(Press-News.org) Though we learn so much during our first years of life, we can’t, as adults, remember specific events from that time. Researchers have long believed we don’t hold onto these experiences because the part of the brain responsible for saving memories — the hippocampus — is still developing well into adolescence and just can’t encode memories in our earliest years. But new Yale research finds evidence that’s not the case.

In a study, Yale researchers showed infants new images and later tested whether they remembered them. When an infant’s hippocampus was more active upon seeing an image the first time, they were more likely to appear to recognize that image later.

The findings, published March 20 in Science, indicate that memories can indeed be encoded in our brains in our first years of life. And the researchers are now looking into what happens to those memories over time.

Our inability to remember specific events from the first few years of life is called “infantile amnesia.” But studying this phenomenon is challenging.

“The hallmark of these types of memories, which we call episodic memories, is that you can describe them to others, but that’s off the table when you’re dealing with pre-verbal infants,” said Nick Turk-Browne, professor of psychology in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, director of Yale’s Wu Tsai Institute, and senior author of the study.

For the study, the researchers wanted to identify a robust way to test infants’ episodic memories. The team, led by Tristan Yates, a graduate student at the time and now a postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University, used an approach in which they showed infants aged four months to two years an image of a new face, object, or scene. Later, after the infants had seen several other images, the researchers showed them a previously seen image next to a new one.

“When babies have seen something just once before, we expect them to look at it more when they see it again,” said Turk-Browne. “So in this task, if an infant stares at the previously seen image more than the new one next to it, that can be interpreted as the baby recognizing it as familiar.”

In the new study, the research team, which over the past decade has pioneered methods for conducting functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) with awake infants (which has historically been difficult because of infants’ short attention spans and inability to stay still or follow directions), measured activity in the infants’ hippocampus while they viewed the images.

Specifically, the researchers assessed whether hippocampal activity was related to the strength of an infant’s memories. They found that the greater the activity in the hippocampus when an infant was looking at a new image, the longer the infant looked at it when it reappeared later. And the posterior part of the hippocampus (the portion closer to the back of the head) where encoding activity was strongest is the same area that’s most associated with episodic memory in adults.

These findings were true across the whole sample of 26 infants, but they were strongest among those older than 12 months (half of the sample group). This age effect is leading to a more complete theory of how the hippocampus develops to support learning and memory, said Turk-Browne.

Previously, the research team found that the hippocampus of infants as young as three months old displayed a different type of memory called “statistical learning.” While episodic memory deals with specific events, like, say, sharing a Thai meal with out-of-town visitors last night, statistical learning is about extracting patterns across events, such as what restaurants look like, in which neighborhoods certain cuisines are found, or the typical cadence of being seated and served.

These two types of memories use different neuronal pathways in the hippocampus. And in past animal studies, researchers have shown that the statistical learning pathway, which is found in the more anterior part of the hippocampus (the area closer to the front of the head), develops earlier than that of episodic memory. Therefore, Turk-Browne suspected that episodic memory may appear later in infancy, around one year or older. He argues that this developmental progression makes sense when thinking about the needs of infants.

“Statistical learning is about extracting the structure in the world around us,” he said. “This is critical for the development of language, vision, concepts, and more. So it’s understandable why statistical learning may come into play earlier than episodic memory.”

Even still, the research team’s latest study shows that episodic memories can be encoded by the hippocampus earlier than previously thought, long before the earliest memories we can report as adults. So, what happens to these memories?

There are a few possibilities, says Turk-Browne. One is that the memories may not be converted into long-term storage and thus simply don’t last long. Another is that the memories are still there long after encoding and we just can’t access them. And Turk-Browne suspects it may be the latter.

In ongoing work, Turk-Browne’s team is testing whether infants, toddlers, and children can remember home videos taken from their perspective as (younger) babies, with tentative pilot results showing that these memories might persist until preschool age before fading.

The new findings, led by Yates, provides an important connection.

“Tristan’s work in humans is remarkably compatible with recent animal evidence that infantile amnesia is a retrieval problem,” said Turk-Browne. “We’re working to track the durability of hippocampal memories across childhood and even beginning to entertain the radical, almost sci-fi possibility that they may endure in some form into adulthood, despite being inaccessible.”

END

Why don’t we remember being a baby? New study provides clues

2025-03-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The cell’s powerhouses: Molecular machines enable efficient energy production

2025-03-20

Mitochondria are the powerhouses in our cells, producing the energy for all vital processes. Using cryo-electron tomography, researchers at the University of Basel, Switzerland, have now gained insight into the architecture of mitochondria at unprecedented resolution. They discovered that the proteins responsible for energy generation assemble into large “supercomplexes”, which play a crucial role in providing the cell’s energy.

Most living organisms on our planet-whether plants, animals, or ...

