(Press-News.org) In a discovery that may lead to a new treatment for breast cancer that has spread to the bone, a Princeton University research team has unraveled a mystery about how these tumors take root.

Cancer cells often travel throughout the body and cause new tumors in individuals with advanced breast cancer -- a process called metastasis -- commonly resulting in malignant bone tumors. What the Princeton research has uncovered is the exact mechanism that lets the traveling tumor cells disrupt normal bone growth. By zeroing in on the molecules involved, and particularly a protein called "Jagged1" that sends destructive signals to cells, the research team has opened the door to drug therapies that could block this disruptive process. Doctors at other medical centers who have reviewed the research have found it promising.

"Right now we don't have many treatments to offer these patients," said Yibin Kang, an associate professor of molecular biology at Princeton who led the research team. "Doctors can manage the symptoms of this bone cancer, but they can't do much more. Our findings suggest there could be a new way of treatment," one that could slow or halt these bone tumors.

Breast cancer spreads to the bone in 70 to 80 percent of patients with advanced breast cancer, and it can also spread to the brain, lung and liver. Metastatic bone cancer is also a frequent occurrence among patients with advanced prostate, lung and skin cancers. In findings that will be published online in the journal Cancer Cell on Feb. 3, the team's research shows that breast tumor cells are able to give bone cells the wrong instructions through a process known as cell signaling -- with disastrous effects for the patient.

The billions of cells in a living human body must communicate to develop, repair tissue, and effectively maintain normal physiological functions. Cell signaling is part of a complex system that enables them to do that but, in patients with cancer, the relationship between signaling molecules and the molecules that communicate with them has gone awry.

Signaling molecules are those that can be received and read by a cell through a receptor molecule on its surface. Once the signaling molecules connect with a receptor, their union sets off a process that leads to the receiving cell changing its behavior. The sequence of events that follows involves a signaling pathway, which is a group of molecules that work together, one molecule activating the next until a specific function is carried out, such as renewing an organ's cells. There are many such signaling pathways.

But in the case of metastatic breast cancer, a disruptive pathway is formed. The signaling molecule, also known as a ligand, connects with a receptor molecule on certain bone cells and activates a cellular pathway that ultimately disrupts healthy bone renewal. Kang's team identified the signaling molecule as Jagged1, and the receptor molecule as one that activates a cellular pathway known as the "Notch pathway."

This finding gives cancer researchers a specific target, Kang said -- that of developing ways "to neutralize Jagged1's destructive power" and keeping it from interfering with normal bone growth.

At the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, Jacqueline Bromberg, a physician who also studies breast cancer, said the findings of Kang's team are promising.

"The bone is the most common site for metastasis in patients with breast cancer," said Bromberg, who met Kang several years ago while he was a postdoctoral fellow at Sloan Kettering. She noted that although there are treatments that can slow these tumors, such as estrogen-blockers, radiation and chemotherapy, "we have few therapies which effectively eradicate bone metastasis."

At the University of Indiana School of Medicine in Indianapolis, oncology professor Theresa Guise said the Princeton discoveries "show critical interactions between the tumor cells and bone cells." She added that the team has made a valuable contribution to research in that it "has dissected the contribution of the tumor and the micro-environment in this process."

FINDING HAS LINK TO EARLIER BREAST CANCER WORK

The research builds on earlier work begun six years ago by Kang's laboratory that looked at how several different signaling pathways promote the spread of cancer to the bone. In a study published in the journal Nature Medicine in 2009, Kang showed that a pathway known as TGF beta plays a role in the growth of bone tumors. But until the recent study, it was not clear that Jagged1 plays a crucial role in that process. Before the current work focused on identifying the series of interconnected events that create the network of destructive pathways, Kang and Nilay Sethi, a dual degree student who recently finished his Ph.D. in molecular biology at Princeton, worked to find first which of the signaling molecules were at work in patients with breast cancer that had metastasized to the bone.

"It turned out that tumor samples from patients with breast cancer that had spread to the bone had higher levels of Jagged1," said Sethi, who is now completing his medical degree at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

The current research shows that, when the Jagged1 signaling molecule binds to its receptor molecule on the bone-producing cells, the interaction turns on the signaling pathway called Notch, and that leads to dramatic changes in bone growth. "It's like a key finding its matching lock, and opens a floodgate of information," Kang said. "Unfortunately, in this case, the Jagged1-Notch signaling is misused by cancer cells to serve a destructive purpose."

In healthy bone, specialized bone cells called osteoclasts scour the bone surface and use a combination of enzymes and acids to break down the old bone. Then another group of bone cells called osteoblasts deposit a new layer of bone matrix to rebuild the bone tissue. Working just like cellular excavators and paving machines, the bone-scrubbing osteoclasts and bone-building osteoblasts work in sync every day to renew the bone and maintain its strength. When these cells' activity gets out of balance, bone diseases can result.

