(Press-News.org) It’s difficult to know what birds ‘think’ when they fly, but scientists in Australia and Canada are getting some remarkable new insights by looking inside birds' heads.

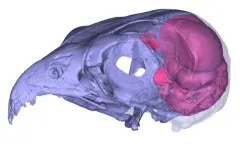

Evolutional biologists at Flinders University in South Australia and neuroscience researchers at the University of Lethbridge in Canada have teamed up to explore a new approach to recreating the brain structure of extinct and living birds by making digital ‘endocasts’ from the area inside a bird skeleton’s empty cranial space.

Published today in Biology Letters, the study led by the ‘Bones and Diversity Lab’ at Flinders and the Iwaniuk Lab at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta has found that dry museum skulls of long-dead birds can provide surprisingly detailed information on a species’ brain, including the size of the birds’ main computation centres for smartness and nimbleness.

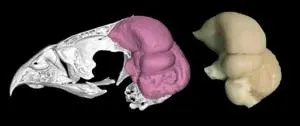

The discovery was made possible by comparing historical microscopic sections of the brain with digital imprints of the bird’s inside braincase, in the largest such study of its kind covering 136 species.

“This showed that the two correspond so closely that there is no need for the actual brain to estimate a bird’s brain proportions,” says the lead author, Flinders University PhD Aubrey Keirnan.

“While ‘bird brain’ is often used as an insult, the brains of birds are so large that they are practically a braincase with a beak. We decided to test if this also means that the brain’s imprint on the skull reflects the proportions of two crucial parts of the actual brain.”

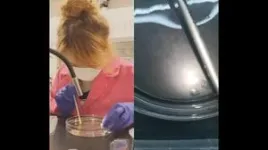

Joined by researchers at the Department of Neuroscience at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta, Canada, the team scanned the skulls of 136 bird species for which they also had microscopic brain sections or literature data.

This allowed them to determine if the volume of two crucial brain parts, the forebrain and the cerebellum, corresponds with the surface areas of the endocasts.

The extremely tight match between the ‘real’ and the ‘digital’ brain volumes surprised the researchers.

“We used computed microtomography to scan the bird skulls. This allows us to digitally fill the brain cavity to get the brain’s imprint, also called an ‘endocast’,” says senior co-author Associate Professor Vera Weisbecker, from Flinders University’s College of Science and Engineering.

“The correlations are nearly 1:1, which we did not expect. But this is excellent news because it allows us to gather insight into the neuroanatomy of elusive, rare and even extinct species without ever even seeing their brains.”

Associate Professor Vera Weisbecker says that advanced digital technologies are providing ever-improving access to some of the oldest puzzles in animal diversity.

“The great thing about digital endocasts is that they are non-destructive. In the old days, people needed to pour liquid latex into a brain case, wait for it to set, and then break the skull to get the endocast.

“Using non-destructive scanning not only allows us to create endocasts from the rarest of birds, it also produces digital files of the skulls and endocasts that can be shared with scientists and the public.”

With an extensive background in bird brain research, University of Lethbridge Professor Andrew Iwaniuk, who co-led this study with Associate Professor Weisbecker, says he did not expect such a clear correlation between brain tissue and endocasts.

“While most of the telencephalon (outer part of the forebrain) is visible from the outer surface, a substantial portion of the cerebellum is obscured by this region. Additionally, the avian cerebellum has ‘folds’ which are often obstructed by a large blood vessel called the occipital sinus,” says Professor Iwaniuk.

“Given that the degree of obscurity can vary between species, I did not expect a strong correlation between endocast surface area and brain volume across all species.”

Professor Iwaniuk adds that the study provides support for existing research by other scientists – including for critically endangered modern birds or perhaps even species gone extinct.

However, the team says that it remains to be seen how well the data can be applied to dinosaurs, which are the birds’ closest extinct relatives.

“For example, crocodiles are the closest living relatives of birds, but their brains look nothing like that of a bird - and their brains do not fill the braincase enough to be as informative,” adds Ms Keirnan.

The article, Avian telencephalon and cerebellum volumes can be accurately estimated from digital brain endocasts (2025) by Aubrey R Keirnan, Felipe Cunha, Sara Citron, Gavin Prideaux, Andrew N Iwaniuk and Vera Weisbecker will be published in Biology Letters (a Royal Society journal) DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.2024.0596

https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2024.0596

Photos: courtesy Aubrey Keirnan Press Release - Keirnan et al. 2025 - Dropbox

END

Empty headed? Largest study of its kind proves ‘bird brain’ is a misnomer

2025-01-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Wild baboons not capable of visual self-awareness when viewing their own reflection

2025-01-22

Published today in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, the study found that while the baboons noticed and responded to a laser mark shone on their arms, legs and hands, they did not react when they saw, via their mirror reflection, the laser on their faces and ears.

It was the first time a controlled laser mark test has been done on these animals in a wild setting and strengthens the evidence from other studies that monkeys don’t recognise their own reflection.

The researchers observed 120 Chacma ...

