(Press-News.org) University of California, Berkeley, chemists have engineered bacteria to churn out a gasoline-like biofuel at about 10 times the rate of competing microbes, a breakthrough that could soon provide an affordable and "green" transportation fuel.

The development is reported online this week in advance of publication in the journal Nature Chemical Biology by Michelle C. Y. Chang, assistant professor of chemistry at UC Berkeley, graduate student Brooks B. Bond-Watts and recent UC Berkeley graduate Robert J. Bellerose.

Various species of the Clostridium bacteria naturally produce a chemical called n-butanol (normal butanol) that has been proposed as a substitute for diesel oil and gasoline. While most researchers, including a few biofuel companies, have genetically altered Clostridium to boost its ability to produce n-butanol, others have plucked enzymes from the bacteria and inserted them into other microbes, such as yeast, to turn them into n-butanol factories. Yeast and E. coli, one of the main bacteria in the human gut, are considered to be easier to grow on an industrial scale.

While these techniques have produced promising genetically altered E. coli bacteria and yeast, n-butanol production has been limited to little more than half a gram per liter, far below the amounts needed for affordable production.

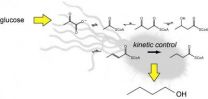

Chang and her colleagues stuck the same enzyme pathway into E. coli, but replaced two of the five enzymes with look-alikes from other organisms that avoided one of the problems other researchers have had: n-butanol being converted back into its chemical precursors by the same enzymes that produce it.

The new genetically altered E. coli produced nearly five grams of n-buranol per liter, about the same as the native Clostridium and one-third the production of the best genetically altered Clostridium, but about 10 times better than current industrial microbe systems.

"We are in a host that is easier to work with, and we have a chance to make it even better," Chang said. "We are reaching yields where, if we could make two to three times more, we could probably start to think about designing an industrial process around it."

"We were excited to break through the multi-gram barrier, which was challenging," she added.

Among the reasons for engineering microbes to make fuels is to avoid the toxic byproducts of conventional fossil fuel refining, and, ultimately, to replace fossil fuels with more environmentally friendly biofuels produced from plants. If microbes can be engineered to turn nearly every carbon atom they eat into recoverable fuel, they could help the world achieve a more carbon-neutral transportation fuel that would reduce the pollution now contributing to global climate change. Chang is a member of UC Berkeley's year-old Center for Green Chemistry.

The basic steps evolved by Clostridium to make butanol involve five enzymes that convert a common molecule, acetyl-CoA, into n-butanol. Other researchers who have engineered yeast or E. coli to produce n-butanol have taken the entire enzyme pathway and transplanted it into these microbes. However, n-butanol is not produced rapidly in these systems because the native enzymes can work in reverse to convert butanol back into its starting precursors.

Chang avoided this problem by searching for organisms that have similar enzymes, but that work so slowly in reverse that little n-butanol is lost through a backward reaction.

"Depending on the specific way an enzyme catalyzes a reaction, you can force it in the forward direction by reducing the speed at which the back reaction occurs," she said. "If the back reaction is slow enough, then the transformation becomes effectively irreversible, allowing us to accumulate more of the final product."

Chang found two new enzyme versions in published sequences of microbial genomes, and based on her understanding of the enzyme pathway, substituted the new versions at critical points that would not interfere with the hundreds of other chemical reactions going on in a living E. coli cell. In all, she installed genes from three separate organisms – Clostridium acetobutylicum, Treponema denticola and Ralstonia eutrophus -- into the E. coli.

Chang is optimistic that by improving enzyme activity at a few other bottlenecks in the n-butanol synthesis pathway, and by optimizing the host microbe for production of n-butanol, she can boost production two to three times, enough to justify considering scaling up to an industrial process. She also is at work adapting the new synthetic pathway to work in yeast, a workhorse for industrial production of many chemicals and pharmaceuticals.

INFORMATION:

The work was supported by UC Berkeley, the Camille and Henry Dreyfus Foundation, the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation and the Dow Sustainable Products and Solutions Program.

Turning bacteria into butanol biofuel factories

Transplanted enzyme pathway makes E. coli churn out n-butanol

2011-03-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Distractions Are Dangerous for Everyone on the Road

2011-03-03

The dangers of distracted driving are well established at this point. When drivers choose not to devote their full attention to the road, whether because they are sending text message or fiddling with the radio, the likelihood of car accidents increases.

However, drivers are not the only people who can cause car accidents while distracted. When pedestrians and cyclists are not paying proper attention while crossing the streets, they can pose a risk to themselves and others. According to 2009 statistics from the Illinois Department of Transportation, more than 5,300 car ...

New hope for lowering cholesterol

2011-03-03

A promising new way to inhibit cholesterol production in the body has been discovered, one that may yield treatments as effective as existing medications but with fewer side-effects.

In a new study published in the journal Cell Metabolism, a team of researchers from the UNSW School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences - led by Associate Professor Andrew Brown – report that an enzyme - squalene mono-oxygenase (SM) - plays a previously unrecognised role as a key checkpoint in cholesterol production. The team included doctoral students Saloni Gill and Julian Stevenson, ...

