrestrial microbiomes differ greatly in composition, while their level of diversity is similar.

“So, this seems to be a universal ecological principle,” Ruff says. “There’s a very clear divide between life forms in the marine and in the terrestrial realms, not just in the surface, but also in the subsurface. The selective pressures are very different on land and in the sea, and they select for different organisms that have a hard time living in both realms.”

Life in the Deep, Dark, Slow Lane

“The first time scientists broadly realized there is a huge reservoir of microbes right under our feet, kilometers deep in rock and below the seafloor, was the mid-1990s,” Ruff says. Scientists now estimate between 50-80 percent of Earth’s microbial cells live in the subsurface, where energy availability can be orders of magnitude less than on the sunlit surface.

With this study, “we can now also appreciate that perhaps half the microbial diversity on Earth is in the subsurface,” Ruff says. “And it’s fascinating that, in these low-energy environments, life seems to be slowed down, sometimes to an absolute minimum. Based on estimates, some subsurface cells divide an average of once every 1,000 years. So, these microbes have completely different timescales of life, and we can potentially learn something about aging from them,” he says.

To survive in the subsurface, “it makes sense to be evolutionarily adapted to absolutely minimize your power and energy requirements and optimize every single part of your metabolism to be as energy efficient as possible,” Ruff says. “And we can also learn from that: How to be extremely efficient when you are working with next to nothing.”

If Mars or other planets had liquid water at some point in their histories – and there is evidence Mars did – then the rocky ecosystems 3 km below its surface would look very similar to those on Earth, Ruff says. “The energy would be very low; the organisms’ generation times would be very long. Understanding deep life on Earth could be a model for discovering if there was life on Mars, and if it has survived.”

How This Study Succeeded Where Others Could Not

Studies of microbial life in various pockets of the Earth’s surface and subsurface are not new or particularly scarce. But, Ruff says, the data from these studies was difficult, if not impossible, to synthesize due to inconsistencies in the research methodologies that different groups used.

In contrast, the present study began in 2016 when Ruff, then a postdoctoral researcher, attended a meeting of the Census of Deep Life, a pioneering effort to assess subsurface microbial life co-led by MBL Distinguished Senior Scientist Mitchell Sogin. For the Census, research groups all over the world sent subsurface samples to MBL, where scientists used the exact same routines to sequence and analyze the samples’ microbial DNA (MBL scientist Hilary Morrison led this part of the work). This provided, for the first time, a consistent dataset that could allow comparison across more than 1,000 samples from 50 marine and terrestrial ecosystems. And Ruff became intrigued by the idea of carrying out this large-scale comparison.

“For the first time, we could directly compare the microbiomes from, say, Great Lakes surface sediment with sediment from two kilometers below the seafloor,” Ruff says. “That’s where the beauty of this synthesis paper is coming from.”

Large-scale studies like this rely on many collaborators, most notably co-first author Isabella Hrabe de Angelis from the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, whose bioinformatics skills were critical to the study. Furthermore, additional scientists from the Marine Biological Laboratory (Mitchell Sogin, Hilary Morrison, Anna Shipunova, and Aleksey Morozov) contributed to this paper, as well as scientists from University of South Alabama, Oregon State University, ETH Zurich, University of Tennessee-Knoxville, University of Minnesota-Duluth, Dauphin Island Sea Laboratory, University of Toulon, Queen Mary University of London, Université Savoie Mont-Blanc, Michigan State University, University of Georgia, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, University of Duisburg-Essen, University of California-San Francisco, and Arva Intelligence.

END

Living in the deep, dark, slow lane: Insights from the first global appraisal of microbiomes in earth’s subsurface environments

2024-12-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

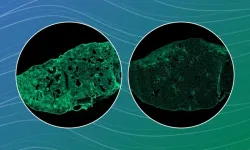

New discovery by Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine researchers provides hope in fighting drug-resistant malaria

2024-12-18

Malaria, caused by a parasite transmitted to humans through an infected mosquito’s bite, is a leading cause of illness and death worldwide.

Most susceptible are pregnant women, displaced people and children in developing countries, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Treating the disease is difficult because Plasmodium falciparum, the deadliest malaria parasite, is resistant to nearly all malaria medications.

But in a study published today in Science Advances, researchers at Case Western Reserve ...

What is metformin’s secret sauce?

2024-12-18

Leading diabetes drug lowers blood sugar by interfering with mitochondria

CHICAGO --- Millions of people take metformin, a Type 2 diabetes medication that lowers blood sugar. The “wonder drug” has also been shown to slow cancer growth, improve COVID outcomes and reduce inflammation. But until now, scientists have been unable to determine how, exactly, the drug works.

