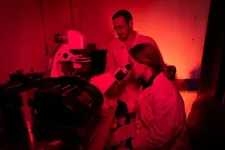

(Press-News.org) Humans and mice exposed to long-wavelength red light had lower rates of blood clots that can cause heart attacks, lung damage and strokes, according to research led by University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and UPMC surgeon-scientists and published today in the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

The findings, which need to be verified through clinical trials, have the potential to reduce blood clots in veins and arteries, which are leading causes of preventable death worldwide.

“The light we’re exposed to can change our biological processes and change our health,” said lead author Elizabeth Andraska, M.D., assistant professor of surgery in Pitt’s Trauma and Transfusion Medicine Research Center and vascular surgery resident at UPMC. “Our findings could lead to a relatively inexpensive therapy that would benefit millions of people.”

Scientists have long connected light exposure to health outcomes. The rising and setting of the sun underlies metabolism, hormone secretion, even the flow of blood, and heart attacks and stroke are more likely to happen in the morning hours than at night. Andraska and her colleagues wondered if light could have an impact on the blood clots that lead to these conditions.

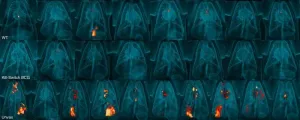

To test this idea, the team exposed mice to 12 hours of either red, blue or white light, followed by 12 hours of darkness, in a 72-hour cycle. They then looked for differences in blood clots between the groups. The mice exposed to red light had nearly five times fewer clots than the mice exposed to blue or white light. Activity, sleep, eating, weight and body temperature remained the same between the groups.

The team also analyzed existing data on more than 10,000 patients who had cataract surgery and received either conventional lenses that transmit the entire visible spectrum of light, or blue light-filtering lenses, which transmit about 50% less blue light. They discovered that cancer patients who received blue light-filtering lenses had lower risk of blood clots compared to their counterparts with conventional lenses. This is especially notable because cancer patients have nine times the risk of blood clots of non-cancer patients.

“These results are unraveling a fascinating mystery about how the light to which we’re exposed on a daily basis influences our body’s response to injury,” said senior author Matthew Neal, M.D., professor of surgery, Watson Fund in Surgery Chair and co-director of the Trauma and Transfusion Medicine Research Center at Pitt, and trauma surgeon at UPMC. “Our next steps are to figure out why, biologically, this is happening, and to test if exposing people at high risk for blood clots to more red light lowers that risk. Getting to the bottom of our discovery has the potential to massively reduce the number of deaths and disabilities caused by blood clots worldwide.”

The recently published study indicates that the optic pathway is key – light wavelength didn’t have any impact on blind mice, and shining light directly on blood also didn’t cause a change in clotting.

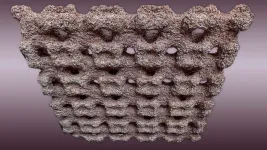

The team observed that red light exposure is associated with less inflammation and activation of the immune system. For example, red light-exposed mice had fewer neutrophil extracellular traps – aptly abbreviated as “NETs” – which are web-like structures made by immune cells to trap invading microorganisms. They also trap platelets, which can lead to clots.

The mice exposed to red light also had increased fatty acid production, which reduces platelet activation. Since platelets are essential to forming clots, this naturally leads to less clot formation.

Understanding how the red light is triggering changes that lower clotting risk could also put scientists on the track of better medications or therapies that could be more potent and convenient for patients than continuous red light exposure.

In preparation for clinical trials, the team is developing red light goggles to control the amount of light exposure study participants receive and investigating who may most benefit from red light

Additional authors on this research are Frederik Denorme, Ph.D., Robert Campbell, Ph.D., and Matthew R. Rosengart, M.D., all of Washington University in St. Louis; Christof Kaltenmeier, M.D., Aishwarrya Arivudainabi, Emily P. Mihalko, Ph.D., Mitchell Dyer, M.D., Gowtham K. Annarapu, Ph.D., Mohammadreza Zarisfi, M.D., Patricia Loughran, Ph.D., Mehves Ozel, M.D., Kelly Williamson, Ph.D., Roberto Mota-Alvidrez, M.D., Sruti Shiva, Ph.D., Susan Shea, Ph.D., and Richard A. Steinman, M.D., Ph.D., all of Pitt; and Kimberly Thomas, Ph.D., of Vitalant Research Institute.

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R35GM119526, K01AG059892, R01HL163019, R01GM147121, R01GM145674, T32HL98036 and S10OD028483, the University of Pittsburgh Center for Research Computing, National Center for Research Resources Shared Instrumentation grants 1S10OD016232-01, 1S10OD018210-01A1 and 1S10OD021505-01, American Heart Association 2021Post830138 award, and a Physician-Scientist Institutional Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

END

Red light linked to lowered risk of blood clots

2025-01-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Menarini Group and Insilico Medicine enter a second exclusive global license agreement for an AI discovered preclinical asset targeting high unmet needs in oncology

2025-01-10

This is the second asset Menarini Group has inlicensed from Insilico Medicine which was discovered through their generative AI platform, similar to the preclinical stage KAT6 inhibitor (MEN2312) licensed a year ago and which advanced rapidly into the clinical phase.

Under the agreement, Menarini Group will be granted global rights to develop and commercialize the asset. The deal includes a $20m upfront payment, and the combined value, including all development, regulatory, and commercial milestones, is over $550 million, followed by tiered royalties.

FLORENCE, Italy and CAMBRIDGE, Mass., January 10, 2025 : The Menarini Group ("Menarini"), ...

