(Press-News.org) EUGENE, Ore. — Jan. 21, 2025 — Increased exposure to glyphosate, one of the most widely used herbicides in the United States and much of the world, harms infant health in U.S. agricultural counties, according to a new study by two University of Oregon economists.

In a paper published Jan. 14 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Emmett Reynier and Edward Rubin showed that a dramatic increase in the use of glyphosate in U.S. counties most suitable for genetically engineered crops lowered birthweights and gestation, the number of weeks from conception to birth.

They note that because pre-term births, on average, cost an estimated $82,000 in additional medical, educational and other expenses compared to a full-term birth, the national economic impact of the infant health effects translates to between $750 million and $1.1 billion in annual expenses. It does not include other potential health costs.

Reynier is a doctoral candidate in economics whose work is supported by a research fellowship with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Rubin is an environmental economist and assistant professor in the Department of Economics.

The EPA first approved glyphosate for use as an herbicide in the United States in 1974. Federal law requires such decisions to be reviewed every 15 years. In 2020, the agency determined that, if used according to label directions, glyphosate poses no risks to human health. The EPA also found that the herbicide is unlikely to cause cancer in humans.

In 2022, those findings were challenged in court and voided by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit. They are still under review.

Glyphosate kills plants that are not genetically modified to withstand the herbicide. Farmers can use it to kill weeds in fields planted with crops such as genetically modified corn, soybeans and cotton, which were first permitted for agricultural use in 1996. Since the introduction of genetically modified crops, annual glyphosate use in the U.S. has increased about 750 percent, according to a report from the U.S. Geological Survey.

Reynier and Rubin jointly planned their study to establish a more rigorous basis for understanding the effects of glyphosate on human health.

“We had heard some pretty broad claims about the effects of pesticides on health that seemed to be based more on correlations than on causal effects,” Reynier said. “We know people are concerned, and we wanted to make sure we were looking at this rigorously.”

In their study, the researchers evaluated human health effects using three types of existing data for rural U.S. counties: genetically modified crop suitability, historical pesticide applications and birth records.

From the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural Organization, they gathered data on crop suitability as determined by soils and climate. They used that data to rate agricultural counties on their suitability for raising genetically modified corn, cotton and soybeans. Counties highly suited to such crops, largely places where non-genetically modified versions of these crops were already grown, saw significantly larger increases in glyphosate use after 1996.

Data on births came from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rubin and Reynier selected a set of more than 9 million birth records in rural counties from 1990 to 2013. All the data were anonymous. Identifying information, such as the precise locations of crop fields and birth parents’ homes, was not included.

“By using the mother’s county, we matched the infant to the glyphosate exposure estimate. And then we asked how much birthweight changed in the higher-suitability counties versus lower-suitability counties,” said Rubin.

Prior to 1996, the data show that trends in two birth outcomes, birthweight and gestation, remained quite similar in counties less and more suitable for genetically modified crops. However, after 1996 infant health deteriorated sharply in counties more suitable for those crops relative to less suitable counties. Rubin and Reynier attribute that relative deterioration to the change in glyphosate use caused by the introduction of genetically modified seeds.

The researchers controlled for any unobserved factors that might have affected health before and after birth from year to year or across counties.

The results imply that at average levels of glyphosate exposure, average gestation was reduced by one day and average birthweight was reduced by 23-32 grams, about 1 ounce.

However, they also found that the changes did not affect all births equally. By considering how shorter gestation and reduced birthweight were spread out across all births, they found that glyphosate’s effects were largest among babies with the lowest expected birthweight.

“What this means is that, for whatever reason, if an infant is expected to be at the very low birthweight end of the scale, then glyphosate exposure could affect you more,” Rubin said. “It’s like being sick and then getting hit with another illness. You’re more vulnerable.”

Combined with other recent work, the findings challenge the prevailing regulatory position that genetically engineered crops and their associated agricultural practices are safe — and even beneficial — for health, Rubin and Reynier wrote.

“I think something has to change,” Rubin said. “Regulators could admit that glyphosate exposure presents some concerns for human health. There’s mounting evidence that it could be detrimental.”

In addition, he said, there could be greater monitoring of glyphosate use and exposure as well as human health.

“We’re still not tracking it in water. We’re not tracking it when it’s applied,” he said. “It does seem like, even if we’re not ready to regulate it in a serious way, we could monitor it.”

— By Nick Houtman, for University Communications

This project was supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the Water Economics Center, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and EPA.

About the University of Oregon College of Arts and Sciences

The University of Oregon College of Arts and Sciences supports the UO’s mission and shapes its identity as a comprehensive research university. With disciplines in humanities and social and natural sciences, the College of Arts and Sciences serves approximately two-thirds of all UO students. The College of Arts and Sciences faculty includes some of the world’s most accomplished researchers, and the more than $75 million in sponsored research activity of the faculty underpins the UO’s status as a Carnegie Research I institution and its membership in the Association of American Universities.

END

Study links popular herbicide to problems with infant health

Work by University of Oregon economists suggests exposure to glyphosate can cause low birthweight, early birth

2025-01-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Why you should (not) get a dog: the pros and cons of dog ownership

2025-01-21

Are dogs really the key to better health and a happier life? In this new study, dog owners were invited to describe the biggest benefits and challenges of dog ownership. The commitments and responsibilities of having a dog were found to be both a joy and a burden, highlighting the importance of making a conscious adoption choice.

