(Press-News.org) A team of neuroscientists at the University of Leicester, UK, in collaboration with researchers from Poland and Japan, has announced a breakthrough in the understanding of the 'brain chemistry' that triggers our response to highly stressful and traumatic events.

The discovery of a critical and previously unknown pathway in the brain that is linked to our response to stress is announced today in the journal Nature. The advance offers new hope for targeted treatment, or even prevention, of stress-related psychiatric disorders.

About 20% of the population experience some form of anxiety disorder at least once in their lives. The cumulative lifetime prevalence of all stress-related disorders is difficult to estimate but is probably higher than 30%.

Dr Robert Pawlak, from the University of Leicester who led the UK team, said: "Stress-related disorders affect a large percentage of the population and generate an enormous personal, social and economic impact. It was previously known that certain individuals are more susceptible to detrimental effects of stress than others. Although the majority of us experience traumatic events, only some develop stress-associated psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety or posttraumatic stress disorder. The reasons for this were not clear."

Dr Pawlak added that a lack of correspondence between the commonness of exposure to psychological trauma and the development of pathological anxiety prompted the researchers to look for factors that may make some individuals more vulnerable to stress than others.

"We asked: What is the molecular basis of anxiety in response to noxious stimuli? How are stress-related environmental signals translated into proper behavioural responses? To investigate these problems we used a combination of genetic, molecular, electrophysiological and behavioural approaches. This resulted in the discovery of a critical, previously unknown pathway mediating anxiety in response to stress."

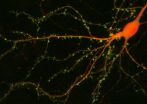

The study found that the emotional centre of the brain – the amygdala – reacts to stress by increasing production of a protein called neuropsin. This triggers a series of chemical events which in turn cause the amygdala to increase its activity. As a consequence, a gene is turned on that determines the stress response at a cellular level.

"We then examined behavioural consequences of the above series of cellular events caused by stress in the amygdala," said Dr Pawlak. "Studies in mice revealed that upon feeling stressed, they stayed away from zones in a maze where they felt unsafe. These were open and illuminated spaces they avoid when they are anxious."

"However when the proteins produced by the amygdala were blocked – either pharmacologically or by gene therapy – the mice did not exhibit the same traits. The behavioural consequences of stress were no longer present. We conclude that the activity of neuropsin and its partners may determine vulnerability to stress."

Neuropsin was previously discovered by Professor Sadao Shiosaka, a co-author of the paper. This research, for which the bioinformatics modelling was done by Professor Ryszard Przewlocki and his team, has for the first time characterized its mechanism of action in controlling anxiety in the amygdala.

The study took four years to complete, during which scientists from the Department of Cell Physiology and Pharmacology collaborated with colleagues from the Medical Research Council Toxicology Unit at the University of Leicester, the Department of Molecular Neuropharmacology, Polish Academy of Sciences in Krakow, Poland and Nara Institute of Science and Technology in Japan. The work was supported by the European Union, the Medical Research Council and Medisearch – the Leicestershire Medical Research Foundation. The first author, Benjamin Attwood, sponsored by Medisearch, took 3 years off from his medical studies curriculum to complete the necessary experiments. He commented: "It has been a thoroughly absorbing project to uncover how our experiences can change the way we behave. Hopefully this will lead to help for people that have to live with the damaging consequences of traumatic experiences."

Dr Pawlak added: "We are tremendously excited about these findings. We know that all members of the neuropsin pathway are present in the human brain. They may play a similar role in humans and further research will be necessary to examine the potential of intervention therapies for controlling stress-induced behaviours."

"Although research is now needed to translate our findings to the clinical situation, our discovery opens new possibilities for prevention and treatment of stress-related psychiatric disorders such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder."

INFORMATION:

Notes to Editors:

Dr Pawlak is available via e-mail. Please contact the University of Leicester press office: 0116 252 2415 email pressoffice@le.ac.uk

Details of the paper are as follows:

Neuropsin cleaves EphB2 in the amygdala to control anxiety

DOI: 10.1038/nature09938

Benjamin Attwood1, Julie-Myrtille Bourgognon1, Satyam Patel1, Mariusz Mucha1, Emanuele Schiavon1, Anna E. Skrzypiec1, Kenneth W. Young2, Sadao Shiosaka3, Michal Korostynski4, Marcin Piechota4, Ryszard Przewlocki4, Robert Pawlak1

1 Department of Cell Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Leicester, University Road, LE1 9HN, Leicester, UK

2 Medical Research Council Toxicology Unit, Lancaster Road, LE1 9HN, Leicester, UK

3 Division of Structural Cell Biology, Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Ikoma, Nara 630-0192, Japan

4 Department of Molecular Neuropharmacology, Institute of Pharmacology, 12 Smetna Street 31-343 Krakow, Poland

The following funding acknowledgements from the authors appear at the end of the paper:

This work was supported by Medical Research Council Project Grant (G0500231/73852), and a Marie Curie Excellence Grant (MEXT-CT-2006-042265 from European Commission) to Robert Pawlak, Medisearch Fellowship to Benjamin Attwood, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (Grants-in-Aid, # 20300128) and Japan Science and Technology Agency (CREST program) to Sadao Shiosaka, GENADDICT (LSHM-CT-005166 from the European Commission) to Ryszard Przewlocki and NN405 274137 from MNiSZW to Michal Korostynski.

