(Press-News.org) Hamilton, ON (January 15, 2025) – Researchers at McMaster University have made an important discovery in the field of asthma research, identifying a new population of immune cells that may play a crucial role in the severity of asthma symptoms.

The study, published in Science Translational Medicine on Jan. 15, 2025, sheds light on the complex mechanisms behind severe asthma and opens new avenues for potential treatments.

Asthma is a chronic respiratory condition characterized by inflammation and narrowing of the airways, leading to difficulty breathing. Severe asthma, which affects up to 10 per cent of the general asthma population, is particularly challenging to treat due to its resistance to standard therapies.

“When you can’t breathe, nothing else matters,” says Roma Sehmi, senior and corresponding author of the paper and professor in the Department of Medicine at McMaster University. “Our Hamilton-based group has been world leaders in evaluating the type of inflammation in the airways using methods developed to sample and examine sputum. We sought to better understand the mechanisms behind severe asthma so that we can better treat these patients.”

The research team recruited patients from St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton and carried out experimental work in laboratories within McMaster University and the Firestone Institute for Respiratory Health (FIRH), a joint McMaster University-St. Joseph’s research institute.

Researchers explored a unique group of immune cells in the airways of people with severe asthma. The cells, called c-kit+IL-17A+ ILC2s, can be likened to chameleons; they can change their characteristics and have traits of two different types of immune cells. The study found that these "intermediate ILC2s" are linked to the presence of two types of cells that cause inflammation and make asthma worse (eosinophils and neutrophils).

The researchers discovered that people with severe asthma have these chameleon-like ILC2s that show markers of another cell type, ILC3, which are associated with a high number of neutrophils in the airways – often seen in difficult-to-treat severe asthma. The study also found growth factors that encourage the formation of these intermediate ILC2s, suggesting that controlling their levels could prevent too many neutrophils from accumulating and worsening asthma symptoms.

The ability of ILC2s to change and take on features of ILC3s in the airways of asthma patients is a new discovery. This finding gives new insights into what drives severe asthma and points to potential new treatment targets. By understanding the role of these intermediate ILC2s, researchers hope to develop better treatments for patients with severe asthma who don't respond well to current therapies.

“When asthma is associated with both eosinophils and neutrophils cells, individuals are generally less responsive to treatment with glucocorticosteroids – which are the mainstay of treatment for severe asthma. The findings from this research pave the way for discovering new therapeutic targets for difficult-to-treat asthma,” said Parameswaran Nair, co-corresponding author of the paper and professor in the Department of Medicine at McMaster University.

The study is the result of over a decade of collaborative research between Sehmi’s and Nair’s labs. The study involved contributions from several key researchers, including first author Xiaotian (Tim) Ju, who recently completed his PhD in Sehmi’s lab and is now a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland.

The study was funded in part by an educational grant from Hoffmann-La Roche and graduate scholarship awards from the MITACS accelerate program, Ontario Graduate Scholarship, and The Research Institute of St. Joe’s Hamilton.

For interviews please contact the authors directly:

Roma Sehmi, professor in the Department of Medicine at McMaster University

sehmir@mcmaster.ca

Parameswaran Nair, professor in the Department of Medicine at McMaster University

parames@mcmaster.ca

Photos of the authors can be found here.

More information, including a copy of the paper, can be found online at the Science Translational Medicine press package at eurekalert.org/press/medpak/.

For other inquiries: fhsmedia@mcmaster.ca

END

Researchers identify novel immune cells that may worsen asthma

2025-01-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

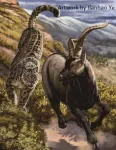

Conquest of Asia and Europe by snow leopards during the last Ice Ages uncovered

2025-01-15

The study, published in Science Advances, was led by researchers Qigao Jiangzuo, from Peking University, and Joan Madurell Malapeira, from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB).

Snow leopards (Panthera uncia) are in serious danger of extinction, with only about 4,000 specimens remaining. They are medium to large felids that live at high altitudes, over 2,000 meters above sea level, mainly in the Himalayas. Although their distinctive traits have long been recognized, the correlation between these ...

Researchers make comfortable materials that generate power when worn

2025-01-15

Researchers have demonstrated new wearable technologies that both generate electricity from human movement and improve the comfort of the technology for the people wearing them. The work stems from an advanced understanding of materials that increase comfort in textiles and produce electricity when they rub against another surface.

