(Press-News.org) It has been long known that stress plays a part not just in the graying of hair but in hair loss as well. Over the years, numerous hair-restoration remedies have emerged, ranging from hucksters' "miracle solvents" to legitimate medications such as minoxidil. But even the best of these have shown limited effectiveness.

Now, a team led by researchers from UCLA and the Veterans Administration that was investigating how stress affects gastrointestinal function may have found a chemical compound that induces hair growth by blocking a stress-related hormone associated with hair loss — entirely by accident.

The serendipitous discovery is described in an article published in the online journal PLoS One.

"Our findings show that a short-duration treatment with this compound causes an astounding long-term hair regrowth in chronically stressed mutant mice," said Million Mulugeta, an adjunct professor of medicine in the division of digestive diseases at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and a corresponding author of the research. "This could open new venues to treat hair loss in humans through the modulation of the stress hormone receptors, particularly hair loss related to chronic stress and aging."

The research team, which was originally studying brain–gut interactions, included Mulugeta, Lixin Wang, Noah Craft and Yvette Taché from UCLA; Jean Rivier and Catherine Rivier from the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, Calif.; and Mary Stenzel-Poore from the Oregon Health and Sciences University.

For their experiments, the researchers had been using mice that were genetically altered to overproduce a stress hormone called corticotrophin-releasing factor, or CRF. As these mice age, they lose hair and eventually become bald on their backs, making them visually distinct from their unaltered counterparts.

The Salk Institute researchers had developed the chemical compound, a peptide called astressin-B, and described its ability to block the action of CRF. Stenzel-Poore had created an animal model of chronic stress by altering the mice to overproduce CRF.

UCLA and VA researchers injected the astressin-B into the bald mice to observe how its CRF-blocking ability affected gastrointestinal tract function. The initial single injection had no effect, so the investigators continued the injections over five days to give the peptide a better chance of blocking the CRF receptors. They measured the inhibitory effects of this regimen on the stress-induced response in the colons of the mice and placed the animals back in their cages with their hairy counterparts.

About three months later, the investigators returned to these mice to conduct further gastrointestinal studies and found they couldn't distinguish them from their unaltered brethren. They had regrown hair on their previously bald backs.

"When we analyzed the identification number of the mice that had grown hair we found that, indeed, the astressin-B peptide was responsible for the remarkable hair growth in the bald mice," Mulugeta said. "Subsequent studies confirmed this unequivocally."

Of particular interest was the short duration of the treatments: Just one shot per day for five consecutive days maintained the effects for up to four months.

"This is a comparatively long time, considering that mice's life span is less than two years," Mulugeta said.

So far, this effect has been seen only in mice. Whether it also happens in humans remains to be seen, said the researchers, who also treated the bald mice with minoxidil alone, which resulted in mild hair growth, as it does in humans. This suggests that astressin-B could also translate for use in human hair growth. In fact, it is known that the stress-hormone CRF, its receptors and other peptides that modulate these receptors are found in human skin.

INFORMATION:

The finding is an offshoot of a study funded by the National Institutes of Health.

UCLA and the Salk Institute have applied for a patent on the use of the astressin-B peptide for hair growth.

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies is one of the world's preeminent basic research institutions, where internationally renowned faculty probe fundamental life science questions in a unique, collaborative and creative environment. Focused both on discovery and on mentoring future generations of researchers, Salk scientists make groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of cancer, aging, Alzheimer's, diabetes and infectious diseases by studying neuroscience, genetics, cell and plant biology, and related disciplines. Faculty achievements have been recognized with numerous honors, including Nobel Prizes and memberships in the National Academy of Sciences. Founded in 1960 by polio vaccine

pioneer Jonas Salk, the institute is an independent nonprofit organization and architectural landmark.

The David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA ranks among the nation's elite medical schools, producing doctors and researchers whose contributions have led to major breakthroughs in health care. With more than 2,000 full-time faculty members, nearly 1,300 residents, more than 750 medical students and almost 400 Ph.D. candidates, the medical school is ranked seventh in the country in research funding from the National Institutes of Health and third in the United States in research dollars from all sources.

For more news, visit the UCLA Newsroom and follow us on Twitter.

Regrowing hair: UCLA-VA researchers may have accidentally discovered a solution

2011-02-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

1 group of enzymes could have a positive impact on health, from cholesterol to osteoporosis

2011-02-17

Montreal, February 16, 2011 – Recent studies conducted at the Institut de recherches cliniques de Montréal (IRCM) on a group of PCSK enzymes could have a positive impact on health, from cholesterol to osteoporosis. A team led by Dr. Nabil G. Seidah, Director of the Biochemical Neuroendocrinology research unit, has published six articles in prestigious scientific journals over the past four months, all shedding light on novel functions of certain PCSK enzymes.

