(Press-News.org) The human eye long ago solved a problem common to both digital and film cameras: how to get good contrast in an image while also capturing faint detail.

Nearly 50 years ago, physiologists described the retina's tricks for improving contrast and sharpening edges, but new experiments by University of California, Berkeley, neurobiologists show how the eye achieves this without sacrificing shadow detail.

"One of the big success stories, and the first example of information processing by the nervous system, was the discovery that the nerve cells in the eye inhibit their neighbors, which allows the eye to accentuate edges," said Richard Kramer, UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology. "This is great if you only care about edges. But we also want to know about the insides of objects, especially in dim light."

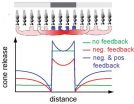

Kramer and former graduate student Skyler L. Jackman, now a post-doctoral fellow at Harvard University, discovered that while light-sensitive nerve cells in the retina inhibit dozens of their close neighbors, they also boost the response of the nearest one or two nerve cells.

That extra boost preserves the information in individual light detecting cells – the rods and cones – thereby retaining faint detail while accentuating edges, Kramer said. The rods and cones thus get both positive and negative feedback from their neighbors.

"By locally offsetting negative feedback, positive feedback boosts the photoreceptor signal while preserving contrast enhancement," he said.

Jackman, Kramer and their colleagues at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha report their findings today (Tuesday, May 3) in the journal PLoS Biology. Kramer also will report the findings today at the 2011 annual meeting of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology in Ft. Lauderdale, Fla.

From horseshoe crabs to humans

The fact that retinal cells inhibit their neighbors, an activity known as "lateral inhibition," was first observed in horseshoe crabs by physiologist H. Keffer Hartline. That discovery earned him a share of the 1967 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. This form of negative feedback was later shown to take place in the vertebrate eye, including the human eye, and has since been found in many sensory systems as a way, for example, to sharpen the discrimination of pitch or touch.

Lateral inhibition fails, however, to account for the eye's ability to detect faint detail near edges, including the fact that we can see small, faint spots that ought to be invisible if their detection is inhibited by encircling retinal cells.

Kramer noted that the details of lateral inhibition are still a mystery half a century after Hartline's discovery. Neurobiologists still debate whether the negative feedback involves an electrical signal, a chemical neurotransmitter, or protons that change the acidity around the cell.

"The field is at an impasse," Kramer said. "And we were surprised to find this fundamental new phenomenon, despite the fact that the anatomy of the retina has been known for more than 40 years."

The retina in vertebrates is lined with a sheet of photoreceptor cells: the cones for day vision and the rods for night vision. The lens of the eye focuses images onto this sheet, and like the pixels in a digital camera, each photoreceptor generates an electrical response proportional to the intensity of the light falling on it. The signal releases a chemical neurotransmitter (glutamate) that affects neurons downstream, ultimately reaching the brain.

Unlike the pixels of a digital camera, however, photoreceptors affect the photoreceptors around them through so-called horizontal cells, which underlie and touch as many as 100 individual photoreceptors. The horizontal cells integrate signals from all these photoreceptors and provide broad inhibitory feedback. This feedback is thought to underlie lateral inhibition, a process that sharpens our perception of contrast and color, Kramer said.

The new study shows that the horizontal cells also send positive feedback to the photoreceptors that have detected light, and perhaps to one or two neighboring photoreceptors.

"Positive feedback is local, whereas negative feedback extends laterally, enhancing contrast between center and surround," Kramer said.

Electrical vs. chemical signals

The two types of feedback work by different mechanisms, the researchers found. The horizontal cells undergo an electrical change when they receive neurotransmitter signals from the photoreceptors, and this voltage change quickly propagates throughout the cell, affecting dozens of nearby photoreceptors to lower their release of the glutamate neurotransmitter.

The positive feedback, however, involves chemical signaling. When a horizontal cell receives glutamate from a photoreceptor, calcium ions flow into the horizontal cell. These ions trigger the horizontal cell to "talk back" to the photoreceptor, Kramer said. Because calcium doesn't spread very far within the horizontal cell, the positive feedback signal stays local, affecting only one or two nearby photoreceptors.