At issue are molecules called amphiphiles, which are often used in consumer products to reduce friction against human skin. For example, amphiphiles are often incorporated into diapers to prevent chafing.

“We set out to develop a model that would give us ...

Study finding Xenon gas could protect against Alzheimer’s disease leads to start of clinical trial

2025-01-15

Most treatments being pursued today to protect against Alzheimer’s disease focus on amyloid plaques and tau tangles that accumulate in the brain, but new research from Mass General Brigham and Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis points to a novel—and noble—approach: using Xenon gas. The study found that Xenon gas inhalation suppressed neuroinflammation, reduced brain atrophy, and increased protective neuronal states in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Results are published in Science Translational Medicine, and a phase 1 clinical trial of the treatment in healthy volunteers will begin in early 2025.

“It ...

Protein protects biological nitrogen fixation from oxidative stress

2025-01-15

A small helper for big tasks: an oxygen sensor protein protects the enzymatic machinery of biological nitrogen fixation from serious damage. Its use in biotechnology could help to reduce the use of synthetic fertiliser in agriculture in the future. A research team led by biochemist Prof. Dr Oliver Einsle from the Faculty of Chemistry and Pharmacy and the Centre for Biological Signalling Studies (BIOSS) at the University of Freiburg has discovered exactly how the so-called Shethna protein II works. The scientists used the newly established cryo-electron microscopy in Freiburg. ...

Three-quarters of medical facilities in Mariupol sustained damage during Russia’s siege of 2022

2025-01-15

Three-quarters of medical facilities in Mariupol sustained damage during Russia’s siege of 2022, with some evidence that the attacks may have been intentionally targeted, per study using satellite imagery.

####

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/globalpublichealth/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgph.0003950

Article Title: The effect of conflict on damage to medical facilities in Mariupol, Ukraine: a quasi-experimental study

Author Countries: Germany, United States

Funding: This work was supported ...

Snow leopard fossils clarify evolutionary history of species

2025-01-15

The snow leopard (Panthera uncia) is a large feline unique to the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and its surrounding areas. As the apex predator in the region, the snow leopard plays a crucial role in maintaining ecological stability. Its unique characteristics, coupled with its striking appearance, have made it a flagship species for conservation efforts aimed at protecting the ecosystem of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau.

Unfortunately, few snow leopard fossils have been found in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau region, particularly fossils from the Quaternary period. As a result, it’s unclear how snow leopards evolved their specialized adaptations to this environment.

On the one hand, molecular ...

Machine learning outperforms traditional statistical methods in addressing missing data in electronic health records

2025-01-15

Researchers from the National Institute of Health Data Science at Peking University and the Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Peking University People's Hospital have conducted a comprehensive systematic review evaluating strategies for addressing missing data in electronic health records (EHRs). Published in Health Data Science, the study highlights the growing importance of machine learning methods over traditional statistical approaches in managing missing data scenarios effectively.

Electronic health records have become a cornerstone in modern healthcare research, enabling analysis across clinical trials, treatment effectiveness studies, and ...

AI–guided lung ultrasound by nonexperts

2025-01-15

About The Study: In this multicenter validation study, trained health care professionals with artificial intelligence (AI) assistance achieved lung ultrasound images meeting diagnostic standards compared with lung ultrasound experts without AI. This technology could extend access to lung ultrasound to underserved areas lacking expert personnel.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Cristiana Baloescu, MD, MPH, email cristiana.baloescu@yale.edu.

To access the embargoed ...

Prevalence of and inequities in poor mental health across 3 US surveys

2025-01-15

About The Study: This survey study documents increasingly prevalent poor mental health from 2011 to 2022 across multiple U.S. health surveys, with notable prevalence differences in Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and National Survey on Drug Use and Health vs National Health Interview Survey. Inequities in these outcomes by age, sex, and racial and ethnic group were often sizeable and changed over time in distinct ways, consistent with findings in prior literature.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding ...

Association between surgeon stress and major surgical complications

2025-01-15

About The Study: In this cohort study including 38 attending surgeons and 793 patients, increased surgeon stress at the beginning of a procedure was associated with improved clinical patient outcomes. The results are illustrative of the complex relationship between physiological stress and performance, identify a novel association between measurable surgeon human factors and patient outcomes, and may highlight opportunities to improve patient care.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Jake Awtry, MD, email jawtry@bwh.harvard.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media ...