(Press-News.org) Comprehensive reference genomes have now been assembled for six ape species: siamang (a Southeast Asian gibbon), Sumatran orangutan, Bornean orangutan, gorilla, bonobo and chimpanzee. Areas of their genomes previously inaccessible because of structural complexity have now mostly been resolved.

The resource is already lending itself to comparative studies that offer new insights into human and ape evolution, and into what underlies the functional differences among these species.

A report on how the telomere-to-telomere ape genome references were developed, and what scientists are learning from it, appears in the April 9 edition of Nature.

The senior researchers and corresponding authors on this international, multi-institutional project were Evan E. Eichler, professor of genome sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle and an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute; Kateryna D. Makova of the Department of Biology, Penn State University; Adam M. Phillippy of the National Human Genome Institute at the National Institutes of Health. The lead author is DongAhn Yoo, a postdoctoral fellow in the Eichler lab.

“These ape genomes will enable us to reconstruct the evolutionary history of every base pair in our genome,” Eichler said.

He described the project as a massive team effort with over 40 research labs and over 120 scientists from around the world working years to assemble, quality control, and analyze these genomes.

The scientists on this project estimate that each of the recent genome assemblies is more than 99% resolved, including the most difficult bits. These polished versions have significantly improved the sequencing accuracy of previous ape genome assemblies and are comparable to the quality of the most recent human genome references. This eliminates some of the biases from previous comparisons in which the human genome assemblies were always superior.

The researchers also constructed a 10-way pangenome to compare all six ape genomes plus four human genomes. It is accompanied by an interspecies graph.

The latest findings, for instance, reveal some genetic distinctions among humans and apes in such areas as the immune system, longevity and brain development. This knowledge may have biomedical relevance in fields like aging, speech acquisition, neuropsychiatry and immunology.

Human-like apes split off from chimps about 5.5 to 6.3 million years ago. Chimps, along with bonobos, are our nearest living primate relatives. It is widely reported that chimps and humans share 99% of their genomes, but in-depth comparisons point to subtle nuances. These might help explain why chimps and humans aren’t more alike. The genomes of the two species don’t quite align, particularly in certain regions

African apes, our next closest kin on the primate ancestral tree, diverged about 10.6 to 10.9 million years ago, and orangutans some 18.2 to 19.6 million years ago. The new ape genome resource is proving useful in analyzing the mechanisms involved in ape speciation – how new species evolve from existing ones – and calls into question prevailing views about how various ape species came into being.

Other explorations of the ape reference genomes have led to unexpected findings of potential therapeutic significance. For example, the evolution of much smaller but fully functional centromeres (involved in controlling cell division) in bonobos may offer ideas for engineering streamlined artificial chromosomes to transmit genetic information into human cells to treat or prevent disease.

In additional analyses of the ape genomes, scientists systematically worked to pinpoint the most rapidly evolving regions in each primate species. These are areas with an accelerated rate of mutations often associated with the emergence of new genes that are specific to one species.

One of the most structurally diverse, gene-rich regions is the major histocompatibility complex. This is a huge cluster of genes that code for the cell-surface proteins that enable the body’s immune system to distinguish between its harmless self and potentially harmful intruders. This region varies greatly among mammals. When compared with the human genome, this region shows that ancient, species-specific differences may be key to understanding a number of diseases that affect only people.

In examining great ape genetic diversity, the researchers looked for genomic signatures that suggested adaptation. Besides enrichment in areas implicated in immune function and in the formation of the outer skin, there are pathways associated with brain development and diet. These include sensory perception for tasting bitterness, the breaking down of lipids like fats and oils, and the movement of iron within the body.

Assessments of what evolutionary genome scientists call “Ancestor Quickly Evolving Regions” found that there were more than double the number of previously discovered regions of this type in humans. Usually, but not always, these areas are characterized by highly repetitive DNA.

One example of such an area is a gene associated with a type of brain cell found in a brain area linked to talking and located in the motor cortex. This gene is analogous to one that plays a role in vocal learning centers in songbirds and governs song production. Humans have a unique genetic control element in the middle of this Human Ancestor Quickly Evolving Region.

Of special interest to human and ape evolutionary studies are repeats in the DNA code called segmental duplications. Earlier genome sequencing studies failed to completely characterize these regions. Technical advances in long-read sequencing made these regions accessible for the first time.

Segmental duplications are one of the ways that gene innovations originate. They appear to play a major role in genetic variation among apes, including dramatic restructuring of large portions of the chromosomes.

