(Press-News.org) WOODS HOLE, Mass. -- Humans like to think that being multicellular (and bigger) is a definite advantage, even though 80 percent of life on Earth consists of single-celled organisms – some thriving in conditions lethal to any beast.

In fact, why and how multicellular life evolved has long puzzled biologists. The first known instance of multicellularity was about 2.5 billion years ago, when marine cells (cyanobacteria) hooked up to form filamentous colonies. How this transition occurred and the benefits it accrued to the cells, though, is less than clear.

This week, a study originating from the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) presents a striking example of cooperative organization among cells as a potential force in the evolution of multicellular life. Based on the fluid dynamics of cooperative feeding by Stentor, a relatively giant unicellular organism, the report is published in Nature Physics.

“We took a step back in evolution, to when organisms were independent. Why did they even come together in a colony before they ever became fixed in position relative to each other?” says John Costello of Providence College, senior author on the study and an MBL Whitman Center scientist along with co-author Sean Colin of Roger Williams University.

“So much work on the origin of multicellular life focuses on chemistry. We wanted to investigate the role of physical forces in the process,” says lead author Shashank Shekhar, Assistant Professor of Physics at Emory University and a former Whitman Center Early Career Awardee at MBL.

Many mouths are better than one

Stentor is a trumpet-shaped, single-celled organism that can grow up to 2 mm long. In its native habitat of ponds or lakes, Stentor attaches its slender end (called the holdfast) to leaves or twigs while the trumpet end sways freely, creating a vortex of water to suck in food, such as bacteria, with its cilia-lined mouth.

In the lab, the scientists noted, when Stentors are dropped into a dish of pond water, they quickly form a dynamic colony where the cells don’t actually attach to one other, but their holdfasts touch together on the glass. By quantifying fluid flows, the team showed that two neighboring Stentors in a colony can double the flow rate of water into their mouths, as compared to their individual capacity. This allows them to suck in more prey and faster-swimming prey, by creating stronger vortexes that sweep in water from a greater distance.

“She loves me, she loves me not”

However, the feeding benefits accrued by two neighboring Stentor aren’t equal, the team found. The weaker Stentor gains more from teaming up than the stronger one does. And, curiously, they display what Shekhar calls “she loves me, she loves me not” behavior. When paired Stentors sway their trumpet ends together, their fluid flows increase, but then they invariably oscillate, pulling their mouths apart again. Why?

To answer this, they turned to mathematical modeling of fluid dynamics across the colony led by co-authors Hanliang Guo of Ohio Wesleyan University and Eva Kanso of University of Southern California.

Guo and Kanso confirmed a “promiscuity” in the colony, where individuals keep switching between neighboring partners. And the result is all the cells in a Stentor colony, on average, gain stronger feeding flows.

“In a colony, even though an individual might appear to be moving away from one neighbor, it is actually moving closer to another neighbor,” the team writes. This makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint, “as individuals are expected to seek the most favorable energetic payoff by associating with a neighboring individual that benefits them most.”

“You might look at them as always attempting to optimize their income,” Costello says. And the colony as a whole reaps more food.

Just a phase

But wait. The Stentor we know and love today is not multicellular. The colonies it forms are ephemeral; they disperse just by bumping the lab table. If the individuals collectively benefit from working together, why do they separate again?

The scientists don’t know for sure. But they’ve noted that when they give Stentors plenty of food, they are happy to remain attached to the glass and feed in colonies. But when the food is taken away and becomes scarce, the Stentors detach and go into individual foraging mode.

“Humans do that, too,” Shekhar says. “When there are plenty of resources and prey, we collaborate and cooperate. But when the resources reduce, it’s each one to its own.”

We are not clones

In other models of early multicellular life, such as the green algae Volvox cateri, cells that failed to divide properly eventually evolved a matrix between them, forming a colony of genetically identical cells which later differentiated. But the ephemeral Stentor colonies are formed not of clones, but of genetically distinct individuals.

That’s why the scientists think their Stentor model precedes other models of early multicellularity (which is believed to have evolved at least 25 times in different lineages).

“This is earlier, much earlier in evolution where happy single cells said, OK, let’s hang out together and benefit, but then let’s go back to being single again. Multicellularity wasn’t done permanently yet,” says Shekhar.

Shekhar began this study as a student in the 2014 MBL Physiology course with then course co-director Wallace Marshall of University of California, San Francisco, an expert on Stentor.

