The skin consists of two primary layers. The epidermis, the outermost layer, is predominantly made up of keratinocytes, while the deeper dermis contains blood vessels, nerves, and structural proteins such as collagen, which give the skin its strength and texture. Traditionally, fibroblasts—specialized supporting cells within the dermis—have been believed to play a key role in producing collagen.

In humans, collagen is formed before and after birth. It has been believed that fibroblasts play an exclusive role in collagen production in the skin, and no keratinocytes contribute to collagen production. The statement “Collagen production in the human skin is achieved by fibroblasts” has been an unspoken agreement in the skin research field.

However, in a groundbreaking study published in Volume 16 of Nature Communications on February 24, 2025, scientists from Okayama University, Japan, challenged this long-standing belief. Using the transparent skin of axolotls, an aquatic amphibian widely used in dermatology research, they uncovered a different mechanism for dermal collagen formation.

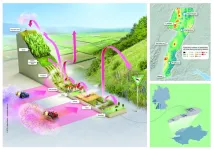

To track collagen development, the researchers examined axolotl skin at different growth stages—5 cm, 8 cm, 10 cm, and 12 cm in length—using advanced fluorescence-based microscopy techniques. At 5 cm, the axolotl’s skin consisted of an epidermis with keratinocytes and a thin, fibroblast-free collagen layer in the dermis, which they named the stratum coniunctum. As the axolotl grew, the collagen layer thickened, and only later did fibroblasts begin migrating into it, eventually forming three distinct dermal layers beneath the epidermis: the stratum baladachinum, stratum spongiosum, and stratum compactum. Each of these layers had a unique collagen structure, none of which matched the original pattern of the stratum coniunctum.

Since collagen was already present before fibroblasts start contributing the dermal collagen formation, the team searched for the source of collagen production by a novel collagen labeling technique that can clarify newly synthesized collagen fibers. The results were surprising: strong fluorescent signals were detected in collagen fibers made by keratinocytes, not fibroblasts. “So far, fibroblasts have been thought to be the major contributors to skin collagen. All efforts in cosmetic science and skin medical research have focused on fibroblast regulation. But the present study demands a change in mindset. We clarified that keratinocytes are primarily responsible for dermal collagen formation,” explains Ayaka Ohashi, a Ph.D. student at the Graduate School of Environmental, Life, Natural Science, and Technology at Okayama University.

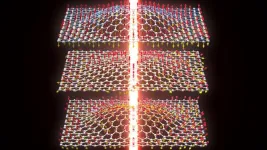

Further investigation revealed that keratinocytes produce collagen in a structured, grid-like arrangement on their undersurface. Later, fibroblasts, which have a lattice-like structure and finger-like projections, migrated into this collagen layer, modifying, and reinforcing it. To confirm that this process is not unique to axolotls, the researchers examined other vertebrate models, including zebrafish, chick embryos, and mammalian (mouse) embryos. Their findings were consistent across all species, suggesting that keratinocyte-driven collagen production is an evolutionarily conserved mechanism.

Understanding how collagen forms before birth is crucial for addressing skin aging and developing new treatments for collagen-related conditions. “Axolotls can maintain good skin texture and appearance for a long time. I mean, they have a sort of eternal youth,” says Professor Akira Satoh from Okayama University. “This might be because they continue producing collagen in keratinocytes for a long time. On the other hand, we humans cannot maintain collagen production in keratinocytes after birth. If we can clarify the mechanism that allows axolotls to keep keratinocytes producing collagen throughout their lifetime, we might be able to achieve eternal youth, just like axolotls.”

This discovery reshapes our understanding of skin biology and could lead to breakthroughs in regenerative medicine, wound healing, and cosmetic formulations. Current skincare products primarily target fibroblast activity, but future treatments may need to focus on stimulating keratinocyte-driven collagen production instead.

By overturning a decades-old belief, this research paves the way for a new era in skincare science—one that could bring us closer to maintaining youthful, resilient skin for a lifetime.

About Okayama University, Japan

As one of the leading universities in Japan, Okayama University aims to create and establish a new paradigm for the sustainable development of the world. Okayama University offers a wide range of academic fields, which become the basis of the integrated graduate schools. This not only allows us to conduct the most advanced and up-to-date research, but also provides an enriching educational experience.

Website: https://www.okayama-u.ac.jp/index_e.html

About Professor Akira Satoh from Okayama University, Japan

Dr. Akira Satoh is a faculty of the Graduate School of Environmental, Life, Natural Science, and Technology at Okayama University, Japan. He has a total of 68 publications to his name, with his primary focus being Life Sciences and Developmental Biology. He works on amphibian limb models to understand why humans have lost their ability to regenerate organs. He was conferred ‘The Young Scientists’ Prize – 2015’ by the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan.

About Ayaka Ohashi from Okayama University, Japan

Ayaka Ohashi is a Ph.D. student at the Graduate School of Environmental, Life, Natural Science, and Technology at Okayama University, Japan. She works with amphibian animal models, primarily axolotl to gain deeper insights into various aspects of developmental biology, with 9 publications to her credit. Her recent works were focused on skin, muscle, and limb regeneration.

END