(Press-News.org) A groundbreaking study published in Science Advances sheds new light on the mysterious origins of free-floating planetary-mass objects (PMOs)—celestial bodies with masses between stars and planets.

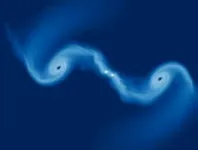

Led by Dr. DENG Hongping of the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, an international team of astronomers used advanced simulations to uncover a novel formation process for these enigmatic objects. The research suggests that PMOs can form directly through violent interactions between circumstellar disks in young star clusters.

The Mystery of Rogue Planetary-Mass Objects

PMOs are cosmic nomads, drifting freely through space, unbound to any star. The mass of these objects is less than 13 times that of Jupiter. They are often observed in young star clusters like the Trapezium Cluster in Orion. While their existence is well-documented, their origin has long puzzled scientists. Previous theories proposed that PMOs could be failed stars or planets ejected from their solar systems. However, these models fail to explain the large number of PMOs, their frequent binary pairings, and their synchronized motion with stars within clusters.

"PMOs don't fit neatly into existing categories of stars or planets," said Dr. DENG, corresponding author of the study. "Our simulations show they likely form through a completely different process—one tied to the chaotic dynamics of young star clusters."

A Cosmic Tug-of-War: How Disks Collide to Create PMOs

Using high-resolution hydrodynamic simulations, the researchers recreated close encounters between two circumstellar disks—rotating annuli of gas and dust surrounding young stars. When these disks collide at speeds of 2–3 km/s and distances of 300–400 astronomical units (AU), their gravitational interactions stretch and compress gas into elongated "tidal bridges."

These tidal bridges eventually collapse into dense filaments, which further fragment into compact cores. When these filaments reach a critical mass, they produce PMOs with masses of about ten times that of Jupiter. The simulations also revealed that up to 14% of PMOs form in pairs or triplets, with 7–15 AU separations, explaining the high rate of PMO binaries in some clusters. Frequent disk encounters in dense environments like the Trapezium Cluster could generate hundreds of PMOs, explaining the observed overabundance.

Why PMOs Are Unique

PMOs are distinct in their formation. Unlike ejected planets, they move in sync with the stars in their host clusters and inherit material from the outer regions of circumstellar disks. This results in a unique composition, with PMOs reflecting the metal-poor outskirts of these disks, where heavy elements are scarce. Many PMOs also retain gas disks up to 200 AU in diameter, suggesting the potential for lunar or even planetary formation around these rogue objects.

"This discovery partly reshapes how we view cosmic diversity," said co-author Prof. Lucio Mayer from the University of Zurich, "PMOs may represent a third class of objects, born not from the raw material of star-forming clouds or via planet-building processes, but rather from the gravitational chaos of disk collisions."

Looking Ahead

The team, including researchers from the University of Hong Kong, the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory, the University of California Santa Cruz, and the University of Zurich, plan further studies to explore the chemical makeup and disk structures of PMOs. Upcoming research on PMOs in various clusters will consolidate the theory of their formation and population properties.

END

New study reveals how rogue planetary-mass objects form in young star clusters

2025-02-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

School of rock: Properties of rocks in fault zones contribute to earthquake generation

2025-02-26

ANN ARBOR—Earthquakes occur along fault lines between continental plates, where one plate is diving beneath another. Pressure builds between each plate, called fault stress. When this stress builds enough to release, the plates slip and grind against each other, causing an earthquake.

Researchers have long thought that this force is the central driver of earthquakes. But another force is also in the mix: the properties of the rocks in the fault zones along the plate interface. This includes both the structure of the rock as well as how the rocks are arranged along the zones.

Now, a University of Michigan study looking at a small ...

Aston University microbiologist calls for public vigilance and urgent action on the danger of raw sewage in UK seas

2025-02-26

Dr Jonathan Cox writes in Microbiology about the pathogens in raw sewage and the “significant” danger to public health when it ends up in the sea

He contracted a lung infection in 2024, likely from exposure to raw sewage in the sea where he had been swimming

He urges people to check for sewage reports before heading to the beach and calls for investment to improve infrastructure.

Aston University microbiologist Dr Jonathan Cox has written an article for the journal Microbiology on ...

