(Press-News.org) "Man is but a worm" was the title of a famous caricature of Darwin's ideas in Victorian England. Now, 120 years later, a molecular analysis of mysterious marine creatures unexpectedly reveals our cousins as worms, indeed.

An international team of researchers, including a neuroscientist from the University of Florida, has produced more evidence that people have a close evolutionary connection with tiny, flatworm-like organisms scientifically known as "Acoelomorphs."

The research in the Thursday (Feb. 10) issue of Nature offers insights into brain development and human diseases, possibly shedding light on animal models used to study development of nerve cells and complex neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

"It was like looking under a rock and finding something unexpected," said Leonid L. Moroz, a professor in the department of neuroscience with the UF College of Medicine. "We've known there were very unusual twists in the evolution of the complex brains, but this suggests the independent evolution of complex brains in our lineage versus invertebrates, for example, in lineages leading to the octopus or the honeybee."

The latest research indicates that of the five animal phyla, the highest classification in our evolutionary neighborhood, four contain worms.

But none are anatomically simpler than "acoels," which have no brains or centralized nervous systems. Less than a few millimeters in size, acoels are little more than tiny bags of cells that breathe through their skin and digest food by surrounding it.

Comparing extensive genome-wide data, mitochondrial genes and tiny signaling nucleic acids called microRNAs, the researchers hailing from six countries determined a strong possibility that acoels and their kin are "sisters" to another peculiar type of marine worm from northern seas, called Xenoturbella.

From there, like playing "Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon," the branches continue to humans.

"If you looked at one of these creatures you would say, 'what is all of this excitement about a worm?'" said Richard G. Northcutt, a professor of neurosciences at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, who was not involved in the study. "These are tiny animals that have almost no anatomy, which presents very little for scientists to compare them with. But through genetics, if the analysis is correct — and time will tell if it is — the study has taken a very bothersome group that scientists are not sure what to do with and says it is related to vertebrates, ourselves and echinoderms (such as starfish).

"The significance of the research is it gives us a better understanding of how animals are related and, by inference, a better understanding of the history of the animals leading to humans," Northcutt said.

Scientists used high-throughput computational tools to reconstruct deep evolutionary relationships, apparently confirming suspicions that three lineages of marine worms and vertebrates are part of a common evolutionary line called "deuterostomes," which share a common ancestor.

"The early evolution of lineages leading to vertebrates, sea stars and acorn worms is much more complex than most people expect because it involves not just gene gain, but enormous gene loss," said Moroz, who is affiliated with the Whitney Laboratory for Marine Bioscience and UF's McKnight Brain Institute. "An alternative, yet unlikely, scenario would be that our common ancestor had a central nervous system, and then just lost it, still remaining a free living organism.

Understanding the complex cellular rearrangements and the origin of animal innovations, such as the brain, is critically important for understanding human development and disease, Moroz said.

"We need to be able to interpret molecular events in the medical field," he said. "Is what's happening in different lineages of neuronal and stem cells, for example, completely new, or is it reflecting something that is in the arrays of ancestral tool kits preserved over more than 550 million years of our evolutionary history? Working with models of human disease, you really need to be sure."

###Scientists on the research team include Herve Philippe of the University of Montreal, Henner Brinkmann and Richard R. Copley of the Wellcome Trust Center for Human Genetics in Oxford, Hiroaki Nakano of the University of Tsukuba in Japan, Albert J. Poustka of the Max-Planck Institute in Berlin, Andreas Wallberg of Uppsala University in Sweden, Kevin J. Peterson of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire and Maximilian J. Telford of University College London.

Revisited human-worm relationships shed light on brain evolution

2011-02-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A race against time to find Apollo 14's lost voyagers

2011-02-10

In communities all across the US, travelers that went to the moon and back with the Apollo 14 mission are living out their quiet lives. The voyagers in question are not astronauts. They're "moon trees."

The seeds that later became moon trees orbited the moon 34 times in the Apollo 14 command module. In this classic Apollo 14 image, taken just before the lunar module landed at Fra Mauro, Earth peeks over the edge of the moon.

In communities all across the U.S., travelers that went to the moon and back with the Apollo 14 mission are living out their quiet lives. ...

Putting trees on farms fundamental to future agricultural development

2011-02-10

Nairobi, Kenya (9 February 2011) Trees growing on farms will be essential to future development. As the number of trees in forests is declining every year, the number of trees on farms is increasing. Marking the launch of the International Year of Forest by the United Nations Forum on Forests (UNFF9) in New York on 29 January, Dennis Garrity, the Director General of the World Agroforestry Centre, highlighted the importance of mixing trees with agriculture, the practice known as agroforestry.