ABOUT THE MRC:

For almost 100 years the Medical Research Council has improved the health of people in the UK and around the world by supporting the highest quality science. The MRC invests in world-class scientists. It has produced 29 Nobel Prize winners and sustains a flourishing environment for internationally recognised research. The MRC focuses on making an impact and provides the financial muscle and scientific expertise behind medical breakthroughs, including one of the first antibiotics penicillin, the structure of DNA and the lethal link between smoking and cancer. Today MRC funded scientists tackle research into the major health challenges of the 21st century. www.mrc.ac.uk.

About the EU Marie Curie award

A total of 50,000 researchers have been supported by the 'Marie Curie Actions' since 1996.

Support is available for researchers moving within Europe as well as to other parts of the world. Individual fellowships are also open to top researchers from outside the EU who want to carry out research in Europe.

Applications are evaluated by an independent panel of renowned European and international scientists. The evaluation is based on the scientific quality of the project and its likely impact on European competitiveness, as well as on the excellence of the host institute and the researcher.

Due to the high number of applicants, only the best projects are funded.

The EU will allocate more than €4.5 billion under the Marie Curie scheme between 2007 and 2013.

Medisearch – The Leicestershire Medical Research Foundation

Medisearch was set up in the 1970's as a charitable trust to support research within the Leicestershire Teaching Hospitals and The University of Leicester Medical School. The Trust maintains independence from the NHS and University, but is administered on a day to day basis by staff within the University of Leicester College of Medicine, Biological sciences and Psychology, on behalf of the Trustees.

By supporting and funding medical research and equipment across Leicestershire, Rutland and Northamptonshire, Medisearch aims to develop new treatments and promote a wider understanding of some of the most severe conditions. Through this research, the charity is bringing hope to future generations.

http://www.le.ac.uk/medisearch/

Neuroscientists discover new 'chemical pathway' in the brain for stress

Breakthrough study offers hope for targeted treatment of stress-related disorders

2011-04-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Be Bold and Bright This Summer With Boden

2011-04-21

Summer is as good reason as any to look fabulous, whether with a full-on bright look or with a bold accessory. Go for the coveted sun-kissed, vivid Summer look with a crayon box explosion of color from Boden. From colorful kaftans to shiny shoes, the new Summer collection will brighten your look, cheer up your wardrobe and put a smile on those around you.

Be beautiful and feel like a modern princess with Piazza Dress. The neck detail worthy of Cleopatra and the natural slubbiness of silk make it uniquely alluring. Top your dress off with the Printed Silk Scarf, its light-weight ...

Scientists prove new technology to control malaria-carrying mosquitoes

2011-04-21

Scientists at Imperial College London and the University of Washington, Seattle, have taken an important step towards developing control measures for mosquitoes that transmit malaria. In today's study, published in Nature, researchers have demonstrated how some genetic changes can be introduced into large laboratory mosquito populations over the span of a few generations by just a small number of modified mosquitoes. In the future this technological breakthrough could help to introduce a genetic change into a mosquito population and prevent it from transmitting the deadly ...

Immigrant screening misses majority of imported latent TB, finds study

2011-04-21

Current UK procedures to screen new immigrants for tuberculosis (TB) fail to detect more than 70 per cent of cases of latent infection, according to a new study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

TB is caused by a bacterial infection which is normally asymptomatic, but around one in 10 infections leads to active disease, which attacks the lungs and kills around half of people affected.

Today's research showed that better selection of which immigrants to screen with new blood tests can detect over 90 per cent of imported latent TB. These people can be given ...

Infants with persistent crying problems more likely to have behavior problems in childhood

2011-04-21

Infants who have problems with persistent crying, sleeping and/or feeding – known as regulatory problems – are far more likely to become children with significant behavioural problems, reveals research published ahead of print in the journal Archives of Disease in Childhood.

Around 20% of all infants show symptoms of excessive crying, sleeping difficulties and/or feeding problems in their first year of life and this can lead to disruption for families and costs for health services.

Previous research has suggested these regulatory problems can have an adverse effect ...

Long-term poverty but not family instability affects children's cognitive development

2011-04-21

Children from homes that experience persistent poverty are more likely to have their cognitive development affected than children in better off homes, reveals research published ahead of print in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.

Family instability, however, makes no additional difference to how a child's cognitive abilities have progressed by the age of five, after taking into account family poverty, family demographics (e.g. parental education and mother's age) and early child characteristics, UK researchers found.

There is much evidence of the ...