While tumor cells lack the specialized tools that osteoclasts have to break down the bone, they are able to use the destructive Jagged1 molecule to disrupt the balanced activity of bone renewal, forcing the osteoclasts and osteoblasts to behave in a way that allows the tumor cells to invade the bone, Kang explained.

For example, by activating Notch signaling in osteoclasts, Jagged1 makes osteoclasts mature more quickly from their precursor cells, known as monocytes. A massive accumulation of these bone-scouring osteoclasts becomes the front line of the invasive force of tumor cells. That speeds up the breakdown of bone tissue and clears the way for tumor cells to expand into a malignant mass in the bone.

"Meanwhile, Jagged1 instructs the osteoblasts to secrete elevated levels of Interleukin-6, a tumor growth factor, so the cancer grows even faster," Kang said. "It's a one-two punch."

Creating further damage, the breakdown of the bone matrix releases a large quantity of another protein called TGF-beta, another signaling molecule that is embedded in the bone matrix during the bone-building process. In their earlier work published in 2009, Kang and colleagues showed that the TGF-beta protein derived from bones fuels the malignant growth of bone metastasis.

In the current study, some experiments conducted by Sethi established a surprising new link between TGF-beta and the Jagged1 molecule in bone metastasis.

"When tumor cells use the hijacked osteoclasts to break down the bone and release TGF-beta, it signals back to tumor cells to further stimulate the expression in Jagged1 in tumor cells," Sethi said. "The link between the Jagged1/Notch and TGF-beta pathways establishes a vicious cycle, essentially driving the unstoppable expansion of tumor and the destruction of skeletal tissues."

As a medical student, Sethi said he is acutely aware of the consequence of bone metastasis. "These patients suffer a lot. They have fractures, severe bone pain and debilitating nerve compression," he said. In addition, as the bone breaks down, calcium builds up in the blood, causing other life-threatening complications.

BLOCKING DESTRUCTIVE PATHWAY A POTENTIAL TREATMENT PATH

The key to stopping the process appears to be finding a way to neutralize the Jagged1 signaling molecule or its receptor Notch.

Kang has several ideas on how scientists may learn how to do just that. One way to interrupt the destructive process is to put a roadblock in the Notch pathway. There is a way to do that by halting the activity of gamma secretase -- an enzyme that plays a key role when the Notch pathway is activated --because without it the delivery of instructions to bone cells cannot be completed. The pharmaceutical firm Merck & Co. has developed one such experimental drug that stops gamma secretase, known as a gamma secretase inhibitor or GSI, and the company has provided it to Kang's lab to support his team's work.

The drug has already shown promise treating metastatic bone cancer, Kang said. In animal experiments, the inhibitors have been proven to block the disease-causing signaling between tumor cells and bone cells, communication mediated by Jagged1 and Notch. Kang said GSI can reduce bone metastasis significantly, along with a dramatic reduction of bone destruction.

He hopes his team's new data showing that GSIs appear to work to halt the spread of cancer to the bone will result in clinicians starting a clinical trial of GSI to fight breast cancer metastases in the near future.

According to Kang, there are few drugs currently available to relieve symptoms associated with bone metastases, and none is able to completely stop the cancer. If Kang's findings lead to a drug that can halt or slow this process, it could affect the 200,000 patients that the NCI estimates are diagnosed every year with breast cancer. It might work for some other cancer patients as well, Kang said.

Sloan-Kettering's Bromberg said Kang's recent discovery "underlies the importance of targeting the environmental milieu" in which disease develops, in this case the activity of the Notch signaling pathway and specific interactions between cancer cells and the specialized cells that break down and rebuild bone.

INFORMATION:

Kang's work was funded by the New Jersey Commission on Cancer Research, the San-Francisco-based Brewster Foundation founded by 1969 Princeton alumnus Leonard Schaeffer, U.S. Department of Defense, American Cancer Society, Merck & Co., the National Institutes of Health and the Champalimaud Foundation in Lisbon, Portugal.

Princeton scientists discover mechanism involved in breast cancer's spread to bone

2011-02-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Boosting body's immune response may hold key to HIV cure

2011-02-04

Australian scientists have successfully cleared a HIV-like infection from mice by boosting the function of cells vital to the immune response.

A team led by Dr Marc Pellegrini from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute showed that a cell signaling hormone called interleukin-7 (IL-7) reinvigorates the immune response to chronic viral infection, allowing the host to completely clear virus. Their findings were released in today's edition of the journal Cell.

Dr Pellegrini, from the institute's Infection and Immunity division, said the finding could lead to a cure for chronic ...

