(Press-News.org)

Siberia, a province located in Russia, is a significant geographical region playing a crucial role in the world’s carbon cycle. With its vast forests, wetlands, and permafrost regions (permanently frozen grounds), Siberia stores a considerable amount of carbon on a global scale. But climate change is rapidly altering Siberia’s landscape, shifting its vegetative distribution and accelerating the permafrost thaw. Classifying land cover is essential to predict future climatic changes, but accumulating land cover data in regions like Siberia is challenging due to the limited availability of ground observation data.

In a step towards advancing climatic studies, a recent study led by Professor Kazuhito Ichii from the Center for Environmental Remote Sensing and Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Chiba University, Japan, unveils a refined land cover map for Siberia. By leveraging multiple sources and applying a random forest classifier (a machine learning algorithm), the team addresses the inconsistencies between existing land cover datasets with a remarkable accuracy of 85.04%. The study was conducted in collaboration with Nagoya University, Japan, and was published in Volume 12, Issue 3 of the Progress in Earth and Planetary Science on January 6, 2025.

Prof. Ichii discusses the motivation for this study by saying, “While working for the Pan-Arctic Water-Carbon Cycles project, we were surprised to find major differences among existing land cover datasets, even in the widely used data sets. It was then clear that a more reliable dataset was needed, which led us to carry out this research.”

The researchers started by comparing various global datasets and then used various data points to ensure an accurate land classification. The newly developed map gave a clearer picture of the forests, wetlands, and permafrost areas, which are key elements in climate studies. When compared with the previous datasets, the researchers observed major errors in the previous sets, especially in the high-latitude regions, which could potentially lead to incorrect climate predictions.

Addressing the discrepancies in land classification, the new dataset enabled more accurate assessments of carbon flux and ecosystem changes. “By focusing on land cover, something previously thought to be well understood, we have created better data for an area that was not well characterized, opening doors for improved climatic predictions,” says Ms. Munseon Beak from the Graduate School of Science and Engineering and Center for Environmental Remote Sensing at Chiba University.

The implications of this study are extensive. By providing a more accurate land cover dataset, the research can enhance climate models with better predictions of environmental changes.

Assistant Professor Yuhei Yamamoto from the Institute of Advanced Academic Research and Center for Environmental Remote Sensing, Chiba University, emphasizes, “By integrating multiple data sources and enhancing classification accuracy, we aim to provide essential insights for climate scientists. This is particularly crucial given the rapid climatic changes occurring in Siberia.”

Siberia is greatly affected by climate change, such as global warming, resulting in major changes such as the Siberian Taiga moving northwards and the surface of the earth changing due to the thawing of permafrost. The refined land cover data would, therefore, help scientists monitor these major changes, serving as a foundational tool for predicting and managing these changes in the coming decades. These datasets also support carbon cycle assessments, which are crucial for understanding greenhouse gas dynamics and environmental studies.

Additionally, the study determined the factors that can affect the distribution of vegetation in a particular region. Professor Tetsuya Hiyama from the Institute for Space-Earth Environmental Research, Nagoya University, notes: “We have used geographical distribution analysis across different climates to understand how the distribution of vegetation gets affected. This led us to the fact that precipitation plays a major role in vegetation patterns, especially during warm summer climates."

Therefore, these datasets could also offer valuable guidance for policymakers. Aiding in sustainable land management and conservation efforts, the findings can contribute to disaster risk management, helping mitigate the impacts of permafrost thaw, wildfires, and habitat loss in the coming years.

About Professor Kazuhito Ichii from Chiba University, Japan

Professor Kazuhito Ichii is a distinguished professor and a skilled researcher specializing in terrestrial biosphere monitoring and modeling. He has more than 90 publications to his credit contributing to the fields of Bio-geoscience, Earth Systems, and Terrestrial Remote Sensing. Throughout his career, he has held notable positions, including Research Scientist at NASA Ames Research Center, Senior Researcher at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, and the Chair of AsiaFlux. Currently, he is working as a Professor at Chiba University's Center for Environmental Remote Sensing (CEReS).

END

Life has evolved over billions of years, adapting to the changing environment. Similarly, enzymes—proteins that speed up biochemical reactions (catalysis) in cells—have adapted to the habitats of their host organisms. Each enzyme has an optimal temperature range where its functionality is at its peak. For humans, this is around normal body temperature (37 °C). Deviating from this range causes enzyme activity to slow down and eventually stop. However, some organisms, like bacteria, thrive in extreme environments, such as hot springs or freezing polar waters. These extremophiles have enzymes adapted to function in harsh conditions.