Supercomputing illuminates detailed nuclear structure

2025-02-26

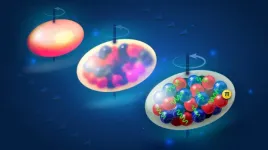

Using the Frontier supercomputer at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory, researchers have developed a new technique that predicts nuclear properties in record detail.

The study revealed how the structure of a nucleus relates to the force that holds it together. This understanding could advance efforts in quantum physics and across a variety of sectors, from to energy production to national security.

“Our reliable predictions will bring new insights to the study of nuclear forces and structure,” said Zhonghao Sun of Louisiana State University, formerly of ORNL.

The team’s findings, published in the ...

Ohio tests new model for providing mental health resources to youth in rural communities

2025-02-26

During and after the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth appointments became a more common part of the American health care system. But even as telehealth options grow, barriers such as long waitlists or a lack of a stable internet connection mean many communities still do not have access to care, particularly for mental health services.

The University of Cincinnati, the Adams County Health Department (ACHD) and other local partners are testing a new collaborative care model that aims to remove these barriers and provide more students access to telemental health care. The team recently received a $1.75 million grant from the Health ...

Breast-conserving surgery improves sexual well-being compared to breast reconstruction

2025-02-26

February 26, 2025 — For women with breast cancer, breast-conserving therapy (BCT) is associated with improved sexual well-being, compared to mastectomy followed by breast reconstruction, reports a study in the March issue of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery®, the official medical journal of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

"In our study, patients undergoing BCT scored consistently higher on a measure of sexual well-being, compared to total mastectomy and breast reconstruction," comments Jonas A. Nelson, MD, MPH, of Memorial ...

What can theoretical physics teach us about knitting?

2025-02-26

The practice of purposely looping thread to create intricate knit garments and blankets has existed for millennia. Though its precise origins have been lost to history, artifacts like a pair of wool socks from ancient Egypt suggest it dates back as early as the 3rd to 5th century CE. Yet, for all its long-standing ubiquity, the physics behind knitting remains surprisingly elusive.

“Knitting is one of those weird, seemingly simple but deceptively complex things we take for granted,” says ...

Discovery of rare gene variants provides window into tailored type 2 diabetes treatment

2025-02-26

OKLAHOMA CITY – A new study published in Communications Medicine, a Nature publication, details the discovery of rare gene variants that increase the prevalence of Type 2 diabetes in multiple generations of Asian Indian people. The unusual finding is a step toward more targeted treatment for all people with Type 2 diabetes, a disease with complex genetic influences.

“We wanted to study several generations of Asian Indians because understanding genetics in families can give us better information, and Asian Indians have up to six times higher risk of developing Type 2 diabetes than Europeans. In addition, Asian Indians tend to live clustered together and marry ...

UMCG perfusion technique for donor livers gets worldwide followings

2025-02-26

The perfusion technique developed at UMCG to test the quality of donor livers led to a record number of liver transplants last year. Not only in Groningen, but throughout the Netherlands. Meanwhile, there is worldwide interest in this perfusion technique.

Donor livers can only be stored outside the body for a short time, up to 6 to 10 hours. The organ must therefore get to the recipient as quickly as possible. As a result, transplants have always been under great time pressure. The UMCG has had an ‘Organ Preservation & ...

New method developed to dramatically enhance bioelectronic sensors

2025-02-26

In a breakthrough that could transform bioelectronic sensing, an interdisciplinary team of researchers at Rice University has developed a new method to dramatically enhance the sensitivity of enzymatic and microbial fuel cells using organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs). The research was recently published in the journal Device.

The innovative approach amplifies electrical signals by three orders of magnitude and improves signal-to-noise ratios, potentially enabling the next generation of highly sensitive, low-power biosensors for health and environmental monitoring.

“We have demonstrated a simple yet powerful technique to amplify weak bioelectronic signals ...

Researchers identify potential link between retinal changes, Alzheimer’s disease

2025-02-26

INDIANAPOLIS- A team of scientists at the Indiana University School of Medicine has identified that an eye condition affecting the retina, the light-sensing tissue in the back of the eye, may serve as an early indicator for Alzheimer's disease. Their findings, published in Alzheimer's & Dementia, offer new insights into the potential use of retinal changes as early biomarkers for Alzheimer's, which could improve diagnosis and treatment of neurodegenerative disease.

The research was led by IU School of Medicine PhD Student Surabhi D. Abhyankar, MS, alongside colleagues from the school's departments of ophthalmology and biochemistry and molecular biology, the ...