(Press-News.org) ITHACA, N.Y. -- Transposons, or “jumping genes” – DNA segments that can move from one part of the genome to another – are key to bacterial evolution and the development of antibiotic resistance.

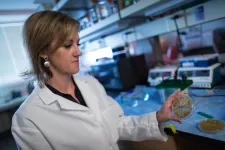

Cornell University researchers have discovered a new mechanism these genes use to survive and propagate in bacteria with linear DNA, with applications in biotechnology and drug development.

In a paper under embargo in Science until 2pm ET on March 6, 2025, researchers show that transposons can target and insert themselves at the ends of linear chromosomes, called telomeres, within their bacterial host. In Streptomyces – historically one of the most significant bacteria for antibiotic development – they found that transposons controlled the telomeres in nearly a third of the chromosomes.

“This is a big part of their biology,” said senior author Joseph Peters, professor of microbiology. “Bacteria are like these little tinkerers. They’re always collecting these mobile DNA pieces, and they’re making new functions all the time – everything in antibiotic resistance is really about mobile genetic elements and almost always transposons that can move between bacteria.”

With some technologies not available even five years ago, the researchers identified several families of transposons in cyanobacteria and Streptomyces that, using different mechanisms, can find and insert themselves at the telomere, with benefits for the transposon and their bacterial host. For one, inserting at the end of the chromosome helps the transposon avoid genes for the cell’s core functioning, which reside in the middle of the chromosomes; transposons that can target the ends are less likely to disrupt an essential function or cause cell death.

“If you could target the end, you’re less likely to knock out something that the host wants, and then these ends, by various systems, are transferred between cells,” Peters said. “For any element to survive – a transposon, bacteria – they really need to be able to do those two things: They need to not cause too much damage, and they need a way to move to new hosts. By inserting into the telomeres, they’re able to do both.”

Transposons have been found clustered at the chromosome ends in eukaryotic cells, but this is the first time it’s been documented in bacteria with linear chromosomes, and the researchers found that bacterial transposons (versus eukaryotes) use unique mechanisms to control the telomeres.

Transposons are usually flanked by protein-binding sequences that indicate where to excise the DNA element and move it to a new location. In Streptomyces, researchers observed that the transposons at the telomeres were one-sided, with a traditional transposon sequence on one end with the other end being the telomere. This functionally allows the transposon to be the telomere, making it essential to the cell generally.

“What it lets them do is become essential to the host, because they now control the telomere, and if the element got deleted along with this system, the host would die,” Peters said.

The researchers found one subfamily of telomere-targeting transposons that coopted a CRISPR system – normally used by bacteria to defend against viruses – to target and insert itself into the chromosome ends. This process is further confirmation of previous research in Peters’ lab that found transposons using CRISPR systems to move around genomes, opening the potential for a new gene-editing tool that would allow for larger sections of DNA to be inserted than the now widely used CRISPR-Cas9.

“The transposons keep grabbing these systems and coopting them in different ways,” Peters said. “In this paper, we explained a new one of these elements using a CRISPR-Cas system to target the telomeres.”

The insights – especially into Streptomyces, which is difficult to manipulate in the lab and accounts for the discovery of many of our antibiotics – could prove useful for drug development, as transposons drive bacterial evolution and may direct researchers to new antibiotics and other useful products encoded on these transposons.

“Most of life on the planet is microbes, and specifically bacteria,” Peters said. “We want to understand how these living organisms function, but then we want to see how we can use these systems for the betterment of humankind.”

Co-authors include postdoctoral researchers Shan-Chi (Popo) Hsieh and Michael T. Petassi; doctoral student Richard Schargel; and partners at the University of Geneva, Orsolya Barabas and Máté Fülöp.

The research was supported with funding from the National Institutes of Health and the European Research Council.

-30-

END

Bacterial ‘jumping genes’ can target and control chromosome ends

2025-03-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists identify genes that make humans and Labradors more likely to become obese

2025-03-06

Researchers studying British Labrador retrievers have identified multiple genes associated with canine obesity and shown that these genes are also associated with obesity in humans.

The dog gene found to be most strongly associated with obesity in Labradors is called DENND1B. Humans also carry the

DENND1B gene, and the researchers found that this gene is also linked with obesity in people.

DENND1B was found to directly affect a brain pathway responsible for regulating the energy balance in the body, called the leptin melanocortin pathway.

An additional four genes associated with canine obesity, ...

Early-life gut microbes may protect against diabetes, research in mice suggests

2025-03-06

The microbiome shapes development of insulin-producing cells in infancy, leading to long-term changes in metabolism and diabetes risk, new research in mice has found.