For ...

Obesity is linked to numerous health complications, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and fatty liver disease. In a world where obesity rates continue to climb, researchers are constantly seeking effective, accessible solutions to this global health crisis. Interestingly, over the past few decades, scientists have begun to focus not only on what we eat but also on how we eat it.

While much attention has indeed focused on dietary content and caloric intake, emerging research suggests that eating behaviors—including meal duration, chewing speed, and number of bites taken—may ...

A new study published in The Journal of Immunology found that a high-salt diet (HSD) induces depression-like symptoms in mice by driving the production of a protein called IL-17A. This protein has previously been identified as a contributor to depression in human clinical studies.

“This work supports dietary interventions, such as salt reduction, as a preventive measure for mental illness. It also paves the way for novel therapeutic strategies targeting IL-17A to treat depression,” shared Dr. Xiaojun Chen, a researcher at Nanjing ...

Along with nitrogen and carbon, phosphorus is an essential element for life on Earth. It is a central component of molecules such as DNA and RNA, which serve to transmit and store genetic information, and ATP (adenosine triphosphate), which cells need to produce energy.

Phosphorus may also have played a key role in the origin of life. Certain conditions are needed to trigger the start of the biochemical processes that precede life. One of these is the presence of sufficient phosphorus. Its availability regulates the growth and activities of organisms. Unlike nitrogen or carbon, however, phosphorus is relatively ...

The findings come from the most comprehensive computer model of brain metabolism to date, which incorporates more than 16,800 biochemical interactions between proteins and chemicals across brain cells, supporting cells, and the blood.

Scientists can now use this open-source model to find ways to prevent age-related diseases, such as dementia.“This study provides an x-ray view into the battery that powers the brain,” said Henry Markram, Professor of Neuroscience at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland, the senior author of the study. “We can now track ...

A full slide deck of findings is available at the Box link here

TAMPA, Fla. (March 18, 2025) – A groundbreaking new study of young people’s digital media use has revealed surprising results, including evidence that smartphone ownership may actually benefit children.

The study also suggests a link between social media posting and various negative outcomes, as well as data connecting cyberbullying to depression, anger and signs of dependence on digital media.

The Life in Media Survey, led by a team of researchers at the University of South Florida in collaboration with The Harris Poll, conducted a survey of ...

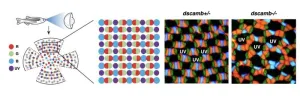

In vertebrate retinas, specialized photoreceptors responsible for color vision (cone cells) arrange themselves in patterns known as the “cone mosaic”. Researchers at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) have discovered that a protein called Dscamb acts as a "self-avoidance enforcer" for color-detecting cells in the retinas of zebrafish, ensuring they maintain perfect spacing for optimal vision. Their findings have been published in Nature Communications.

Solving a mystery in vision science

Vertebrate retinas contain photoreceptor cells that convert light into neural signals. These photoreceptors come in two main types: rods, which function ...

The standard model of particle physics is our best theory of the elementary particles and forces that make up our world: particles and antiparticles, such as electrons and positrons, are described as quantum fields. They interact through other force-fields, such as the electromagnetic force that binds charged particles.

To understand the behaviour of these quantum fields and with that our universe, researchers perform complex computer simulations of quantum field theories. Unfortunately, many of these calculations are too complicated for even our best supercomputers and pose great challenges for quantum computers as well, leaving many pressing ...

Artificial intelligence can improve intravenous nutrition for premature babies, a Stanford Medicine study has shown. The study, which will publish March 25 in Nature Medicine, is among the first to demonstrate how an AI algorithm can enable doctors to make better clinical decisions for sick newborns.

The algorithm uses information in preemies’ electronic medical records to predict which nutrients they need and in what quantities. The AI tool was trained on data from almost 80,000 past prescriptions for intravenous nutrition, which was linked to information about how the tiny patients fared.

Using AI to help prescribe IV nutrition could reduce medical errors, ...

A new study provides fresh insight into traditional acid-base chemistry by revealing that the mutual neutralization of isolated hydronium (H₃O⁺) and hydroxide (OH⁻) ions is driven by electron transfer rather than the proton transfer that is expected in bulk liquid water. Using deuterated water ions and advanced 3D coincidence imaging of the neutral products, researchers found two electron-transfer mechanisms that produce hydroxyl radicals (OH), which are crucial in atmospheric chemistry. These findings reshape our understanding ...