"Over a billion hectares of agricultural land, almost half of the world's farmland, ...

New research helps explain how progesterone prevents preterm birth

2011-02-10

SAN FRANCISCO, FEB. 10, 2011 -- Research presented today at the 31st Annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) ― The Pregnancy Meeting™ has found that three proteins known as XIAP, BID, and Bcl-2 are responsible in part for the success of progesterone treatments in the prevention of preterm labor. They may also play an important role in triggering normal labor.

The proteins prevent preterm birth by hindering apoptosis – the normal, orderly death of cells -- in the fetal membranes. Stronger, thicker fetal membranes are less likely to rupture ...

Use of 17-hydroxyprogesterone doesn't reduce rate of preterm delivery or complications in twins

2011-02-10

SAN FRANCISCO (February 10, 2011) — In a study to be presented today at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine's (SMFM) annual meeting, The Pregnancy Meeting ™, in San Francisco, researchers will present findings that show that the use of the hormone 17-Hydroxyprogesterone does not reduce the rate of preterm delivery or neonatal complications in twins.

The hormone 17-Hydroxyprogesterone is sometimes used to reduce the risk of preterm labor. In 2008, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine issued an opinion ...

Study finds that folate does not offer protection against preterm delivery

2011-02-10

SAN FRANCISCO (February 10, 2011) — In a study to be presented today at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine's (SMFM) annual meeting, The Pregnancy Meeting ™, in San Francisco, researchers will present findings that show that folate intake before and during pregnancy does not protect Norwegian women against spontaneous preterm delivery.

"Sufficient folate intake has been studied as a possible protecting factor against spontaneous preterm delivery with conflicting results," said Verena Senpiel, M.D., one of the study's authors. "Preterm delivery is the major cause ...

Study finds magnesium sulfate may offer protection from cerebral palsy

2011-02-10

SAN FRANCISCO (February 10, 2011) — In a study to be presented today at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine's (SMFM) annual meeting, The Pregnancy Meeting ™, in San Francisco, researchers will present findings that showed that in rats, the use of magnesium sulfate (Mg) significantly reduced the neonatal brain injury associated with maternal inflammation or maternal infection.

Magnesium sulfate is sometimes used during preterm labor to reduce the risk of neonatal brain injury. In 2010 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal ...

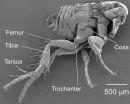

44-year-old mystery of how fleas jump resolved

2011-02-10

If you thought that we know everything about how the flea jumps, think again. In 1967, Henry Bennet-Clark discovered that fleas store the energy needed to catapult themselves into the air in an elastic pad made of resilin. However, in the intervening years debate raged about exactly how fleas harness this explosive energy. Bennet-Clark and Miriam Rothschild came up with competing hypotheses, but neither had access to the high speed recording equipment that could resolve the problem. Turn the clock forward to Malcolm Burrows' Cambridge lab in 2010. 'We were always very puzzled ...

New research helps explain how progesterone preventspreterm birth

2011-02-10

SAN FRANCISCO, FEB. 10, 2011 -- Research presented today at the 31st Annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) -- The Pregnancy Meeting™ has found that three proteins known as XIAP, BID, and Bcl-2 are responsible in part for the success of progesterone treatments in the prevention of preterm labor. They may also play an important role in triggering normal labor.

The proteins prevent preterm birth by hindering apoptosis – the normal, orderly death of cells -- in the fetal membranes. Stronger, thicker fetal membranes are less likely to rupture ...

Study finds women used 30 percent less analgesia during labor when self-administered

2011-02-10

SAN FRANCISCO (February 10, 2011) — In a study to be presented today at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine's (SMFM) annual meeting, The Pregnancy Meeting ™, in San Francisco, researchers will present findings that show that when women administer their own patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) instead of getting a continuous epidural infusion (CEI) they used less analgesic, but reported similar levels of satisfaction.

Women often receive a continuous epidural infusion of analgesic during labor. This can lead to prolonged labor and an increase in assisted vaginal ...

When first-time mothers are induced, breaking the amniotic membrane shortens delivery time

2011-02-10

SAN FRANCISCO (February 10, 2011) — In a study to be presented today at the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine's (SMFM) annual meeting, The Pregnancy Meeting ™, in San Francisco, researchers will present findings that show that by performing an amniotomy on first time mothers in situations when labor has to be induced, that delivery time can be shortened by more than 10 percent.

There are many reasons that labor may need to be induced after a woman's due date. Today's study looked at whether or not performing an amniotomy early on in the labor process would shorten ...