The results could ultimately help doctors reduce the risk of type 1 diabetes—or potentially even restore lost metabolic function in adulthood—by providing specific gut microbes that help the pancreas grow and heal.

The findings are published in Science.

The critical window

Mice that are exposed to broad-spectrum antibiotics in early life have worse metabolic health in the long term, the researchers found. If the mice received antibiotics during a 10-day window shortly after birth, they developed ...

Study raises the possibility of a country without butterflies

2025-03-06

Butterflies are disappearing in the United States. All kinds of them. With a speed scientists call alarming, and they are sounding an alarm.

A sweeping new study published in Science for the first time tallies butterfly data from more than 76,000 surveys across the continental United States. The results: between 2000 and 2020, total butterfly abundance fell by 22% across the 554 species counted. That means that for every five individual butterflies within the contiguous U.S. in the year 2000, there were only four in 2020.

“Action must be taken,” ...

Study reveals obesity gene in dogs that is relevant to human obesity studies

2025-03-06

Dogs are a compelling model of human obesity, in part because they develop obesity due to similar environmental influences as people. In a genome-wide association study (GWAS) of Labrador retrievers, researchers have identified an obesity-related gene – DENND1B – that may also influence obesity in humans. These findings highlight the value of using non-traditional animal models to study complex diseases and highlight the gene’s potential as a target for future obesity research across species. Obesity is a ...

A rapid decline in US butterfly populations

2025-03-06

Butterfly populations across the United States are in alarming decline, according to a new study, with total abundance falling by 22% in just 20 years. Such widespread and worrisome losses portend broader environmental threats and emphasize the urgent need for conservation action. “Our national-scale findings paint the most complete – and concerning – picture of the status of butterflies across the country in the early 21st century,” write the authors. The decline of biodiversity has been extensively documented worldwide. Among these losses, the decline of insects is particularly ...

Indigenous farming practices have shaped manioc’s genetic diversity for millennia

2025-03-06

A new genomic study reveals how Indigenous traditional farming practices have shaped the evolution of manioc – one of the world’s most important staple crops – for the better. The domestication of plants and the rise of agriculture were transformative events in human history. Today, a few staple crops provide most human calories, including manioc (cassava or yuca), a vital root crop that sustains nearly a billion people across the tropics. Although it ranks as the world’s seventh most significant crop, manioc is primarily cultivated on small farms. The plant’s ...

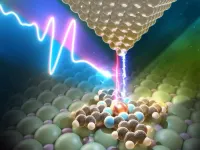

Controlling electrons in molecules at ultrafast timescales

2025-03-06

Scientists at YOKOHAMA National University, in collaboration with RIKEN and other institutions in Japan and Korea, have made an important discovery about how electrons move and behave in molecules. This discovery could potentially lead to advances in electronics, energy transfer, and chemical reactions. Published in the Journal, Science, their study reveals a new way to control the distribution of electrons in molecules using very fast phase-controlled pulses of light in the terahertz range.

Atoms and molecules contain negatively charged electrons that usually stay in specific energy levels, like layers, ...

Tropical forests in the Americas are struggling to keep pace with climate change

2025-03-06

Embargoed until 14:00 US Eastern Time, Thursday 6 March 2025

Tropical forests in the Americas are struggling to keep pace with climate change

Tropical rainforests play a vital role in global climate regulation and biodiversity conservation. However, a major new study published in Science reveals that forests across the Americas are not adapting quickly enough to keep pace with climate change, raising concerns about their long-term resilience.

The research, led by Dr. Jesús Aguirre-Gutiérrez from the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute (ECI), involved over 100 scientists ...

Brain mapping unlocks key Alzheimer’s insights

2025-03-06

Researchers from The University of Texas at Arlington and the University of California–San Francisco have used a new brain-mapping technique to identify memory-related brain cells vulnerable to protein buildup, a key factor in the development of Alzheimer’s disease, an incurable, progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills.

In Texas, nearly half a million people live with Alzheimer’s disease, a form of dementia that costs the state approximately $24 billion in caregiver time, according to the Texas Department of State Health Services. Texas ranks fourth in the nation for Alzheimer’s cases ...

Clinical trial tests novel stem-cell treatment for Parkinson’s disease

2025-03-06

A recently launched Phase 1 clinical trial at Mass General Brigham is examining the safety and feasibility of a groundbreaking treatment approach for Parkinson’s disease in which a patient’s stem cells are reprogrammed to replace dopamine cells in the brain damaged by the disease. The first-of-its-kind trial of an autologous stem cell transplant, based on research and technologies invented and validated preclinically at McLean Hospital’s Neuroregeneration Research Institute (NRI), has enrolled and treated three patients at Brigham and Women’s ...