A new Northwestern Medicine study has provided direct evidence in mice that the drug reversibly cuts the cell’s ...

Researchers unlock craniopharyngioma growth mechanism and identify potential new therapy

2024-12-18

Chinese researchers recently revealed new insights on the growth of craniopharyngioma and identified a potential therapeutic treatment.

Their findings were published online in Science Translational Medicine on December 19.

Craniopharyngioma, a benign yet highly invasive tumor occurring along the hypothalamus-pituitary axis, presents a unique clinical challenge. Although nonmalignant, its proximity to critical brain structures often leads to severe endocrine and metabolic complications. The tumor can invade the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, resulting in endocrine dysfunction and metabolic disorders ...

Massive volcanic eruptions did not cause the extinction of dinosaurs

2024-12-18

Massive volcanic eruptions on the Indian peninsula have long been proposed as an alternative cause for the demise of the dinosaurs. This phase of active volcanism took place in a period just before the Earth was struck by a meteorite, 66 million years ago. The effect of these volcanic eruptions on the Earth’s climate has been topic of fierce scientific debates for decades. Now, climate scientists from Utrecht University and the University of Manchester show that, while the volcanism caused a temporary cold period, the effects had already worn off thousands of years before the meteorite impacted. The scientists therefore conclude that the meteorite impact was the ...

Common cough syrup ingredient shows promise in treating serious lung disease

2024-12-18

A common over-the-counter ingredient in many cough syrups may have a greater purpose for people suffering from lung fibrosis that is related to any number of serious health conditions.

Scientists from EMBL Heidelberg were part of a collaborative effort to discover an effective treatment for lung fibrosis and found that the best candidate may be one that is already available as a cough medicine around the world, dextromethorphan. The study was recently published in Science Translational Medicine and showed how dextromethorphan can impede ...

Improvement initiative increased well-being and reduced inefficiencies for surgical residents

2024-12-18

Researchers at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine have shown that a systemic approach to eliminating inefficiencies in surgical residency programs can reduce unnecessary work hours in the general residency program at UC San Diego. The approach—based on Lean methodology—can also positively impact the training and overall well-being of surgery residents. The results are published today in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).

“Our study shows ...

After lockdown, immune system reacts more strongly to viruses and bacteria

2024-12-18

Research from Radboud university medical center shows that the lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on people's immune response to microorganisms. During the lockdown, inflammation level in the body was low, but afterwards, the immune system reacted more intensely to viruses and bacteria. The results are now published in Frontiers of Immunology.

In this study, the researchers examined the effects of various health measures introduced during the pandemic, such as lockdowns and vaccinations. The study was conducted in a large cohort of people living with HIV, as well as in healthy individuals. The researchers ...

MD Anderson Research Highlights for December 18, 2024

2024-12-18

HOUSTON ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Research Highlights showcases the latest breakthroughs in cancer care, research and prevention. These advances are made possible through seamless collaboration between MD Anderson’s world-leading clinicians and scientists, bringing discoveries from the lab to the clinic and back.

Smoking cessation medications are safe and effective for people with depression

Individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) are more likely to smoke, leading to higher risks of nicotine addiction and early death from tobacco-related illnesses. To identify the best treatments for quitting, researchers led by George ...

Massive black hole in the early universe spotted taking a ‘nap’ after overeating

2024-12-18

Scientists have spotted a massive black hole in the early universe that is ‘napping’ after stuffing itself with too much food.

Like a bear gorging itself on salmon before hibernating for the winter, or a much-needed nap after Christmas dinner, this black hole has overeaten to the point that it is lying dormant in its host galaxy.

An international team of astronomers, led by the University of Cambridge, used the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope to detect this black hole in the early universe, just 800 million years after the Big Bang.

The black hole is huge – ...

Blight or benefit: how cellular neighbors shape the aging brain

2024-12-18

Much like plants in a thriving forest, certain cells in the brain create a nurturing environment, enhancing the health and resilience of their neighbors, while others promote stress and damage, akin to a noxious weed in an ecosystem.

A new study published in Nature on December 18, 2024, reveals these interactions playing out across the lifespan. It suggests local cellular interactions may profoundly influence brain aging — and offers fresh insights into how we might slow or even reverse the process.

“What was exciting to us was finding that some cells have a pro-aging effect on neighboring cells while others appear to have a rejuvenating effect on their neighbors,” ...