(Press-News.org)

Fukuoka, Japan - Kyushu University researchers have uncovered a surprising layer of complexity in aldosterone-producing adenomas (APAs)—adrenal gland tumors that drive high blood pressure. Using cutting-edge analysis techniques, they discovered that these tumors harbor at least four distinct cell types, including ones that produce cortisol, the body’s main stress hormone. Published in the week beginning 24 February in PNAS, their findings not only explain why some patients with APAs develop unexpected health issues, like weakened bones, but also pave the way toward new treatment strategies.

“Currently, the only way to cure APAs is through surgery to remove the tumor, and this hasn’t changed for decades,” says first author of the study, Assistant Professor Maki Yokomoto-Umakoshi, from the Department of Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases at Kyushu University Hospital. “To develop new treatment models, such as drug treatments, we urgently need to understand how these tumors work at the molecular level, and how the different cell types interact with each other.”

APAs are benign (non-cancerous) tumors that develop on the adrenal glands—small glands on top of the kidneys that produce important hormones, such as aldosterone, cortisol and sex hormones. Due to their location, APAs are a major cause of primary aldosteronism, a condition in which excessive production of the hormone aldosterone leads to high blood pressure. Primary aldosteronism is responsible for about 5–10% of high blood pressure cases, and patients with APAs have a higher risk of heart and blood vessel problems compared to people with common high blood pressure.

“Without proper treatment, patients can develop serious health problems like heart disease, diabetes, and bone weakness,” adds Yokomoto-Umakoshi.

In this study, the researchers focused on APAs caused by changes in a gene called KCNJ5. This mutation, which accounts for around 40-70% of all cases of these tumors, is typically associated with larger tumors that form at a younger age, as well as more severe symptoms that cannot simply be explained by overproduction of aldosterone. However, the cellular makeup of KCNJ5 tumors, as well as which other hormones the tumors might secrete, has previously proven difficult to study.

To gain a deeper understanding of APAs, the research team, led by Professor Yoshihiro Ogawa from Kyushu University and in collaboration with Osaka University, Kyoto University, and the University of Tokyo, applied a combination of advanced techniques, providing the first comprehensive view of APAs in unprecedented detail. The researchers were able to map where different cell types were located within these tumors, and how they work together. Furthermore, the techniques allowed the researchers to reveal diverse genetic variation within different regions of APAs and identify exactly which hormones the tumors were producing.

The study revealed that APAs are more complex than previously thought, consisting of at least four distinct cell types. The tumor starts with cells that respond to stress, which can then develop into either cells that make aldosterone, or cells that make cortisol. The cortisol-producing cells can then further develop into stromal-like cells that help the tumor to grow.

The researchers also discovered that special immune cells called lipid-associated macrophages were more abundant within the tumor, with a potential role in influencing hormone production and tumor growth.

“Overall, these tumors contain diverse hormone-producing cells that can affect patient’s health in different ways—not just through high blood pressure, but also through other symptoms caused by excess cortisol, like bone weakness,” explains Yokomoto-Umakoshi.

In the future, the researchers plan to use these techniques to extend their analysis to other types of APAs, as well as to other tumors that produce excess hormones. They also hope that their current findings help set the stage for developing future drug treatments for APAs.

“Now we understand more about APAs, it opens up promising new treatment strategies, such as directly targeting lipid-associated macrophages or excess cortisol,” concludes Yokomoto-Umakoshi.

###

For more information about this research, see “Multiomics analysis unveils the cellular ecosystem with clinical relevance in aldosterone-producing adenomas with KCNJ5 mutations” Maki Yokomoto-Umakoshi, Masamichi Fujita, Hironobu Umakoshi, Tatsuki Ogasawara, Norifusa Iwahashi, Kohta Nakatani, Hiroki Kaneko, Tazuru Fukumoto, Hiroshi Nakao, Shojiro Haji, Namiko Kawamura, Shuichi Shimma, Masahide Seki, Yutaka Suzuki, Yoshihiro Izumi, Yoshinao Oda, Masatoshi Eto, Seishi Ogawa, Takeshi Bamba, Yoshihiro Ogawa, PNAS, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2421489122

About Kyushu University

Founded in 1911, Kyushu University is one of Japan's leading research-oriented institutes of higher education, consistently ranking as one of the top ten Japanese universities in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings and the QS World Rankings. The university is one of the seven national universities in Japan, located in Fukuoka, on the island of Kyushu—the most southwestern of Japan’s four main islands with a population and land size slightly larger than Belgium. Kyushu U’s multiple campuses—home to around 19,000 students and 8000 faculty and staff—are located around Fukuoka City, a coastal metropolis that is frequently ranked among the world's most livable cities and historically known as Japan's gateway to Asia. Through its VISION 2030, Kyushu U will “drive social change with integrative knowledge.” By fusing the spectrum of knowledge, from the humanities and arts to engineering and medical sciences, Kyushu U will strengthen its research in the key areas of decarbonization, medicine and health, and environment and food, to tackle society’s most pressing issues.