$14 million supports work to diversify human genome research

2025-01-21

Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has received two large grants renewing funding for the Human Pangenome Reference Sequencing Project. This ambitious program began in 2019 with the goal of increasing the diversity of human genome sequences that are pooled into the widely used reference genome. A thorough representation of human genetic diversity can help researchers discover how genetic variation contributes to disease and perhaps offer new routes to innovative treatments.

Funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute ...

New study uncovers key mechanism behind learning and memory

2025-01-21

AURORA, Colo. (Jan. 22, 2025) – A breakthrough study published today in the Journal of Neuroscience sheds new light on how brain cells relay critical information from their extremities to their nucleus, leading to the activation of genes essential for learning and memory.

Researchers have identified a key pathway that links how neurons send signals to each other, or synaptic activity, to the expression of genes necessary for long-term changes in the brain, providing crucial insights into the molecular processes underlying memory formation.

“These findings illuminate ...

Seeing the unseen: New method reveals ’hyperaccessible’ window in freshly replicated DNA

2025-01-21

San Francisco—January 21, 2025—DNA replication is happening continuously throughout the body, as many as trillions of times per day. Whenever a cell divides—whether to repair damaged tissue, replace old cells, or simply to help the body grow—DNA is copied to ensure the new cells carry the same genetic instructions.

But this fundamental aspect of human biology has been poorly understood, chiefly because scientists lack the ability to closely observe the intricate process of replication. Attempts to do so have relied on chemicals that damage the DNA structure or strategies ...

Extreme climate pushed thousands of lakes in West Greenland ‘across a tipping point,’ study finds

2025-01-21

West Greenland is home to tens of thousands of blue lakes that provide residents drinking water and sequester carbon from the atmosphere. Yet after two months of record heat and precipitation in fall 2022, an estimated 7,500 lakes turned brown, began emitting carbon and decreased in water quality, according to a new study.

Led by Fulbright Distinguished Arctic Scholar and University of Maine Climate Change Institute Associate Director Jasmine Saros, a team of researchers found that the combination of extreme climate events in fall 2022 caused ecological change that ...

Illuminating an asymmetric gap in a topological antiferromagnet

2025-01-21

Topological insulators (TIs) are among the hottest topics in condensed matter physics today. They’re a bit strange: their surfaces conduct electricity, yet their interiors do not, instead acting as insulators. Physicists consider TIs the materials of the future because they host fascinating new quantum phases of matter and have promising technological applications in electronics and quantum computing. Scientists are just now beginning to uncover connections between TIs and magnetism that could unlock new uses for these exotic materials.

A ...

Global public health collaboration benefits Americans, SHEA urges continued support of the World Health Organization

2025-01-21

The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) wants to emphasize the importance of global partnerships in addressing health threats that impact all of us, as Americans and global citizens. We urge President Trump to reconsider the decision to terminate the U.S. relationship with the World Health Organization (WHO). The most effective way to address emerging health threats is through collaborative efforts with international partners. Eliminating U.S. involvement in the WHO would leave our country—and the world—more vulnerable to infectious diseases and less prepared to manage pandemics, fight emerging health threats, ...

Astronomers thought they understood fast radio bursts. A recent one calls that into question.

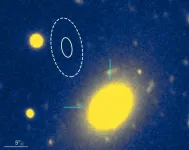

2025-01-21

Astronomer Calvin Leung was excited last summer to crunch data from a newly commissioned radio telescope to precisely pinpoint the origin of repeated bursts of intense radio waves — so-called fast radio bursts (FRBs) — emanating from somewhere in the northern constellation Ursa Minor.

Leung, a Miller Postdoctoral Fellowship recipient at the University of California, Berkeley, hopes eventually to understand the origins of these mysterious bursts and use them as probes to trace the large-scale structure of the universe, a key to its origin and evolution. He had written most of the computer code that allowed ...

AAAS announces addition of Journal of EMDR Practice and Research to Science Partner Journal program

2025-01-21

Journal of EMDR Practice and Research (JEMDR), launched in 2007, is devoted to integrative, state-of-the-art papers about EMDR therapy. It is a broadly conceived interdisciplinary journal that stimulates and communicates research and theory about EMDR therapy and its application to clinical practice. The journal publishes articles on all aspects of EMDR therapy and Adaptive Information Processing (AIP) theory. JEMDR is co-lead by Jenny Ann Rydberg, MA, PhdD cand. (University of Lorraine, Nancy, France) and Derek Farrell, PhD, MBE (Northumbria, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK).

As a member of the Science Partner Journal program, JEMDR will publish on a continuous basis under ...

Study of deadly dog cancer reveals new clues for improved treatment

2025-01-21

Researchers at the University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine and the UF Health Cancer Center have identified a crucial link between a gene mutation and immune system signaling in canine hemangiosarcoma, a discovery that could lead to better treatments for both dogs and humans with similar cancers.

The research focuses on hemangiosarcoma, an aggressive cancer that forms malignant blood vessels in dogs. This life-threatening condition is difficult to diagnose early, as tumors can grow silently before rupturing without warning, leading to emergencies. ...