(Press-News.org) RICHLAND, Wash. – Today, farming often involves transporting crops long distances so consumers from Maine to California can enjoy Midwest corn, Northwest cherries and other produce when they are out of season locally. But it isn't just the fossil fuel needed to move food that contributes to agriculture's carbon footprint.

New research published in the journal Biogeosciences provides a detailed account of how carbon naturally flows into and out of crops themselves as they grow, are harvested and are then eaten far from where they're grown. The paper shows how regions that depend on others to grow their food end up releasing the carbon that comes with those crops into the atmosphere.

"Until recently, climate models have assumed that the carbon taken up by crops is put back into nature at the same place crops are grown," said the paper's lead author, environmental scientist Tristram West of the Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. "Our research provides a more accurate account of carbon in crops by considering the mobile nature of today's agriculture."

West works out of the Joint Global Change Research Institute, a partnership between PNNL and the University of Maryland. His co-authors are researchers at PNNL, Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Colorado State University.

Carbon, carbon everywhere

Carbon is the basis of life on Earth, including plants. During photosynthesis, plants take in carbon dioxide and convert it into carbon-based sugars needed to grow and live. When a plant dies, it decomposes and releases carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere. After eating plants, animals and humans release the plants' carbon as either carbon dioxide while breathing or as methane during digestion.

But the geography of this natural carbon cycle has shifted with the rise of commercial agriculture. Crops are harvested and shipped far away from where they're grown, instead of being consumed nearby. As a result, agriculturally active regions take in large amounts of carbon as crops grow. And regions with larger populations that consume those crops release the carbon.

The result is nearly net zero for carbon, with about the same amount of carbon being taken in as is released at the end. But the difference is where the carbon ends up. That geography matters for those who track every bit of carbon on Earth in an effort to estimate the potential impacts of greenhouse gases.

Digging into data

Agricultural carbon is currently tracked through two means: Towers placed in farm fields that are equipped with carbon dioxide sensors, and computer models that crunch data to generate estimates of carbon movement between land and the atmosphere. But neither method accounts for crops releasing carbon in areas other than where they were grown.

To more accurately reflect the carbon reality of today's agricultural crops, West and his co-authors combed through extensive data collected by various government agencies such as the Department of Agriculture, the U.S. Census Bureau and the Environmental Protection Agency.

Looking at 17 crops – including corn, soybeans, wheat and cotton – that make up 99 percent of total U.S. crop production, the researchers calculated the carbon content of harvested crops by county for each year from 2000 to 2008.

Next they used population numbers and data on human food intake to estimate, by age and gender, how much carbon from crops humans consume. On the flip side, the co-authors also calculated how much carbon humans release when they exhale, excrete and release flatulence. They did the same analysis on livestock and pets.

But not all food makes it to the dinner table. The researchers accounted for the crops that are lost due to spoilage or during processing, which ranges from 29 percent of collected dairy to as much as 57 percent of harvested vegetables. Beyond food, they determined the amount of carbon that goes into plant-based products such as fabric, cigarettes and biofuels. And they noted how much grain is stored for future use and the crops that are exported overseas.

National crop carbon budget

Combining all these calculations, the researchers developed a national crop carbon budget. Theoretically, all the carbon inputs should equal the carbon outputs from year to year. The researchers came very close, with no more than 6.1 percent of the initial carbon missing from their end calculations. This indicated that the team had accounted for the vast majority of the carbon from America's harvested crops.

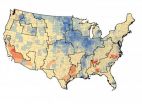

The team found overall that the crops take in – and later return – about 37 percent of the U.S.'s total annual carbon dioxide emissions, but that amount varies by region. Carbon sinks, or areas that take in more carbon than release it, were found in the agriculturally active regions of the Midwest, Great Plains and lands along the southern half of the Mississippi River. Regions with larger populations and less agriculture were found to be carbon sources, or areas that release more carbon than they take in. The calculations indicated the Northeast, Southeast and much of the Western U.S. and Gulf Coast were carbon sources. The remaining regions – the western interior and south-central U.S. – flip-flopped between being minor carbon sinks or sources, depending on the year.

Informing policy decisions

Next, West would like his team's methods applied to forestry, which also involves the movement of carbon-containing products from one locale to another. Comprehensive carbon calculations for agriculture and forestry could be used in connection with previous carbon estimates that were based on carbon dioxide sensor towers or carbon computer models.