Most of the carbon sequestered on land is stored in soil and water

2025-03-20

Recent studies have shown that carbon stocks in terrestrial ecosystems are increasing, mitigating around 30% of the CO2 emissions linked to human activities. The overall value of carbon sinks on the earth's surface is fairly well known—as it can be deduced from the planet's total carbon balance anthropogenic emissions, the accumulation of carbon in the atmosphere and the ocean sinks—yet, researchers know very little about carbon distribution between the various terrestrial pools: living vegetation—mainly forests—and nonliving carbon pools—soil organic matter, sediments at the bottom of lakes and rivers, wetlands, ...

New US Academic Alliance for the IPCC opens critical nomination access

2025-03-20

WASHINGTON — The American Geophysical Union and the U.S. Academic Alliance for the IPCC today open calls for U.S. researchers to self-nominate as experts, authors and review editors for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Seventh Assessment Report through a new application portal. The IPCC nomination period opened in early March and will close in mid-April.

USAA-IPCC is a newly established network of U.S. academic institutions registered as observers with the IPCC. Both observer organizations and governments may nominate experts for ...

Breakthrough molecular movie reveals DNA’s unzipping mechanism with implications for viral and cancer treatments

2025-03-20

Scientists at the University of Leicester have captured the first detailed “molecular movie” showing DNA being unzipped at the atomic level – revealing how cells begin the crucial process of copying their genetic material.

The groundbreaking discovery, published in the prestigious journal Nature, could have far-reaching implications, helping us to understand how certain viruses and cancers replicate.

Using cutting edge cryo-electron microscopy, the team of scientists were able to visualise a helicase enzyme (nature’s DNA unzipping machine) in the process of unwinding DNA. DNA helicases are essential during DNA replication because ...

New function discovered for protein important in leukemia

2025-03-20

The protein (Exportin-1) is often found in high levels in patients with leukemia, other cancers

Protein was previously known to move materials out of a cell’s nucleus

New findings suggest protein may also stimulate transcription, which if hijacked, could contribute to abnormal cell division (cancer)

Future anti-cancer therapies that target Exportin-1’s role in transcription may be less toxic or more effective than current therapies

EVANSTON, Ill. --- Researchers from Northwestern University have stumbled upon a previously unobserved function of a protein found in the cell nuclei of all flora and fauna. In addition to exporting ...

Tiny component for record-breaking bandwidth

2025-03-20

Plasmonic modulators are tiny components that convert electrical signals into optical signals in order to transport them through optical fibres. A modulator of this kind had never managed to transmit data with a frequency of over a terahertz (over a trillion oscillations per second). Now, researchers from the group led by Jürg Leuthold, Professor of Photonics and Communications at ETH Zurich, have succeeded in doing just that. Previous modulators could only convert frequencies up to 100 or 200 gigahertz ...

In police recruitment efforts, humanizing officers can boost interest

2025-03-20

Many U.S. police departments face a serious recruiting and staffing crisis, which has spurred a re-examination of recruitment methods. In a new study, researchers drew on the field of intergroup communication to analyze how police are portrayed in recruitment materials to determine whether humanizing efforts make a difference. The study found that presenting officers in human terms boosted participants’ interest in policing as a career.

The study was conducted by researchers at the University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB), Texas State University (TXST), ...

Fully AI driven weather prediction system could start revolution in forecasting

2025-03-20

A new AI weather prediction system, Aardvark Weather, can deliver accurate forecasts tens of times faster and using thousands of times less computing power than current AI and physics-based forecasting systems, according to research published today (Thursday 20 March) in Nature.

Aardvark has been developed by researchers from the University of Cambridge supported by the Alan Turing Institute, Microsoft Research and the European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting, providing a blueprint for a completely new approach to weather forecasting with the potential to transform current practices.

The ...

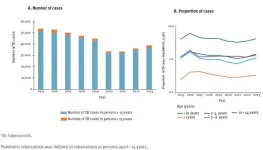

Tuberculosis in children and adolescents: EU/EEA observes a rise in 2023

2025-03-20

As young children have an increased risk of developing tuberculosis (TB) disease during the first year after infection, childhood TB serves as an indicator of ongoing transmission within a community.

In 2023, 1,689 children and young adolescents below the age of 15 years were diagnosed with tuberculosis in the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA) countries. This particular age group usually represents a relatively small proportion among the overall reported TB cases in the region, with a range from 3.4% in 2021 for example to 6.4% in 2016.

However, the data for children and young ...

How family background can help lead to athletic success

2025-03-20

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Americans have long believed that sports are one area in society that offers kids from all backgrounds the chance to succeed to the best of their abilities.

But new research suggests that this belief is largely a myth, and that success in high school and college athletics often is influenced by race and gender, as well as socioeconomic status, including family wealth and education.

“We often think about sports as level playing fields that reward people who earn their success, but that’s not the whole ...