Segmental duplications are enriched in the short arms of certain types of chromosomes that are joined, not in the middle, but off-center so that their arms are of different lengths. Examples of these so-called acrocentric chromosomes are chromosomes 13, 14, 15, 21 and 22.

Acrocentric chromosomes are unusual in other ways that contribute to differences among ape species. Compared with other chromosomes, there are excessive repeating sequences and recombinations on the short arms of these acrocentric chromosomes.

Orangutans have more acrocentric chromosomes than other apes, the researchers explained. They also have the greatest number of segmental duplications in comparison to the African great apes. Chimps, bonobos and gorillas, but not siamangs, have more segmental duplications than humans and other primates do.

For the first time, researchers have been able to study the genetic sequence, structure and evolution of the centromere regions at the level of the basic building blocks of their DNA: the base pairs. They also report the differences between the centromere structures and sizes in chimp and bonobo. Bonobos and chimps diverged about 1.8 million years ago, after they were geographically separated by the Congo River and followed their own evolutionary routes. Although the bonobo centromeres are remarkably smaller than those of the chimp, they function fine.

More generally, analyzing segmental duplication allows scientists to determine which are lineage-specific to each ape species. Using the new resources, researchers are attempting to sort out, by location and composition, the segmental duplications that pertain to each species.

“We now have an evolutionary framework for understanding highly divergent, previously inaccessible regions of the ape genome,” the researchers wrote in their Nature paper. Such studies also uncover genomic constructions that are prone to reshuffling.

“Segmental duplication rearrangements may be a greater source than previously realized of interspecies differences and potential gene neofunctionalization,” the scientists noted.

Most evolutionary biologists believe that the differences that distinguish humans from chimpanzees are regulatory in origin — slight changes in where and when highly conserved genes are expressed. The ape genomes reference is providing a new model.

“We are discovering hundreds of protein-coding genes embedded in these segmental duplications that are unique to each ape species,” said Eichler. “Some of these have already been shown to contribute to changes that make us uniquely human, such as a bigger brain.”

The new results suggest that there are many more protein-encoding differences among the apes.

Acquiring more information on segmental duplication rearrangements may help researchers make headway in determining how certain conditions in humans, for example, developmental delay, intellectual impairments and autistic traits, stem from new mutations that might form in this manner.

While they believe that the ape genome samples are almost fully complete, the scientists said that there is still work to be done, including filling in a few of the last remaining complex gaps. Additionally, about 15 species and subspecies of apes remain to have their genomes sequenced and added to the reference resource.

The scientists say they also hope to eliminate biases in gene annotation that favor humans over the other ape species. Mapping genes onto genomic sequences and predicting the functional genes is challenging. Nonetheless, research has been impeded by ignoring potentially significant, but less studied, genes.

END

Six ape genomes sequenced telomere-to-telomere

A definitive reference has become openly available for comparative evolutionary studies of humans and the apes closest to us on the tree of life

2025-04-09

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Hubble Space telescope unveils the first images of ongoing star cluster mergers near the center of dwarf galaxies

2025-04-09

A new study reports the first direct observation of merging star clusters in the nuclear region of dwarf galaxies. This detection confirms the feasibility of this formation route for nuclei in dwarf galaxies, which has long been debated. The study was published in Nature science journal, and led by Postdoctoral Researcher Mélina Poulain from the University of Oulu, Finland.

Dwarf galaxies are the most abundant type of galaxies that populate the Universe. Composed of 100 times fewer stars than the ...

‘Sugar’ signatures help identify and classify pancreatic cancer cell subtypes

2025-04-09

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (April 9, 2025) — Van Andel Institute scientists and collaborators have developed a new method for identifying and classifying pancreatic cancer cell subtypes based on sugars found on the outside of cancer cells.

These sugars, called glycans, help cells recognize and communicate with each other. They also act as a cellular “signature,” with each subtype of pancreatic cancer cell possessing a different composition of glycans.

The new method, multiplexed glycan immunofluorescence, combines ...

Every cloud has a silver lining: DeepSeek’s light through acute respiratory distress syndrome shadows

2025-04-09

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) continues to be a tough nut to crack in critical care, taking lives despite years of research and better ventilator strategies. It is defined by acute hypoxemia, bilateral infiltrates on chest imaging, and non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema, and it remains a heterogeneous condition with mortality rates stubbornly close to 40%. Its complexity—spanning diverse etiologies, inflammatory profiles, and therapeutic responses—demands innovative solutions beyond traditional paradigms. In recent years, artificial intelligence ...

