(Press-News.org) Key takeaways

Globally, over 600 million people are infected with the skin-penetrating threadworm, Strongyloides stercoralis, mostly in tropical and subtropical regions with poor sanitation infrastructure.

Infections are treated with ivermectin, but some nematodes are starting to develop resistance to this first-line drug.

UCLA biologists have discovered that the nematodes respond differently to carbon dioxide at different stages in their life cycle, which could help scientists find ways to prevent or cure infections by targeting the CO2-sensing pathway.

In the United States, the most well-known skin-penetrating parasitic worm, called a nematode, is the hookworm. But globally, it is estimated that over 600 million people are infected with the skin-penetrating threadworm, also known as Strongyloides stercoralis. This species is found mostly in tropical and subtropical regions with poor sanitation infrastructure. Skin-penetrating nematodes are excreted in the feces of an infected host, and then enter the ground to wait for a new host. When they infect a new host, they can cause serious illnesses.

Currently, infections are treated with ivermectin, but some nematodes are starting to develop resistance to this first-line drug. New medications are needed, and UCLA neurobiologists might have just found a clue needed to inspire their design.

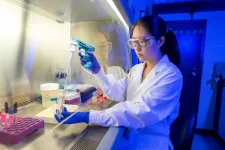

In a paper published in Current Biology, UCLA researchers report that S. stercoralis threadworms respond differently to carbon dioxide at different stages in their life cycle. They also identified a pair of neurons and a gene that detects CO2 in these parasites, and showed how to manipulate them for further research. Because CO2 is found abundantly in tissues such as the lungs and intestine, the discovery could help scientists find ways to prevent or cure infections by targeting the CO2-sensing pathway.

“Skin-penetrating nematodes encounter high CO2 concentrations throughout their life cycle, both in fecal and soil microenvironments and inside the host body,” said corresponding author and UCLA professor of microbiology, immunology and molecular genetics Elissa Hallem. “Our results suggest that responses to carbon dioxide play an important role in how these parasites interact with human hosts as they pass through the different stages of their life cycle and establish an infection.”

The threadworm infection cycle begins when immature larvae excreted in host poop develop into larvae. The infective larvae then crawl off the poop and into the soil to search for a host to infect. After finding a host and entering the host through the skin, the nematodes travel through the host’s body and are thought to pass through the lungs. They ultimately migrate to the small intestine, where they reside as parasitic adults and lay eggs. The larvae that hatch from these eggs are excreted, and the cycle begins again.

The UCLA researchers found that infective larvae are repelled by CO2, while noninfective larvae and adults have a neutral reaction. Young nematodes migrating inside the body are attracted to CO2.

“CO2 repulsion in the infective larvae may initiate host-seeking by driving them off of host feces, where CO2 levels are high,” said Navonil Banerjee, a postdoctoral researcher in the Hallem lab and the first author of the study. “And CO2 attraction in worms already inside the body might direct them toward the lungs and intestines, which are high in CO2.”

Hallem, Banerjee and colleagues discovered these reactions by exposing threadworms at different stages of the life cycle to CO2 and studying their behavior. They then identified neurons that detect CO2 and promote associated behavioral responses. They found that these neurons express a receptor called GCY-9, which is known to help nematodes sense CO2. By removing the gene that encodes GCY-9, the threadworms were unable to detect CO2, showing that this gene is necessary for behavioral responses to CO2.

The identification of chemosensory mechanisms that shape the interaction between parasitic nematodes and their human hosts may help scientists design new drugs that target the CO2-sensing pathway. For example, drugs that block GCY-9 function may impair the ability of parasitic worms to navigate within the body by disrupting their ability to detect CO2, which in turn could prevent an infection from establishing or reduce the severity of an existing infection. Future studies will identify additional genes in the CO2-sensing pathway that could act as molecular targets for new antiparasitic drugs.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

END

Skin-penetrating nematodes have a love-hate relationship with carbon dioxide

UCLA neurobiologists’ discovery may lead to new treatments for millions of parasitic infections around the world

2025-01-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Fewer than 1% of U.S. clinical drug trials enroll pregnant participants, study finds

2025-01-21

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — A new study by researchers from the Brown University School of Public Health found that pregnant women are regularly excluded from clinical drug trials that test for safety, raising concerns for the efficacy of these medications for maternal and child health.

The study, published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, analyzed 90,860 drug trials involving women ages 18 to 45 from the past 15 years and found that only 0.8% included pregnant participants. ...

A global majority trusts scientists, wants them to have greater role in policymaking, study finds

2025-01-21

In what is considered the most comprehensive post-pandemic survey of trust in scientists, researchers have found a majority of people around the world carry widespread trust in scientists — believing them to be honest, competent, qualified and concerned with public well-being.

Researchers surveyed more than 72,000 individuals across 68 countries on perceptions of scientists’ trustworthiness, competence, openness and research priorities.