The discovery of a new and unsuspected feedback mechanism in a very well-studied organ is probably related to how the eye is studied, Kramer said. Electrodes are typically stuck into the retina to both change the voltage in cells and record changes in voltage. Because the new signal is chemical, not electrical, it would have been easily missed.

Jackman and Kramer found the same positive feedback in the cones of a zebrafish, lizard, salamander, anole (whose retina contains only cones) and rabbit, proving that "this is not just some weird thing that happens in lizards; it seems to be true across all vertebrates and presumably humans," Kramer said.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the organization Research to Prevent Blindness.

Coauthors with Kramer and Jackman are Norbert Babai and Wallace B. Thoreson of the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center and James J. Chambers of the Department of Chemistry at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Why the eye is better than a camera at capturing contrast and faint detail simultaneously

Lateral inhibition sharpens edges, but positive feedback brings out detail

2011-05-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Simple exercise improves lung function in children with CF

2011-05-04

A small Johns Hopkins Children's Center study of children and teens with cystic fibrosis (CF) shows that simple exercise, individually tailored to each patient's preference and lifestyle, can help improve lung function and overall fitness.

Frequent lung infections, breathing problems and decreased lung function are the hallmark symptoms of CF, a genetic disorder marked by a disruption in the body's ability to transport chloride in and out of cells that leads to the buildup of thick mucus in the lungs and other organs.

Because rigidly structured high-intensity exercise ...

Robots learn to share, validating Hamilton's rule

2011-05-04

Using simple robots to simulate genetic evolution over hundreds of generations, Swiss scientists provide quantitative proof of kin selection and shed light on one of the most enduring puzzles in biology: Why do most social animals, including humans, go out of their way to help each other? In next week's issue of the online, open access journal PLoS Biology, EPFL robotics professor Dario Floreano teams up with University of Lausanne biologist Laurent Keller to weigh in on the oft-debated question of the evolution of altruism genes.

Altruism, the sacrificing of individual ...

Rate of coronary artery bypass graft surgeries decreases substantially

2011-05-04

Between 2001 and 2008, the annual rate of coronary artery bypass graft surgeries performed in the United States decreased by more than 30 percent, but rates of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI; procedures such as balloon angioplasty or stent placement used to open narrowed coronary arteries) did not change significantly, according to a study in the May 4 issue of JAMA.

"Coronary revascularization, comprising coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery and PCI, is among the most common major medical procedures provided by the U.S. health care system, with more ...

Unlocking the metabolic secrets of the microbiome

2011-05-04

The number of bacterial cells living in and on our bodies outnumbers our own cells ten to one. But the identity of all those bugs and just what exactly our relationship to all of them really is remains rather fuzzy. Now, researchers reporting in the May issue of Cell Metabolism, a Cell Press publication, have new evidence showing the metabolic impact of all those microbes in mice, and on their colons in particular.

"We point out one relatively general metabolite in the colon that has profound effects—it does a lot to keep things running smoothly," said Scott Bultman ...

Study evaluates relationship of urinary sodium with health outcomes

2011-05-04

In a study conducted to examine the health outcomes related to salt intake, as gauged by the amount of sodium excreted in the urine, lower sodium excretion was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular death, while higher sodium excretion did not correspond with increased risk of hypertension or cardiovascular disease complications, according to a study in the May 4 issue of JAMA.

"Extrapolations from observational studies and short-term intervention trials suggest that population-wide moderation of salt intake might reduce cardiovascular events," according ...

Popular diabetes drugs' cardiovascular side effects explained

2011-05-04

Drugs known as thiazolidinediones, or TZDs for short, are widely used in diabetes treatment, but they come with a downside. The drugs have effects on the kidneys that lead to fluid retention as the volume of plasma in the bloodstream expands.

"TZDs usually increase body weight by several kilograms," said George Seki of the University of Tokyo. "However, TZDs sometimes cause massive volume expansion, resulting in heart failure."

Now his team reports in the May issue of Cell Metabolism, a Cell Press publication, that those negative consequences arise in more than one ...