Scientific Program announced for inaugural eLTER Science Conference in Finland

2025-04-09

The scientific programme for the inaugural eLTER Science Conference has just been launched, marking a major milestone in the lead-up to the event. Held from 23 to 27 June 2025 in Tampere, Finland, the conference will explore integrated, policy-relevant approaches to ecosystem and socio-ecological research under the theme: “Toward a whole-system approach to ecosystem science.”

Organised by the Integrated European Long-Term Ecosystem, critical zone and socio-ecological systems Research Infrastructure (eLTER RI), the event is expected to welcome over 300 participants from across Europe and beyond.

The scientific programme features:

25 keynote speakers recognised for their leadership ...

Does blastocyst size matter? Exploring reproductive aging and genetic testing

2025-04-09

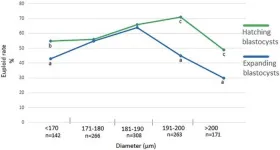

“[…] when selecting non-PGT-A tested embryos for embryo transfer (ET) or frozen embryo transfer (FET), a small hatching blastocyst seems to be a better choice than a large expanded one, especially for advanced-age patients for whom the risk of aneuploidy is higher.”

BUFFALO, NY — April 9, 2025 — A new research paper was published in Aging (Aging-US) Volume 17, Issue 3, on March 5, 2025, titled “Reproductive aging, preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy, and the diameter of blastocysts: does size matter?”

In this study, a team led by first author Jakub Wyroba from the Malopolski Institute of Fertility Diagnostics ...

2025 EurekAlert! Travel Awards for International Science Reporters applications now open

2025-04-09

Applications for the 2025 EurekAlert! Travel Awards for International Science Reporters are now open to early-career science journalists from Brazil and countries in Eastern Europe. Two winners will be selected to receive travel funding from EurekAlert! to attend the 2026 AAAS Annual Meeting, taking place February 12-14, 2026 in Phoenix, Arizona, USA. Learn more about who is eligible and how to apply on our website. The application deadline is May 5 at 11:59 p.m. U.S. Eastern Time.

Learn More and Apply!

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is the world’s largest multidisciplinary scientific society, and the AAAS Annual Meeting brings together ...

Menstrual cycle may contribute to sickle cell disease pain crises

2025-04-09

(WASHINGTON— April 9, 2025) — A marker linked to inflammation, C-reactive protein, may increase significantly during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle in female patients with sickle cell disease (SCD), according to emerging research published today in Blood Vessels, Thrombosis & Hemostasis. This observation provides insight into the pattern of painful vaso-occlusive events (VOEs), which are driven by inflammation, in female patients with the disorder.

“We know both from the literature and anecdotally from our patients that women with SCD have VOEs that cluster ...

PolyU scholar unveils research on long-term effects of obesity on brain and cognitive health

2025-04-09

With the global prevalence of obesity on the rise, it is crucial to explore the neural mechanisms linked to obesity and its influence on brain and cognitive health. However, the impact of obesity on the brain is complex and multilevel. To address this, Prof. Anqi QIU, Professor of the Department of Health Technology and Informatics at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) and Global STEM Scholar, has unveiled novel research to advance our understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying the relationship between obesity and its implications for cognitive health in adults.

Obesity ...

Comprehensive Keck Medicine of USC medical office building coming soon to Pasadena

2025-04-09

LOS ANGELES — Keck Medicine of USC will open a four-story, 100,000 square-foot, state-of-the-art medical office building located at 590 S. Fair Oaks Ave. in Pasadena in fall 2025.

As the newest addition to the renowned academic health system, the location will significantly expand Keck Medicine clinical care for residents of Pasadena and neighboring communities in the San Gabriel Valley.

What sets the new Pasadena location apart

“This new location — our largest and most advanced outpatient setting — will ...

Contagious quitting? New USF-led study links peer behavior to employee turnover

2025-04-09

TAMPA, Fla. (April 9, 2025) – A new study led by the University of South Florida and the University of Cincinnati sheds light on the powerful impact of workplace cohorts on newcomer retention. The findings provide critical insights for organizations seeking to reduce employee turnover and improve stability among their teams.

Cohorts, groups of new employees that join an organization at the same time and are usually trained together, are common in the military and in professional services such as law, accounting and consulting firms. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal reports faster robot-assisted brain angiography

New study clarifies how temperature shapes sex development in leopard gecko

Major discovery sparks chain reactions in medicine, recyclable plastics - and more

Microbial clues uncover how wild songbirds respond to stress

[Press-News.org] Six ape genomes sequenced telomere-to-telomereA definitive reference has become openly available for comparative evolutionary studies of humans and the apes closest to us on the tree of life