"These calculations substantially improve what we know about the movement of carbon in agriculture," West said. "Reliable, comprehensive data like this can better inform policies aimed at managing carbon dioxide emissions."

This research was funded by NASA through the North American Carbon Program.

INFORMATION:

REFERENCE: West, T. O., Bandaru, V., Brandt, C. C., Schuh, A. E., and Ogle, S. M.: Regional uptake and release of crop carbon in the United States, Biogeosciences, 8, 2037-2046, doi: 10.5194/bg-8-2037-2011, 2011. Published online Aug. 3, 2011. http://www.biogeosciences.net/8/2037/2011/

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory is a Department of Energy Office of Science national laboratory where interdisciplinary teams advance science and technology and deliver solutions to America's most intractable problems in energy, the environment and national security. PNNL employs 4,900 staff, has an annual budget of nearly $1.1 billion, and has been managed by Ohio-based Battelle since the lab's inception in 1965. Follow PNNL on Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter.

The Joint Global Change Research Institute is a unique partnership formed in 2001 between the Department of Energy's Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and the University of Maryland. The PNNL staff associated with the center are world renowned for expertise in energy conservation and understanding of the interactions between climate, energy production and use, economic activity and the environment.

Carbon hitches a ride from field to market

Agriculture's mobile nature makes predicting regional greenhouse gas impacts more complex

2011-08-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

'Watermark ink' device identifies unknown liquids instantly

2011-08-04

Cambridge, Mass. - August 3, 2011 - Materials scientists and applied physicists collaborating at Harvard's School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have invented a new device that can instantly identify an unknown liquid.

The device, which fits in the palm of a hand and requires no power source, exploits the chemical and optical properties of precisely nanostructured materials to distinguish liquids by their surface tension.

The finding, published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society (JACS), offers a cheap, fast, and portable way to perform quality ...

UGA researchers use gold nanoparticles to diagnose flu in minutes

2011-08-04

Arriving at a rapid and accurate diagnosis is critical during flu outbreaks, but until now, physicians and public health officials have had to choose between a highly accurate yet time-consuming test or a rapid but error-prone test.

A new detection method developed at the University of Georgia and detailed in the August edition of the journal Analyst, however, offers the best of both worlds. By coating gold nanoparticles with antibodies that bind to specific strains of the flu virus and then measuring how the particles scatter laser light, the technology can detect influenza ...

GEN reports on nanotechology's impact on mass spectrometry

2011-08-04

New Rochelle, NY, August 3, 2011—A move toward smaller and smaller sample sizes is leading to a new generation of mass spectrometry instrumentation, reports Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News (GEN). From a specific application point of view, novel nanoflow separation methodologies are ramping up the speed and precision with which scientists are able to validate biomarkers, according to the August issue of GEN (www.genengnews.com/gen-articles/nanoliter-volumes-push-ms-to-new-lows/3741).

"Basing biomarker validation on more sophisticated mass spec tools could help ...

Researchers develop and test new molecule as a delivery vehicle to image and kill brain tumors

2011-08-04

RICHMOND, Va. (Aug. 3, 2011) – A single compound with dual function – the ability to deliver a diagnostic and therapeutic agent – may one day be used to enhance the diagnosis, imaging and treatment of brain tumors, according to findings from Virginia Commonwealth University and Virginia Tech.

Glioblastomas are the most common and aggressive brain tumor in humans, with a high rate of relapse. These tumor cells often extend beyond the well-defined tumor margins making it extremely difficult for clinicians and radiologists to visualize with current imaging techniques. Researchers ...

New study calls into question reliance on animal models in cardiovascular research

2011-08-04

Anyone who follows science has read enthusiastic stories about medical breakthroughs that include the standard disclaimer that the results were obtained in mice and might not carry over to humans.

Much later, there might be reports that a drug has been abandoned because clinical trials turned up unforeseen side effects or responses in humans. Given the delay, most readers probably don't connect the initial success and the eventual failure.

But Igor Efimov, PhD, a biomedical engineer at Washington University in St. Louis who studies the biophysical and physiological ...

Bellybutton microbiomes

2011-08-04

Public awareness about the role and interaction of microbes is essential for promoting human and environmental health, say scientists presenting research at the Ecological Society of America's (ESA) 96th Annual Meeting from August 7-12, 2011. Researchers shed light on the healthy microbes of the human body and other research on microbial and disease ecology to be presented at ESA's 2011 meeting in Austin, Texas.