The results, published in the journal Nature Human Behavior, also showed the general public’s desire ...

Transforming China’s food system: Healthy diets lead the way

2025-01-21

According to the study published in Nature Food, China’s current trajectory is misaligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The researchers assessed potential pathways for achieving the SDGs in China by transforming its food system, focusing on dietary changes, climate change mitigation, ecological conservation, and socio-economic development. “Action across all areas of the food system is required to achieve a sustainable food system and efficiently address the wide range of social and environmental ...

Time to boost cancer vaccine work, declare UK researchers

2025-01-21

UK oncology researchers have come together to write the first ever national thought leadership strategy report into cancer vaccine advances and the opportunities these present for those affected by cancer. The strategy report has been published in Cambridge University Press journal Cambridge Prisms: Precision Medicine.

Cancer vaccines hold the potential to revolutionise cancer treatment. These vaccines leverage neoantigens to activate the immune system against tumours, offering a personalised approach to combat cancer. This transformative potential is particularly significant in light of recent advancements in oncology, including ...

Colorado State receives $326M from DOE/EPA to improve oil and gas operations and reduce methane emissions

2025-01-21

The Department of Energy and Environmental Protection Agency have awarded $326 million to three Colorado State University research projects that aim to improve U.S. oil and gas operations and reduce methane emissions nationwide.

The EPA’s Methane Emissions Reduction Program is providing the funding to the CSU Energy Institute and faculty working across multiple departments in the Walter Scott, Jr. College of Engineering, with the goal of helping oil and gas operators improve operational efficiency and manage emissions. The efforts will also support activity to build an inventory of methane emissions, ...

Research assesses how infertility treatments can affect family and work relationships

2025-01-21

Infertility is a problem that affects between 8% and 12% of couples of reproductive age worldwide – for some of them, the problem interrupts a life project, which is the desire to have children and build a family. Advances in technology and medicine have made assisted reproductive treatments possible, but they can be physically and psychologically draining for the couples involved, especially because of expectations of results that may not be achieved.

The emotional impact of treatment is well documented in the scientific literature. ...

New findings shed light on cell health: Key insights into the recycling process inside cells

2025-01-21

A recent study from Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, India has revealed new details about how our cells clean up and recycle waste. This process, known as autophagy, is like a self-cleaning mechanism for cells, helping the cells stay healthy by getting rid of damaged parts and recycling useful components. The process involves formation of a vesicle called autophagosome, which encapsulates the cellular waste. The autophagosome then fuses with another type of vesicle called lysosome. ...

Human papillomavirus infection kinetics revealed in new longitudinal study

2025-01-21

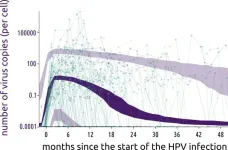

Non-persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) infections are characterized by a sharp increase in viral load followed by a long plateau, according to a study published January 21st in the open-access journal PLOS Biology by Samuel Alizon of the National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), France, and colleagues.

Chronic HPV infection is responsible for more than 600,000 new cancers each year, including nearly all cervical cancers. Infection among young women is common, impacting nearly 20% of women 25 years of age. Fortunately, the vast majority of these infections ...

Antibiotics modulate E. coli’s resistance to phages

2025-01-21

In your coverage, please use this URL to provide access to the freely available paper in PLOS Biology: http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3002952

Article title: Chloramphenicol and gentamicin reduce the evolution of resistance to phage ΦX174 by suppressing a subset of E. coli LPS mutants

Author countries: Germany

Funding: This work was generously supported by funds from the Max Planck Society (L.P.-F.B.). L.P. was supported by the International Max Planck Research ...

Building sentence structure may be language-specific

2025-01-21

Do speakers of different languages build sentence structure in the same way? In a neuroimaging study published in PLOS Biology, scientists from the Max Planck institute for Psycholinguistics, Donders Institute and Radboud University in Nijmegen recorded the brain activity of participants listening to Dutch stories. In contrast to English, sentence processing in Dutch was based on a strategy for predicting what comes next rather than a ‘wait-and-see’ approach, showing that strategies may differ across languages.

While listening to spoken language, people need to link ‘abstract’ knowledge of grammar to ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

Hope for global banana farming in genetic discovery

Mirror image pheromones help beetles swipe right

Prenatal lead exposure related to worse cognitive function in adults

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

Joint and independent associations of gestational diabetes and depression with childhood obesity

Spirituality and harmful or hazardous alcohol and other drug use

New plastic material could solve energy storage challenge, researchers report

Mapping protein production in brain cells yields new insights for brain disease

Exposing a hidden anchor for HIV replication

[Press-News.org] Skin-penetrating nematodes have a love-hate relationship with carbon dioxideUCLA neurobiologists’ discovery may lead to new treatments for millions of parasitic infections around the world