The pet dog population has been growing worldwide. Often benefiting from good press in mainstream media, dog ownership is generally assumed to improve human lives, providing companionship and boosting well-being. While bringing a dog into the family does come with ...

After millennia as carbon dioxide sink, more than one-third of Arctic-boreal region is now a source

2025-01-21

After millennia as a carbon deep-freezer for the planet, regional hotspots and increasingly frequent wildfires in the northern latitudes have nearly canceled out that critical storage capacity in the permafrost region, according to a new study published in Nature Climate Change.

An international team led by Woodwell Climate Research Center found that a third (34 percent) of the Arctic-boreal zone (ABZ)—the treeless tundra, boreal forests, and wetlands that make up Earth’s northern latitudes—is now a source of carbon to the atmosphere. That balance sheet is made up of carbon dioxide (CO₂) uptake from plant photosynthesis and CO₂ ...

The reversal of lipoprotein alterations in patients with ischaemic stroke offers new perspectives for cardiovascular disease research and management

2025-01-21

A study recently published by researchers from the Sant Pau Research Institute (IR Sant Pau) and the Stroke Unit of Sant Pau Hospital in the Journal of Lipid Research provides new evidence on the essential role of the qualitative properties of lipoproteins, such as LDL and HDL, in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases, including ischaemic stroke. The findings underscore the importance of going beyond traditional quantitative cholesterol levels to evaluate the risk of these pathologies.

Dr ...

Early diagnosis of bladder cancer, now conveniently at home

2025-01-21

Bladder cancer has a cure rate of over 90% when detected early, but it has a high recurrence rate of 70%, necessitating continuous monitoring. Late detection often requires major surgeries such as bladder removal followed by artificial bladder implantation or the use of a urine pouch, significantly lowering the patient’s quality of life. However, existing urine test kits have low sensitivity, and cystoscopy, which involves inserting a catheter into the urethra for internal bladder examination, is both painful and burdensome. This highlights the urgent need for a simple yet accurate diagnostic technology for patients.

The research team led by Dr. Youngdo Jeong of the Center for Advanced ...

People who are autistic and transgender/gender diverse have poorer health and health care

2025-01-21

Researchers at the Autism Research Centre at Cambridge University found that these individuals also report experiencing lower quality healthcare than both autistic and non-autistic people whose gender identity matches their sex assigned at birth (cisgender).

The findings have important implications for the healthcare and support of autistic transgender/gender diverse (TGD) individuals. This is the first large-scale study on the experiences of autistic TGD people and the results are published today in Molecular Autism.

Previous research suggests that both autistic people and TGD people separately have poorer healthcare experiences ...

Gene classifier tests for prostate cancer may influence treatment decisions despite lack of evidence for long-term outcomes

2025-01-20

Embargoed for release until 5:00 p.m. ET on Monday 20 January 2025

@Annalsofim

Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf of the organization they represent. ...

KERI, overcomes the biggest challenge of the lithium–sulfur battery, the core of UAM

2025-01-20

Dr. Park Jun-woo's team at KERI's Next Generation Battery Research Center has overcome a major obstacle to the commercialization of next-generation lithium–sulfur batteries and successfully developed large-area, high-capacity prototypes.

The lithium–sulfur battery, composed of sulfur as the cathode (+) and lithium metal as the anode (-), has a theoretical energy density more than eight times that of lithium-ion batteries, demonstrating significant potential. Additionally, it uses abundant sulfur (S) instead of expensive rare earth elements, making it cost-effective and environmentally ...

In chimpanzees, peeing is contagious

2025-01-20

A new study reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on January 20 is the first to describe a phenomenon researchers refer to as “contagious urinations.” The study in 20 captive chimpanzees living at the Kumamoto Sanctuary in Japan shows that, when one chimp pees, others are more likely to follow.

“In humans, urinating together can be seen as a social phenomenon,” says Ena Onishi of Kyoto University.

“An Italian proverb states, ‘Whoever doesn’t pee in company is either a thief or a spy’ (Chi non piscia in compagnia o è ...

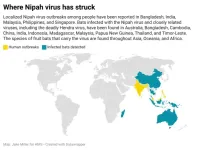

Scientists uncover structure of critical component in deadly Nipah virus

2025-01-20

Scientists at Harvard Medical School and Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine have mapped a critical component of the Nipah virus, a highly lethal bat-borne pathogen that has caused outbreaks in humans almost every year since it was identified in 1999.

The advance, described Jan. 20 in Cell, brings scientists a step closer to developing much-needed medicines. Currently, there are no vaccines to prevent or mitigate infection with the Nipah virus and no effective treatments for the disease ...

Study identifies benefits, risks linked to popular weight-loss drugs

2025-01-20

Demand for weight-loss medications sold under brand names such as Ozempic and Wegovy continues to surge, with a recent study reporting one in eight Americans has taken or is currently using the drugs to treat diabetes, heart disease or obesity.

Formally, these drugs are known as glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA) and include Mounjaro and Zepbound. Informally, media, patients and even some physicians have dubbed GLP-1 medications as “miracle drugs” because of the profound weight loss among users. While these health benefits are well established, information is sparse on the drugs’ effects across ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Study links popular herbicide to problems with infant healthWork by University of Oregon economists suggests exposure to glyphosate can cause low birthweight, early birth