PCSK enzymes belong to the proprotein convertase family, responsible for the conversion of an inactive protein ...

Neurologists develop software application to help identify subtle epileptic lesions

2011-02-17

Researchers from the Department of Neurology at NYU Langone Medical Center identified potential benefits of a new computer application that automatically detects subtle brain lesions in MRI scans in patients with epilepsy. In a study published in the February 2011 issue of PLoS ONE, the authors discuss the software's potential to assist radiologists in better identifying and locating visually undetectable, operable lesions.

"Our method automatically identified abnormal areas in MRI scans in 92 percent of the patients sampled, which were previously identified by expert ...

Increasing brain enzyme may slow Alzheimer's disease progression

2011-02-17

LOS ANGELES – Increasing puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase, the most abundant brain peptidase in mammals, slowed the damaging accumulation of tau proteins that are toxic to nerve cells and eventually lead to the neurofibrillary tangles, a major pathological hallmark of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia, according to a study published online in the journal, Human Molecular Genetics.

Researchers found they could safely increase the puromycin-sensitive aminopeptidase, PSA/NPEPPS, by two to three times the usual amount in animal models, and it removed the ...

Hip, thigh implants can raise bone fracture risk in children

2011-02-17

Children with hip and thigh implants designed to help heal a broken bone or correct other bone conditions are at risk for subsequent fractures of the very bones that the implants were intended to treat, according to new research from Johns Hopkins Children's Center.

Findings of the Johns Hopkins study, based on an analysis of more than 7,500 pediatric bone implants performed at Hopkins over 15 years, will be presented Feb. 16 at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

Although the absolute risk among the patients was relatively small — nine ...

Erg gene key to blood stem cell 'self-renewal'

2011-02-17

Scientists from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute have begun to unravel how blood stem cells regenerate themselves, identifying a key gene required for the process.

The discovery that the Erg gene is vitally important to blood stem cells' unique ability to self-renew could give scientists new opportunities to use blood stem cells for tissue repair, transplantation and other therapeutic applications.

Professor Doug Hilton, Dr Samir Taoudi and colleagues from the institute's Molecular Medicine and Cancer and Haematology divisions led the study. Dr Taoudi said the research ...

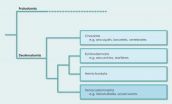

Xenacoelomorpha -- a new phylum in the animal kingdom

2011-02-17

An international team of scientists including Albert Poustka from the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin has discovered that Xenoturbellida and the acoelomorph worms, both simple marine worms, are more closely related to complex organisms like humans and sea urchins than was previously assumed. As a result they have made a major revision to the phylogenetic history of animals. Up to now, the acoelomate worms were viewed as the crucial link between simple animals like sponges and jellyfish and more complex organisms. It has now emerged that these animals ...

Tau-induced memory loss in Alzheimer's mice is reversible

2011-02-17

VIDEO:

To test their capacity to learn, the mice are trained to find an underwater platform which is not visible to them from the edge of a water basin. The swimming...

Click here for more information.

Amyloid-beta and tau protein deposits in the brain are characteristic features of Alzheimer disease. The effect on the hippocampus, the area of the brain that plays a central role in learning and memory, is particularly severe. However, it appears that the toxic effect of tau ...

Insects hold atomic clues about the type of habitats in which they live

2011-02-17

Scientists have discovered that insects contain atomic clues as to the habitats in which they are most able to survive. The research has important implications for predicting the effects of climate change on the insects, which make up three-quarters of the animal kingdom.

Applying a method previously only used to examine the possible effects of climate change on plants, scientists from the University of Cambridge can now determine the climatic tolerances of individual insects. Their research was published today, 16 February, in the scientific journal Biology Letters.

Because ...

Researchers link gene mutations to Ebstein's anomaly

2011-02-17

Ebstein's anomaly is a rare congenital valvular heart disease. Now, in patients with this disease, researchers of the Academic Medical Center Amsterdam in the Netherlands, the University of Newcastle, UK and the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC) Berlin-Buch have identified mutations in a gene which plays an important role in the structure of the heart. The researchers hope that these findings will lead to faster diagnosis and novel, more specifically targeted treatment methods (Circulation Cardiovascular Genetics, DOI: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.957985)*.

Ebstein's ...

Build your online networks using social annotations

2011-02-17

Researchers at Toshiba are working on a way of finding clusters of like-minded bloggers and others online using "social annotations". Social annotations are the tags and keywords, the comments and feedback that users, both content creators and others associate with their content. Their three-step approach could help you home in on people in a particular area of expertise much more efficiently and reliably than simply following search engine results. The same tools might also be used in targeted marketing.

Users of photo gallery sites, such as Flickr (http://www.flickr.com/) ...