Sulfate-reducing bacteria break down a large proportion of the organic carbon in oxygen-free zones of the Earth, and in the seabed in particular. Among these important microbes, the Desulfobacteraceae family of bacteria stands out because its members are able to break down a wide variety of compounds – including some that are poorly degradable – to their end product, carbon dioxide (CO2).

A team of researchers led by Dr Lars Wöhlbrand and Prof. Dr Ralf Rabus from the University of Oldenburg, Germany, has investigated the role of these microbes in detail and published the findings of their comprehensive study in the prestigious journal Science Advances.

The team reports that the bacteria are distributed across the globe and possess a complex metabolism that displays modular features: all the studied strains possess the same central metabolic architecture for harvesting energy, for example. However, some strains possess additional strain-specific molecular modules that enable them to utilise diverse organic substances. The researchers attribute this group of bacteria's environmental success to this versatile modular system. They also explain that their study provides new analytical tools to further advance our understanding of the role of sulfate-reducing microbes in the global carbon cycle and their relevance for the climate.

Life at the thermodynamic limit

"These sulfate reducers live their lives at the thermodynamic limit," explains Rabus, who heads the General and Molecular Microbiology working group at the University of Oldenburg's Institute for Chemistry and Biology of the Marine Environment (ICBM). These bacteria use sulfate rather than oxygen for respiration, and they harvest only a fraction of the energy that aerobic bacteria can extract from the degradation of organic substances. Yet they are extremely active and play a key role in the breakdown of organic matter in the seabed. "It is estimated that in coastal waters and shelf areas, where particularly large amounts of organic matter are deposited, sulfate-reducing bacteria account for more than half of the degradation in the seabed," Rabus notes.

He explains that the dominant members of the bacterial community often belong to the Desulfobacteraceae family, and the activity of these microbes is clearly visible in environments such as mudflats, where the sediment only a few millimetres below the surface is oxygen-free. "This results in the formation of foul-smelling hydrogen sulfide and the distinctive black iron sulfide precipitates," he explains.

However, so far little was known about the role members of the Desulfobacteraceae family play in the degradation of organic material at the global level, or about the underlying molecular mechanisms. To obtain a more detailed overview, the team first analysed the global prevalence of these sulfate-reducing bacteria. A study of the relevant literature revealed that they are distributed worldwide and occur in all marine areas between the Arctic and Antarctic – particularly in low-oxygen or oxygen-free environments, as expected.

Similar molecular strategies to break down organic compounds

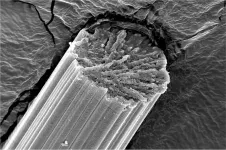

In the next step, the researchers cultivated six very different strains of Desulfobacteraceae. "Some are specialists that only break down certain compounds while others can utilise a broad spectrum of substances. Some are small and spherical, others are elongated or even filamentous," the study's lead author Lars Wöhlbrand explains. In order to decode their metabolism, the researchers fed the microbes a total of 35 different substances (substrates) ranging from simple fermentation products to long-chain fatty acids and poorly degradable aromatic compounds. A total of 80 test conditions were used for the six strains studied. The team then analysed which genes are activated during the degradation of these substances and which proteins the microbes use for this process. It emerged that the different strains employ very similar molecular strategies to break down the substances and all six strains also use the same highly energy-efficient pathway for central metabolism.

The researchers conclude that the Desulfobacteraceae work together like a team, and are consequently able to break down a large pool of different substrates under a variety of geochemical conditions and at a wide range of different geographical locations. "There is no single, dominant key species," Rabus stresses. Instead, the bacteria function as a collaborative community, similar to a football team: "Every team has a goalkeeper and a striker, but each team also does things in its own way," Wöhlbrand adds. This versatility may also explain why the Desulfobacteraceae are among the most widespread sulfate reducers worldwide.

Together with Prof. Dr Michael Schloter from the Technical University of Munich, Germany, the researchers then investigated whether the genetic blueprints for certain key modules in the metabolic network could be detected in sediment samples. And in effect, they discovered the selected genes in almost all the analysed samples taken from marine areas that ranged from shallow waters to the deep sea, including nutrient-rich estuaries, hot and cold deep-sea springs and sediments from the oxygen-poor Black Sea.

The team concludes that its analysis first of all underscores the key role played by Desulfobacteriaceae in carbon breakdown on a global level, and secondly, it demonstrates that the investigated genes can be used as analytical tools to study microbial activity directly in the seabed. "The importance of sulfate reducers in the carbon cycle has probably been underestimated so far," says Prof. Dr Michael Winklhofer from the University of Oldenburg's Institute of Biology and Environmental Sciences, who was involved in the analysis. The geophysicist adds that the role of these anaerobic microbes in carbon degradation processes in coastal areas may increase in the future, because the oxygen content of the oceans has been decreasing since around 1960 as a result of over-fertilisation and global warming.

END