END

The Huns suddenly appeared in Europe in the 370s, establishing one of the most influential although short-lived empires in Europe. Scholars have long debated whether the Huns were descended from the Xiongnu. In fact, the Xiongnu Empire dissolved around 100 CE, leaving a 300-year gap before the Huns appeared in Europe. Can DNA lineages that bridge these three centuries be found?

To address this question, researchers analyzed the DNA of 370 individuals that lived in historical periods spanning around 800 years, from 2nd century BCE to 6th century CE, encompassing sites in the Mongolian steppe, Central Asia, and the Carpathian Basin of Central Europe. ...

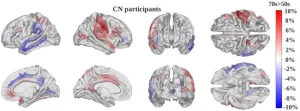

A new artificial intelligence model measures how fast a patient’s brain is aging and could be a powerful new tool for understanding, preventing and treating cognitive decline and dementia, according to USC researchers.

The first-of-its-kind tool can non-invasively track the pace of brain changes by analyzing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Faster brain aging closely correlates with a higher risk of cognitive impairment, said Andrei Irimia, associate professor of gerontology, biomedical engineering, quantitative ...

Starting today, people with Parkinson’s disease will have a new treatment option, thanks to U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of groundbreaking new technology.

The therapy, known as adaptive deep brain stimulation, or aDBS, uses an implanted device that continuously monitors the brain for signs that Parkinson’s symptoms are developing. When it detects specific patterns of brain activity, it delivers precisely calibrated electric pulses to keep symptoms at bay.

The FDA approval covers two treatment algorithms that run on a device made by Medtronic, a medical device company. Both work by monitoring the same part of the brain, called the subthalamic nucleus. ...

Elephants, giraffes, pythons and other large species have higher cancer rates than smaller ones like mice, bats, and frogs, a new study has shown, overturning a 45-year-old belief about cancer in the animal kingdom.

The research, conducted by researchers from the University of Reading, University College London and The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, examined cancer data from 263 species across four major animal groups - amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles. The findings challenge "Peto's paradox," a longstanding idea based on observations from 1977 that suggested ...

LA JOLLA, CA—Children who experience multiple cases of dengue virus develop an army of dengue-fighting T cells, according to a new study led by scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI).

The findings, published recently in JCI Insights, suggest that these T cells are key to dengue virus immunity. In fact, most children who experienced two or more dengue infections showed very minor symptoms—or no symptoms at all—when they caught the virus again.

"We saw a significant T cell response in children who had been infected more than once before," says study leader and LJI Assistant Professor Daniela Weiskopf, Ph.D.

Dengue virus infects up ...

Smart artificial microswimmers—small robots that resemble microorganisms like bacteria or human sperm—could potentially be used for targeted drug delivery, minimally invasive surgery, and even in fertility treatments.

These types of complicated tasks won’t be accomplished by a single microswimmer. Multiple swimmers will be necessary; however, it’s unclear how such groups will move within the chemically and mechanically complex environment of the body’s fluids.

“We know that whenever a swimmer has a neighbor, it swims differently,” says Ebru Demir, an assistant ...

(Charlottesville, VA, Feb. 24, 2025) –

The Center for Open Science (COS) is pleased to announce the appointment of Daniel Correa, Chief Executive Officer of the Federation of American Scientists, and Amanda Montoya, Associate Professor of Quantitative Psychology at UCLA, to the COS Board of Directors. Both will serve three-year terms from 2025 to 2027, bringing valuable expertise in science policy, innovation, research methodology, and open science advocacy.

Daniel Correa is the Chief Executive Officer of the Federation of American Scientists, ...

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

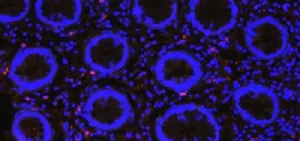

Researchers say they found that infection with a common virus that can be transmitted from mother to fetus before birth significantly worsens an often-fatal complication of premature birth called necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in experiments with mice.

The research team, led by Johns Hopkins Children’s Center investigators and funded by the National Institutes of Health, says the new findings advance the search for better treatments for NEC — a relatively rare condition, but still the most common emergency intestinal complication in preemies.

A report on the study published Feb. 13 in Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology ...

Irvine, Calif., Feb. 24, 2025 — There’s an arms race in medicine – scientists design drugs to treat lethal bacterial infections, but bacteria can evolve defenses to those drugs, sending the researchers back to square one. In the Journal of the American Chemical Society, a University of California, Irvine-led team describes the development of a drug candidate that can stop bacteria before they have a chance to cause harm.

“The issue with antibiotics is this crisis of antibiotic ...

Ketamine can effectively treat depression, but whether depressed patients with alcohol use disorder can safely use ketamine repeatedly remains unclear clinically. To investigate this possibility, Mohamed Kabbaj and colleagues from Florida State University modeled aspects of human depression in rats using long-term isolation and assessed how isolation and alcohol exposure alter ketamine intake. The authors found that a history of isolation and alcohol use influence the rewarding properties of ketamine in a sex-dependent manner.

Female rats took ketamine more than males in general. Prior alcohol use increased female rat ketamine ...