Commonly called the “corpse flower,” Amorphophallus titanum is endangered for many reasons, including habitat destruction, climate change and encroachment from invasive species.

Now, plant biologists from Northwestern University and the Chicago Botanic Garden have added a new threat to the list: incomplete historical records.

In a new study, scientists constructed the ancestry of corpse flowers living in collections at institutions and gardens around the world. They found a severe lack of consistent, standardized data. Without complete historical records, conservationists were unable to make informed decisions about breeding. Of the corpse flowers studied, therefore, 24% were clones and 27% were offspring from two closely related individuals.

The study will be published on April 3 in the Annals of Botany.

“There are many risks associated with low genetic diversity,” said Olivia Murrell, who led the study. “Decreasing genetic diversity over time leads to a decrease in fitness. Generally speaking, inbred plants might not produce as much pollen or might die right after they flower. One institution reported that, possibly as a result of inbreeding, all their corpse flower offspring were albino, so they didn’t survive because they didn’t have chlorophyll to photosynthesize. The population as a whole also doesn’t have the variation it needs to survive. So, if a disease or pest affects plants that are all genetically similar, all plants in that population are more likely to suffer. We don’t think people are consciously making the choice to inbreed their plants. They just don’t know what they have because the data are incomplete.”

At the time of the study, Murrell was a master’s student in plant biology in the Program in Plant Biology and Conservation, a partnership between Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and the Chicago Botanic Garden. Now she is a Ph.D. student at Manchester Metropolitan University in the U.K. and a conservation scholar at the Chester Zoo. Senior authors from the Program in Plant Biology and Conservation are Jeremie Fant, Nyree Zerega and Kayri Havens. Fant, Zerega and Havens also are conservation scientists with the Negaunee Institute for Plant Conservation Science and Action at the Chicago Botanic Garden.

A finicky flower

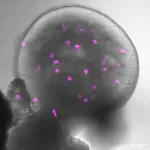

Nicknamed for its smell, the corpse flower emits an odor that mimics rotting flesh when it blooms. A clever evolutionary trick, the pungent odor attracts flies and carrion beetles, the plant’s primary pollinators. Because the bloom is rare and short-lived — lasting just 24 to 48 hours — gardens often hold events for visitors to experience the infamous stench firsthand.

“Usually, you have to get close to a flower to be able to smell it,” Murrell said. “That is not true for the corpse flower. The second you walk into its greenhouse, its smell smacks you across the face. It’s very strong. The plant also heats up when it blooms, which spreads its smell farther.”

Gardens go to great lengths to care for these charismatic companions. The corpse flower is one of several “exceptional plants,” a designation given to species whose seeds cannot be effectively conserved in seed banks. In the corpse flower’s case, its seeds are no longer viable after drying, which is a necessary step for long-term seed storage. Instead, corpse flowers and other exceptional plants are conserved in “living collections” within research facilities, botanic gardens and arboreta.

Because male and female corpse flowers bloom at different times, the flowers in these living collections rely on humans to keep their lineages alive. Their caretakers, however, face several challenges.

“The female flowers open first, and then the male flowers open later,” Murrell said. “So, the female flowers are no longer viable by the time pollen is produced. The plant also blooms rarely and unpredictably. It could go seven to 10 years without blooming. Then, when the blooms do open, the female flowers are only viable for a couple hours. With that limited time to pollinate, conservationists scramble to use whatever they have on hand. That might be pollen from a previous flower on the same individual, which results in inbreeding.”

Wilted records

To better understand what happens in these situations, Murrell located all the living collections around the world which contained corpse flowers. Ultimately, she received data from nearly 1,200 individual plants from 111 institutions across North America, Asia, Australia and Europe. The data arrived in the forms of handwritten notes, prose, lists and spreadsheets.

Ideally, a plant’s records should contain detailed information about its origin, parents, characteristics, health and propagation. Crucial for conservation efforts, these data help conservationists maintain genetic diversity and plant health while preventing loss. Without this information, people cannot make informed decisions about which plants to cross for breeding.

After organizing all the information received from institutions, Murrell found it was severely lacking. Institutions often did not record the sources and origins of individual plants. Even when they did record seed sources, they did not record information about which plant’s pollen was used for breeding.

“The highest rate of missing data occurred when plants were transferred to new locations,” Murrell said. “The plants moved, but their data didn’t move with them. So, records easily got lost over time as plants moved around.”

Clones and crosses

To determine prevalence of inbreeding, Murrell and her team examined the records for clones and breeding between related plants. Of the 1,188 individual plants in the dataset, 287 (24%) were clones and 27% were offspring from closely related individuals. Fewer than one-third of crosses occurred between unrelated individuals.

Looking to substantiate these conclusions, Murrell performed a small molecular genetics study on 65 plants. By sequencing the plants’ DNA, the team confirmed low genetic diversity and high inbreeding across all collections.

Native only to Sumatra, the corpse flowers’ numbers continue to decline. According to a recent estimate published in the journal Biodiversity and Conservation, just 162 individual corpse flowers remain in the wild. The dwindling population underscores the need to ensure these plants can thrive in living collections, so they eventually can be reintroduced into the wild.

“The population needs variation to survive,” Murrell said. “If nothing changes, it could inbreed itself into extinction. That’s why it’s really important to keep consistent, standardized and centralized data. Not keeping data has clear conservation implications. In the meantime, our study provides valuable information about relationships among existing collections, which can be used to determine which crosses might be most successful.”

To help improve collections of corpse flowers and other species, Murrell and her coauthors made five recommendations. They urged institutions to (1) document parents and destinations of plants sampled in the wild, (2) standardize data across collections, (3) track parent plants across institutions, (4) transfer data with plants when they are moved to new institutions and (5) determine common language for recordkeeping so all definitions are consistent.

The study, “Using pedigree tracking of the ex situ metacollection of Amorphophallus titanium to identify challenges to maintaining genetic diversity in the botanical community,” was supported by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the Northwestern University Plant Biology and Conservation Award, a Botanical Society of America Graduate Student Research Award and The Walder Foundation.

END