Type 2 diabetes linked to single gene mutation in 1 in 10 patients

2011-03-03

A multinational study has identified a key gene mutation responsible for type 2 diabetes in nearly 10 percent of patients of white European ancestry.

The study, which originated in Italy and was validated at UCSF, found that defects in the HMGA1 gene led to a major drop in the body's ability to make insulin receptors – the cell's sensor through which insulin tells the cell to absorb sugar. This drop in insulin receptors leads to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, according to the paper.

Findings appear in the March 2 issue of the Journal of the American Medical ...

Metal-On-Metal Hip Replacements Pose Serious Risks

2011-03-03

Metal-on-metal artificial hips are producing complications and injuries not seen with their plastic or ceramic predecessors. Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has drawn attention to the problems of these specific prostheses.

Total hip replacement systems consist of a ball and socket just like an organic hip. When both the ball and cup are made of metal, in the course of normal movements, such as walking or running, the metal ball and metal cup slide against one another. If the design is imperfect, complications can arise. Excessive friction, excessive looseness, ...

Ibuprofen may lower risk of Parkinson's disease

2011-03-03

ST. PAUL, Minn. – New research suggests that ibuprofen may offer protection against developing Parkinson's disease, according to one of the largest studies to date investigating the possible benefits of the over-the-counter drug on the disease. The study is published in the March 2, 2011, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology.

Parkinson's disease is a brain disorder that causes tremors and difficulty with movement and walking. It affects about one million people in the United States.

"Our results show that ibuprofen may ...

To bring effective therapies to patients quicker, use the team approach

2011-03-03

The current clinical trial process in the United States is on shaky ground. In this era of personalized medicine, as diseases are increasingly defined by specific genetic and biologic markers and treatments are tailored accordingly, patient populations for new therapies grow smaller and smaller. Coupled with skyrocketing costs and expanding regulatory requirements, the completion of trials that are essential in bringing new and effective therapies to patients is no easy task.

Change is needed.

Today, in the New England Journal of Medicine, a group of renowned researchers ...

Illegal Immigration Levels Off in 2010, Fewer Living in Florida

2011-03-03

Immigration debates are often fueled more by rhetoric than by actual facts and figures. Fortunately, the non-partisan Pew Research Center (which does not take positions on policy issues) offers objective statistics on immigration in their annual survey of national and state trends in immigration, as published by the Pew Hispanic Center.

The national highlights from Pew's 2010 immigration report include:

- Unauthorized immigrants make up about 3.7 percent of the nation's population --approximately 11.2 million persons. That number is statistically unchanged from last ...

Scientists target aggressive prostate cancer

2011-03-03

ANN ARBOR, Mich. — Researchers at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center have identified a potential target to treat an aggressive type of prostate cancer. The target, a gene called SPINK1, could be to prostate cancer what HER2 has become for breast cancer.

Like HER2, SPINK1 occurs in only a small subset of prostate cancers – about 10 percent. But the gene is an ideal target for a monoclonal antibody, the same type of drug as Herceptin, which is aimed at HER2 and has dramatically improved treatment for this aggressive type of breast cancer.

"Since SPINK1 ...

Scientists show how men amp up their X chromosome

2011-03-03

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — What makes a man? His clothes? His car? His choice of scotch? The real answer, says Brown University biologist Erica Larschan, is the newly understood activity of a protein complex that, like a genetic power tool, gives enzymes on the X-chromosome an extra boost to increase gene expression. The process is described in the March 3, 2011, issue of the journal Nature.

Women have two X-chromosomes in their genomes while males have an X and a Y. Gender is defined by that difference, but for men to live, the genetic imbalance must be remedied. ...

North Carolina Child Sex Crime Conviction Has Harsh Consequences

2011-03-03

The recent sentencing of a 28-year-old Gaston County man for multiple sex offenses, including second-degree sex offense of a child and one count of indecent liberties with a child, reveals the severe consequences that a conviction or guilty plea can bring. Marcus Stephen Archer pleaded guilty to two of six counts and faces up to ten years in prison as well as lifetime registration as a sex offender. He will also be required to submit to satellite monitoring after his release from prison.

Archer admits not remembering the events due to heavy drug use during the time the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

U.S. medical care is improving, but cost and health differ depending on disease

AI challenges lithography and provides solutions

Can AI make society less selfish?

UC Irvine researchers expose critical security vulnerability in autonomous drones

Changes in smoking status and their associations with risk of Parkinson’s, death

In football players with repeated head impacts, inflammation related to brain changes

Being an early bird, getting more physical activity linked to lower risk of ALS

The Lancet: Single daily pill shows promise as replacement for complex, multi-tablet HIV treatment regimens

Single daily pill shows promise as replacement for complex, multi-tablet HIV treatment regimens

Black Americans face increasingly higher risk of gun homicide death than White Americans

[Press-News.org] Turning bacteria into butanol biofuel factoriesTransplanted enzyme pathway makes E. coli churn out n-butanol