Many new drugs did not have comparative effectiveness information available at time of FDA approval

2011-05-04

Only about half of new drugs approved in the last decade had comparative effectiveness data available at the time of their approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and approximately two-thirds of new drugs had this information available when alternative treatment options existed, according to a study in the May 4 issue of JAMA.

In 2009, Congress allocated $1.1 billion to comparative effectiveness research. According to the Institute of Medicine, such research is defined as the "generation and synthesis of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of alternative ...

Structured exercise training associated with improved glycemic control for patients with diabetes

2011-05-04

Implementing structured exercise training, including aerobic, resistance or both, was associated with a greater reduction in hemoglobin A1c levels (a marker of glucose control) for patients with diabetes compared to patients in the control group, and longer weekly exercise duration was also associated with a greater decrease in these levels, according to results of an analysis of previous studies, published in the May 4 issue of JAMA.

"Exercise is a cornerstone of diabetes management, along with dietary and pharmacological interventions. Current guidelines recommend that ...

Turning 'bad' fat into 'good': A future treatment for obesity?

2011-05-04

By knocking down the expression of a protein in rat brains known to stimulate eating, Johns Hopkins researchers say they not only reduced the animals' calorie intake and weight, but also transformed their fat into a type that burns off more energy. The finding could lead to better obesity treatments for humans, the scientists report.

"If we could get the human body to turn 'bad fat' into 'good fat' that burns calories instead of storing them, we could add a serious new tool to tackle the obesity epidemic in the United States," says study leader Sheng Bi, M.D., an associate ...

Breast cancers found between mammograms more likely to be aggressive

2011-05-04

Breast cancers that are first detectable in the interval between screening mammograms are more likely to be aggressive, fast-growing tumors according to a study published online May 3rd in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Other studies have shown that cancers diagnosed between mammograms, known as interval cancers, tend to have a worse prognosis than those detected during routine screening. This study examined the difference between "true" interval cancers—those not detectable on the previous mammogram—and "missed" interval cancers—those not detected on ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

New ‘scimitar-crested’ Spinosaurus species discovered in the central Sahara

“Cyborg” pancreatic organoids can monitor the maturation of islet cells

Technique to extract concepts from AI models can help steer and monitor model outputs

Study clarifies the cancer genome in domestic cats

Crested Spinosaurus fossil was aquatic, but lived 1,000 kilometers from the Tethys Sea

MULTI-evolve: Rapid evolution of complex multi-mutant proteins

A new method to steer AI output uncovers vulnerabilities and potential improvements

Why some objects in space look like snowmen

Flickering glacial climate may have shaped early human evolution

First AHA/ACC acute pulmonary embolism guideline: prompt diagnosis and treatment are key

Could “cyborg” transplants replace pancreatic tissue damaged by diabetes?

Hearing a molecule’s solo performance

Justice after trauma? Race, red tape keep sexual assault victims from compensation

Columbia researchers awarded ARPA-H funding to speed diagnosis of lymphatic disorders

James R. Downing, MD, to step down as president and CEO of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in late 2026

A remote-controlled CAR-T for safer immunotherapy

UT College of Veterinary Medicine dean elected Fellow of the American Academy of Microbiology

AERA selects 34 exemplary scholars as 2026 Fellows

Similar kinases play distinct roles in the brain

New research takes first step toward advance warnings of space weather

Scientists unlock a massive new ‘color palette’ for biomedical research by synthesizing non-natural amino acids

Brain cells drive endurance gains after exercise

Same-day hospital discharge is safe in selected patients after TAVI

Why do people living at high altitudes have better glucose control? The answer was in plain sight

Red blood cells soak up sugar at high altitude, protecting against diabetes

A new electrolyte points to stronger, safer batteries

Environment: Atmospheric pollution directly linked to rocket re-entry

Targeted radiation therapy improves quality of life outcomes for patients with multiple brain metastases

Cardiovascular events in women with prior cervical high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

Transplantation and employment earnings in kidney transplant recipients

[Press-News.org] Why the eye is better than a camera at capturing contrast and faint detail simultaneouslyLateral inhibition sharpens edges, but positive feedback brings out detail