Adaptive trial designs could accelerate HIV vaccine development

2011-04-21

In the past 12 years, four large-scale efficacy trials of HIV vaccines have been conducted in various populations. Results from the most recent trial—the RV144 trial in Thailand, which found a 31 percent reduction in the rate of HIV acquisition among vaccinated heterosexual men and women—have given scientists reason for cautious optimism. Yet building on these findings could take years, given that traditional HIV vaccine clinical trials are lengthy, and that it is still not known which immune system responses a vaccine needs to trigger to protect an individual from HIV ...

Material that if scratched, you can quickly and easily fix yourself, with light not heat

2011-04-21

Imagine you're driving your own new car--or a rental car--and you need to park in a commercial garage. Maybe you're going to work, visiting a mall or attending an event at a sports stadium, and you're in a rush. Limited and small available spots and concrete pillars make parking a challenge. And it happens that day: you slightly misjudge a corner and you can hear the squeal as you scratch the side of your car--small scratches, but large anticipated repair costs.

Now imagine that that you can repair these unsightly scratches yourself--quickly, easily and inexpensively. ...

Repeated stress in pregnancy linked to children's behavior

2011-04-21

Research from Perth's Telethon Institute for Child Health Research has found a link between the number of stressful events experienced during pregnancy and increased risk of behavioural problems in children.

The study has just been published online in the latest edition of the top international journal Development and Psychopathology.

Common stressful events included financial and relationship problems, difficult pregnancy, job loss and issues with other children and major life stressors were events such as a death in the family.

Lead author, Registered Psychologist ...

Antimalarial trees in East Africa threatened with extinction

2011-04-21

NAIROBI (21 April 2011)— Research released in anticipation of World Malaria Day finds that plants in East Africa with promising antimalarial qualities—ones that have treated malaria symptoms in the region's communities for hundreds of years—are at risk of extinction. Scientists fear that these natural remedial qualities, and thus their potential to become a widespread treatment for malaria, could be lost forever.

A new book by researchers at the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF) and the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), Common Antimalarial Trees and Shrubs of ...

Singapore's first locally made satellite launched into space

2011-04-21

Singapore's first indigenous micro-satellite, X-SAT, lifted off on board India's Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle PSLV-C16 at 10.12am Indian Standard Time (12.42pm, Singapore time) on 20 April 2011.

The X-SAT, developed and built by Singapore's Nanyang Technological University (NTU), in collaboration with DSO National Laboratories, was launched from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre at Sriharikota in Andhra Pradesh, India.

The wholly made-in-Singapore satellite was one of the two "piggyback" mission satellites loaded on the PSLV-C16 rocket owned by the Indian Space Research ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Why conversation is more like a dance than an exchange of words

With Evo 2, AI can model and design the genetic code for all domains of life

Discovery of why only some early tumors survive could help catch and treat cancer at very earliest stages

Study reveals how gut bacteria and diet can reprogram fat to burn more energy

Mayo Clinic researchers link Parkinson's-related protein to faster Alzheimer's progression in women

Trends in metabolic and bariatric surgery use during the GLP-1 receptor agonist era

Loneliness, anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation in the all of us dataset

A decision-support system to personalize antidepressant treatment in major depressive disorder

Thunderstorms don’t just appear out of thin air - scientists' key finding to improve forecasting

Automated CT scan analysis could fast-track clinical assessments

New UNC Charlotte study reveals how just three molecules can launch gene-silencing condensates, organizing the epigenome and controlling stem cell differentiation

Oldest known bony fish fossils uncover early vertebrate evolution

High‑performance all‑solid‑state magnesium-air rechargeable battery enabled by metal-free nanoporous graphene

Improving data science education using interest‑matched examples and hands‑on data exercises

Sparkling water helps keep minds sharp during long esports sessions

Drone LiDAR surveys of abandoned roads reveal long-term debris supply driving debris-flow hazards

UGA Bioinformatics doctoral student selected for AIBS and SURA public policy fellowship

Gut microbiome connected with heart disease precursor

Nitrous oxide, a product of fertilizer use, may harm some soil bacteria

FAU lands $4.5M US Air Force T-1A Jayhawk flight simulator

SimTac: A physics-based simulator for vision-based tactile sensing with biomorphic structures

Preparing students to deal with ‘reality shock’ in the workplace

Researchers develop beating, 3D-printed heart model for surgical practice

Black soldier fly larvae show promise for safe organic waste removal

People with COPD commonly misuse medications

How periodontitis-linked bacteria accelerate osteoporosis-like bone loss through the gut

Understanding how cells take up and use isolated ‘powerhouses’ to restore energy function

Ten-point plan to deliver climate education unveiled by experts

Team led by UC San Diego researchers selected for prestigious global cancer prize

Study: Reported crop yield gains from breeding may be overstated

[Press-News.org] Neuroscientists discover new 'chemical pathway' in the brain for stressBreakthrough study offers hope for targeted treatment of stress-related disorders