Bellybutton microbiomes

Human skin is teeming with microbes—communities of bacteria, many of which are harmless, live alongside the more infamous microbes sometimes ...

Mold exposure during infancy increases asthma risk

2011-08-04

Infants who live in "moldy" homes are three times more likely to develop asthma by age 7—an age that children can be accurately diagnosed with the condition.

Study results are published in the August issue of Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, the scientific journal of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (ACAAI).

"Early life exposure to mold seems to play a critical role in childhood asthma development," says Tiina Reponen, PhD, lead study author and University of Cincinnati (UC) professor of environmental health. "Genetic factors are also ...

US physicians spend nearly 4 times more on health insurance costs than Canadian counterparts

2011-08-04

ITHACA, N.Y. — U.S. physicians spend nearly $61,000 more than their Canadian counterparts each year on administrative expenses related to health insurance, according to a new study by researchers at Cornell University and the University of Toronto.

The study, published in the August issue of the journal Health Affairs, found that per-physician costs in the U.S. averaged $82,975 annually, while Ontario-based physicians averaged $22,205 – primarily because Canada's single-payer health care system is simpler.

Canadian physicians follow a single set of rules, but U.S. doctors ...

Group Health establishes major initiative to prevent opioid abuse and overdose

2011-08-04

SEATTLE—Fatal overdoses involving prescribed opioids tripled in the United States between 1999 and 2006, climbing to almost 14,000 deaths annually—more than cocaine and heroin overdoses combined. Hospitalizations and emergency room visits related to prescription opioid pain medicines such as oxycodone (brand name Oxycontin) and hydrocodone (Vicodin) also increased dramatically in the same period.

Now a report in the August issue of Health Affairs describes a major initiative at Group Health to make opioid prescribing safer while improving care for patients with chronic ...

Compression stockings may reduce OSA in some patients

2011-08-04

Wearing compression stockings may be a simple low-tech way to improve obstructive sleep apnea in patients with chronic venous insufficiency, according to French researchers.

"We found that in patients with chronic venous insufficiency, compression stockings reduced daytime fluid accumulation in the legs, which in turn reduced the amount of fluid flowing into the neck at night, thereby reducing the number of apneas and hypopnea by more than a third," said Stefania Redolfi, MD, of the University of Brescia in Italy, who led the research.

CVI occurs when a patient's veins ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

The Lancet: First-ever in-utero stem cell therapy for fetal spina bifida repair is safe, study finds

Nanoplastics can interact with Salmonella to affect food safety, study shows

Eric Moore, M.D., elected to Mayo Clinic Board of Trustees

NYU named “research powerhouse” in new analysis

New polymer materials may offer breakthrough solution for hard-to-remove PFAS in water

Biochar can either curb or boost greenhouse gas emissions depending on soil conditions, new study finds

Nanobiochar emerges as a next generation solution for cleaner water, healthier soils, and resilient ecosystems

Study finds more parents saying ‘No’ to vitamin K, putting babies’ brains at risk

Scientists develop new gut health measure that tracks disease

Rice gene discovery could cut fertiliser use while protecting yields

Jumping ‘DNA parasites’ linked to early stages of tumour formation

Ultra-sensitive CAR T cells provide potential strategy to treat solid tumors

Early Neanderthal-Human interbreeding was strongly sex biased

North American bird declines are widespread and accelerating in agricultural hotspots

Researchers recommend strategies for improved genetic privacy legislation

How birds achieve sweet success

More sensitive cell therapy may be a HIT against solid cancers

Scientists map how aging reshapes cells across the entire mammalian body

Hotspots of accelerated bird decline linked to agricultural activity

How ancient attraction shaped the human genome

NJIT faculty named Senior Members of the National Academy of Inventors

App aids substance use recovery in vulnerable populations

College students nationwide received lifesaving education on sudden cardiac death

Oak Ridge National Laboratory launches the Next-Generation Data Centers Institute

Improved short-term sea level change predictions with better AI training

UAlbany researchers develop new laser technique to test mRNA-based therapeutics

New water-treatment system removes nitrogen, phosphorus from farm tile drainage

Major Canadian study finds strong link between cannabis, anxiety and depression

New discovery of younger Ediacaran biota

Lymphovenous bypass: Potential surgical treatment for Alzheimer's disease?

[Press-News.org] Carbon hitches a ride from field to marketAgriculture's mobile nature makes predicting regional greenhouse gas impacts more complex