Expectations speed up conscious perception

2011-02-04

The human brain works incredibly fast. However, visual impressions are so complex that their processing takes several hundred milliseconds before they enter our consciousness. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Brain Research in Frankfurt am Main have now shown that this delay may vary in length. When the brain possesses some prior information − that is, when it already knows what it is about to see − conscious recognition occurs faster. Until now, neuroscientists assumed that the processes leading up to conscious perception were rather rigid and that ...

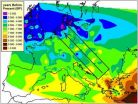

Northern hunters slowed down advance of Neolithic farmers

2011-02-04

One of the most significant socioeconomic changes in the history of humanity took place around 10,000 years ago, when the Near East went from an economy based on hunting and gathering (Mesolithic) to another kind on agriculture (Neolithic). Farmers rapidly entered the Balkan Peninsula and then advanced gradually throughout the rest of Europe.

Various theories have been proposed over recent years to explain this process, and now physicists from the University of Girona (UdG) have for the first time presented a new model to explain how the Neolithic front slowed down as ...

Adapting technology to elderly people

2011-02-04

Massive Art Multimedia in Austria and CoSi Elektronik in Germany have a history of collaboration on successful technical projects. A brainstorming session between their developers produced the idea of bringing together many aspects of the modern computing world and applying them specifically to the one group in society that is least likely to already feel those benefits - senior citizens. As with so many projects of this nature, the funding for development was out of reach of two SMEs. By facilitating the funding process EUREKA permitted the development of the project now ...

Death in the bat caves: Disease wiping out hibernating bats

2011-02-04

Conservationists across the United States are racing to discover a solution to White-Nose Syndrome, a disease that is threatening to wipe out bat species across North America. A review published in Conservation Biology reveals that although WNS has already killed one million bats, there are critical knowledge gaps preventing researchers from combating the disease.

WNS is a fatal disease that targets hibernating bats and is believed to be caused by a newly discovered cold-adapted fungus, Geomyces destructans, which infects and invades the living skin of hibernating bats. ...

Using a generic blood pressure and heart drug could save the UK $324 million in 2011

2011-02-04

Using a generic drug to treat hypertension and heart failure, instead of branded medicines from the same class, could save the UK National Health Service (NHS) at least £200 million in 2011 without any real reduction in clinical benefits.

That is the key finding of a systematic review, statistical meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness analysis just published online by IJCP, the International Journal of Clinical Practice.

Researchers from University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust looked at 14 hypertension and heart studies published between 1998 and 2009 ...

Lund adopts chromosome 19

2011-02-04

The genes that make up the human genome were mapped by HUGO, the Human Genome Organisation, and published in 2001. Now the project is expanding into the HUPO, the Human Proteome Organisation. Within the framework of this organisation, many hundreds of researchers around the world will work together to identify the proteins that the different genes give rise to in the human body.

"The 'proteome', the set of all human proteins, is significantly more complicated than the genome. There are over 20 000 proteins coded by the genome in the human body and each protein can have ...

Current use of biodiesel no more harmful than regular diesel

2011-02-04

Up to seven per cent biodiesel blended in regular diesel will presumably not cause greater health risks for the population than the use of pure fossil diesel. This is the main conclusion in a memorandum from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and the Climate and Pollution Control Agency (formerly SFT) to the Ministry of Health and Care Services and the Ministry of the Environment in Norway.

"A higher content of biodiesel (up to 20 per cent) requires more research to assess health effects. This must include different types of biofuels and blending ratios, as well ...

Blood-clotting agent can diagnose fatal genetic diseases, finds study

2011-02-04

University of Manchester scientists have shown that a protein involved in blood clotting can be used to diagnose and subsequently monitor the treatment of a group of childhood genetic diseases.

In the study, published in the Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease, the researchers were able to show that the clotting agent, heparan cofactor II/Thrombin (HCII/T) complex, could be used as a 'biomarker', or biological tell, in individuals with mucopolysaccharide (MPS) diseases.

MPS diseases are severe metabolic conditions caused by a genetic defect that affects the body's ...

Drug-abusers have difficulty to recognize negative emotions as wrath, fear and sadness

2011-02-04

University of Granada scientists have been the first to analyze the relation between drug abuse and recognition of basic emotions (happiness, surprise, wrath, fear, sadness and disgust) by drug-abusers. Thus, the study revealed that drug-abusers have difficulty to identify negative emotions by their facial expression: wrath, disgust, fear and sadness.

Further, regular abuse of alcohol, cannabis and cocaine usually affects abusers' fluency and decision-making. Consuming cannabis and cocaine negatively affects work memory and reasoning. Similarly, cocaine abuse is associated ...