—###—

The Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) is dedicated to scientific discovery – exploring fundamental biology, understanding marine biodiversity and the environment, and informing the human condition through research and education. Founded in Woods Hole, Massachusetts in 1888, the MBL is a private, nonprofit institution and an affiliate of the University of Chicago.

END

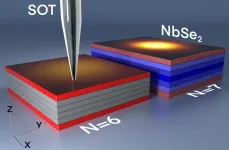

Researchers have discovered an unexpected superconducting transition in extremely thin films of niobium diselenide (NbSe₂). Published in Nature Communications, they found that when these films become thinner than six atomic layers, superconductivity no longer spreads evenly throughout the material, but instead becomes confined to its surface. This discovery challenges previous assumptions and could have important implications for understanding superconductivity and developing advanced quantum technologies.

Researchers at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have made a surprising discovery about how superconductivity ...

Researchers have developed new AI models that can vastly improve accuracy and discovery within protein science. Potentially, the models will assist the medical sciences in overcoming present challenges within, e.g. personalised medicine, drug discovery, and diagnostics.

In the wake of broadly available AI tools, most technical and natural sciences fields are advancing rapidly. This is particularly true in biotechnology, where AI models power breakthroughs in drug discovery, precision medicine, gene editing, food security, and many other research areas.

One sub-field is proteomics – the study of proteins on a large scale – where ...

A newly developed blood test for Alzheimer’s disease not only aids in the diagnosis of the neurodegenerative condition but also indicates how far it has progressed, according to a study by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Lund University in Sweden.

Several blood tests for Alzheimer’s disease are already clinically available, including two based on technology licensed from WashU. Such tests help doctors diagnose the disease in people with cognitive symptoms, but do not indicate the ...

Plate temperature and water release can explain the occurrence of different types of earthquakes in Guerrera, Mexico. The Kobe University simulation study also showed that the shape of the Cocos Plate is responsible for a gap where earthquakes haven’t occurred for more than a century. The results are important for accurate earthquake prediction models in the region.

Where one tectonic plate is pushed down by another, the resulting stress is released in various tectonic events. There are catastrophic megathrust earthquakes, unnoticeable “slow slip events,” and continuous low-frequency “tectonic tremors,” and knowing ...

Scientists have found another reason to put the phone down: a survey of 45,202 young adults in Norway has discovered that using a screen in bed drives up your risk of insomnia up by 59% and cuts your sleep time by 24 minutes. However, social media was not found to be more disruptive than other screen activities.

“The type of screen activity does not appear to matter as much as the overall time spent using screens in bed,” said Dr Gunnhild Johnsen Hjetland of the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, ...

In the face of major changes to federal policy and funding in the United States, Canada should support Canadian researchers with adequate funding to ensure long-term research in health and science, argue authors in two articles published in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

“As the US stands on the brink of tearing down its exemplary system for covering the full costs of research, Canada, with its flawed federal system for indirect costs, should heed the recent commissioned science policy report and a chorus of advocacy calling for an enhanced indirect cost system,” writes Dr. William Ghali, vice-president ...

Cannabis use has been increasing during pregnancy, according to researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and the Columbia University Irving Medical Center. Previous research has observed that past-month cannabis use has more than tripled among pregnant women in the U.S. from 2002-2020 with self-reported cannabis use rising from 1.5 percent to 5.4 percent over the 18 years of tracking data. The findings are published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

Medical guidelines recommend that pregnant women abstain from cannabis because of its link to an increased risk of adverse maternal ...

The UK education system must urgently change to be more understanding of school ‘refusers’, as returning to school might not be the right outcome for some children, psychologists say.

While much has been made of school attendance figures in recent months, a group of experts are suggesting not enough attention has been given to the experiences of parents and young people experiencing school distress.

In a new book, What Can We Do When School’s Not Working?, a parent and two ...

Play should be a core feature of children’s healthcare in forthcoming plans for the future of the NHS, according to a new report which argues that play “humanises” the experiences of child patients.

The report, by University of Cambridge academics for the charity Starlight, calls for play, games and playful approaches to be integrated into a ‘holistic’ model of children’s healthcare – one that acknowledges the emotional and psychological dimensions of good health, ...

Banks facing regulatory sanctions for financial misconduct tend to adopt riskier business practices, according to new research.

The authors warn repeated or systemic misconduct can accelerate risk-taking in ways that weaken both individual institutions and the wider financial system.

Researchers from the University of East Anglia (UEA), the US Department of the Treasury and Bangor University, in the UK, drew on data from nearly 1,000 publicly listed US banks from 1998 to 2023 - a period spanning multiple economic cycles including the 2007–09 ...