Climate fee on food could effectively cut greenhouse gas emissions in agriculture while ensuring a social balance

2025-01-10

Agriculture accounts for 8 percent of all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Germany. “However, emissions within this sector, could be reduced by 22.5 percent or over 15 million tonnes of GHG annually, if the social cost of carbon were reflected in food prices,” says Julian Schaper, guest scientist at PIK and lead author of the study published in the journal Food Policy. In the Federal Climate Change Act passed in 2019, the government set itself the goal of reducing annual emissions from the current 62 million tonnes to 56 Mt GHG by 2030.

The social cost of carbon is an estimate of the economic damages that would result from emitting one additional tonne of carbon into the ...

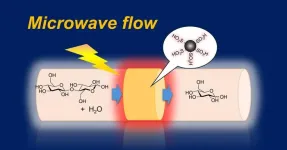

Harnessing microwave flow reaction to convert biomass into useful sugars

2025-01-10

Fukuoka, Japan—Researchers at Kyushu University have developed a device that combines a catalyst and microwave flow reaction to efficiently convert complex polysaccharides into simple monosaccharides. The device utilizes a continuous-flow hydrolysis process, where cellobiose—a disaccharide made from two glucose molecules—is passed through a sulfonated carbon catalyst that is heated using microwaves. The subsequent chemical reaction breaks down cellobiose into glucose. Their results were published in the journal ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering.

Converting biomass into ...

Unveiling the secrets of bone strength: the role of biglycan and decorin

2025-01-10

A recent study has uncovered the essential roles of two proteoglycans, biglycan and decorin, in maintaining bone mass, water retention, and bulk/in situ mechanical competence. Through the use of genetically modified mouse models, the research demonstrates that while biglycan plays a predominant role in preserving bone structure and toughness, decorin significantly contributes to the bone’s mechanical properties. These findings reveal how these proteins interact with water and other matrix components to regulate the mechanical ...

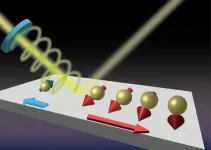

Revealing the “true colors” of a single-atom layer of metal alloys

2025-01-10

Researchers Ibuki Taniuchi, Ryota Akiyama, Rei Hobara, and Shuji Hasegawa of the University of Tokyo have demonstrated that the direction of the spin-polarized current can be restricted to only one direction in a single-atom layer of a thallium-lead alloys when irradiated at room temperature. The discovery defies conventions: single-atom layers have been thought to be almost completely transparent, in other words, negligibly absorbing or interacting with light. The one-directional flow of the current observed in this study makes possible functionality beyond ...

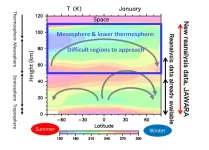

New data on atmosphere from Earth to the edge of space

2025-01-10

A team led by researchers at the University of Tokyo have created a dataset of the whole atmosphere, enabling new research to be conducted on previously difficult-to-study regions. Using a new data-assimilation system called JAGUAR-DAS, which combines numerical modeling with observational data, the team created a nearly 20-yearlong set of data spanning multiple levels of the atmosphere from ground level up to the lower edges of space. Being able to study the interactions of these layers vertically and around the globe could improve climate modeling and seasonal weather forecasting. There is also potential for interdisciplinary research between atmospheric scientists ...

Self-destructing vaccine offers enhanced protection against tuberculosis in monkeys

2025-01-10

PITTSBURGH, Jan. 10, 2025 – A self-destructing vaccine administered intravenously provides additional safety and protection against tuberculosis (TB) in macaque monkeys, suggests new University of Pittsburgh research published today in Nature Microbiology.

The in-built safety mechanisms circumvent the possibility of an accidental self-infection with weakened mycobacteria, offering a safe and effective way to combat the disease that was named as the deadliest of 2024 by the World Health Organization.

“Although the idea of intravenous vaccination with a live vaccine may sound scary, it was very ...

Feeding your good gut bacteria through fiber in diet may boost body against infections

2025-01-10

The group of bacteria called Enterobacteriaceae, including Klebsiella pneumoniae, Shigella, E.coli and others, is present at low levels as part of a healthy human gut microbiome. But at high levels - caused for example by increased inflammation in the body, or by eating contaminated food - these bugs can cause illness and disease. In extreme cases, too much Enterobacteriaceae in the gut can be life-threatening.

Researchers have used computational approaches including AI to analyse the gut microbiome composition of over 12,000 people across 45 countries from their stool samples. They found that a person’s microbiome ‘signature’ can predict ...

Sustainable building components create a good indoor climate

2025-01-10

Whether it’s the meeting room of an office building, the exhibition room of a museum or the waiting area of a government office, many people gather in such places, and quickly the air becomes thick. This is partly due to the increased humidity. Ventilation systems are commonly used in office and administrative buildings to dehumidify rooms and ensure a comfortable atmosphere. Mechanical dehumidification works reliably, but it costs energy and – depending on the electricity used – has a negative climate impact.

Against this backdrop, a team of researchers from ETH Zurich investigated a new approach to passive dehumidification of indoor spaces. Passive, in this context, means ...

High levels of disordered eating among young people linked to brain differences

2025-01-10

More than half of 23-year-olds in a European study show restrictive, emotional or uncontrolled eating behaviours, according to new research led by the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience (IoPPN) at King’s College London. Structural brain differences appear to play a role in the development of these eating habits.

The study, published in Nature Mental Health, investigates the links between genetics, brain structure and disordered eating behaviours in young people. Researchers found that the process of ‘brain maturation’, ...