(Press-News.org)

VIDEO:

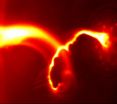

An argon plasma jet forms a rapidly growing corkscrew, known as a kink instability. This instability causes an even faster-developing behavior called a Rayleigh-Taylor instability, in which ripples grow and...

Click here for more information.

PASADENA, Calif.—January saw the biggest solar storm since 2005, generating some of the most dazzling northern lights in recent memory.

The source of that storm—and others like it—was the sun's magnetic field, described by invisible field lines that protrude from and loop back into the burning ball of gas. Sometimes these field lines break—snapping like a rubber band pulled too tight—and join with other nearby lines, releasing energy that can then launch bursts of plasma known as sol ar flares. Huge chunks of plasma from the sun's surface can zip toward Earth and damage orbiting satellites or bump them off their paths.

These chunks of plasma, called coronal mass ejections, can also snap Earth's magnetic field lines, causing charged particles to speed toward Earth's magnetic poles; this, in turn, sets off the shimmering light shows we know as the northern and southern lights.

Even though the process of field lines breaking and merging with other lines—called magnetic reconnection—has such significant effects, a detailed picture of what precisely is going on has long eluded scientists, says Paul Bellan, professor of applied physics in the Division of Engineering and Applied Science at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

Now, using high-speed cameras to look at jets of plasma in the lab, Bellan and graduate student Auna Moser have discovered a surprising phenomenon that provides clues to just how magnetic reconnection occurs. They describe their results in a paper published in the February 16 issue of the journal Nature.

"Trying to understand nature by using engineering techniques is indeed a hallmark of the Division of Engineering and Applied Science at Caltech," says Ares Rosakis, the Theodore von Kármán Professor of Aeronautics and professor of mechanical engineering and the chair of engineering and applied science.

In the experiments, Moser fired jets of hydrogen, nitrogen, and argon plasmas at speeds of about 10 to 50 kilometers per second across a distance of more than 20 centimeters in a vacuum. Plasma is a gas so hot that atoms are stripped of their electrons. As a throughway for speeding electrons, the jets act like electrical wires. The experiment requires 200 million watts of power to produce jets that are a scorching 20,000 degrees Kelvin and carry a current of 100,000 amps. To study the jets, Moser used cameras that can take a snapshot in less than a microsecond, or one millionth of a second.

As in all electrical currents, the flowing electrons in the plasma jet generate a magnetic field, which then exerts a force on the plasma. These electromagnetic interactions between the magnetic field and the plasma can cause the jet to writhe and form a rapidly expanding corkscrew. This behavior, called a kink instability, has been studied for nearly 60 years, Bellan says.

But when Moser looked closely at this behavior in her experimental plasma jets, she saw something entirely unexpected.

She found that—more often than not—the corkscrew shape that developed in her jets grew exponentially and extremely fast. The jets in the experiment formed 20-centimeter-long coils in just 20 to 25 microseconds. She also noticed tiny ripples that began appearing on the inner edge of the coil just before the jet broke—the moment when there was a magnetic reconnection.

In the beginning, Moser and Bellan say, they did not know what they were seeing—they just knew it was strange. "I thought it was a measurement error," Bellan says. "But it was way too reproducible. We were seeing it day in and day out. At first, I thought we would never figure it out."

But after months of additional experiments, they determined that the kink instability actually spawns a completely different kind of phenomenon, called a Rayleigh-Taylor instability. A Rayleigh-Taylor instability happens when a heavy fluid that sits on top of a light fluid tries to trade places with the light fluid. Ripples form and grow at the interface between the two, allowing the fluids to swap places.

What Moser and Bellan realized is that the kink instability creates conditions that give rise to a Rayleigh-Taylor instability. As the coiled plasma expands—due to the kink instability—it accelerates outward. Just like a passenger being pushed back into the seat of an accelerating car, the accelerated plasma is pushed down on the vacuum behind it. The plasma tries to swap places with the trailing vacuum by forming ripples that then expand—just like when gravity forces a heavy fluid to try to change places with a light fluid underneath. The Rayleigh-Taylor instability—as revealed by the ripples on the trailing side of the accelerating plasma—grows in about a microsecond.

"People have not observed anything like this before," Bellan says.

Although the Rayleigh-Taylor instability has been studied for more than 100 years, no one had considered the possibility that it could be caused by a kink instability, Bellan says. The two types of instabilities are so different that to see them so closely coupled was a shock. "Nobody ever thought there was a connection," he says.

What is notable is that the two instabilities occur at very different scales, the researchers say. While the coil created by the kink instability spans about 20 centimeters, the Rayleigh-Taylor instability is much smaller, making ripples just two centimeters long. Still, those smaller ripples rapidly erode the jet, forcing the electrons to flow faster and faster through a narrowing channel. "You're basically choking it off," Bellan explains. Soon, the jet breaks, causing a magnetic reconnection.

Magnetic reconnection on the sun often involves phenomena that span scales from a million meters to just a few meters. At the larger scales, the physics is relatively simple and straightforward. But at the smaller scales, the physics becomes more subtle and complex—and it is in this regime that magnetic reconnection takes place. Magnetic reconnection is also a key issue in developing thermonuclear fusion as a future energy source using plasmas in the laboratory. One of the key advances in this study, the researchers say, is being able to relate phenomena at large scales, such as the kink instability, to those at small scales, such as the Rayleigh-Taylor instability.

The researchers note that, although kink and Rayleigh-Taylor instabilities may not drive magnetic reconnection in all cases, this mechanism is a plausible explanation for at least some scenarios in nature and the lab.

INFORMATION:

The title of Moser and Bellan's Nature paper is "Magnetic reconnection from a multiscale instability cascade." This research was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Science Foundation, and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research.

Written by Marcus Woo

Plasmas torn apart

Caltech researchers make discovery that hints at origin of phenomena like solar flares

2012-02-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Tool assessing how community health centers deliver 'medical home' care may be flawed

2012-02-16

On the health front, the poor often have at least two things going against them: a lack of insurance and chronic illnesses, of which diabetes is among the most common.

The federal Affordable Care Act would expand the capacity of the nation's 8,000 community health centers to provide care for low-income, largely minority patients — from the current 20 million to about 40 million by 2015. The federal government is also trying to ensure that these community health centers deliver high-quality primary care, including diabetes care.

A crucial part of this is the implementation ...

Astronomers watch delayed broadcast of a rare celestial eruption

2012-02-16

Pasadena, CA— Eta Carinae, one of the most massive stars in our Milky Way galaxy, unexpectedly increased in brightness in the 19th century. For ten years in the mid-1800s it was the second-brightest star in the sky. (Now it is not even in the top 100.) The increase in luminosity was so great that it earned the rare title of Great Eruption. New research from a team including Carnegie's Jose Prieto, now at Princeton University, has used a "light echo" technique to demonstrate that this eruption was much different than previously thought. Their work is published Feb. 16 in ...

Contraceptive preferences among young Latinos related to sexual decision-making

2012-02-16

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Half of the young adult Latino men and women responding to a survey in rural Oregon acknowledge not using regular effective contraception – despite expressing a desire to avoid pregnancy, according to a new Oregon State University study.

Researchers say the low rate of contraception among sexually active 18- to 25-year-olds needs to be addressed – and not just among Latino populations. Research has shown many young adults from all backgrounds eschew contraception for many reasons including the mistaken belief that they or their partners cannot get pregnant.

"The ...

Complexities in caregiving at the end of life

2012-02-16

Faced with the inevitability of death, we all wish for good caregiving during the final stage of our lives. A new study from Karolinska Institutet and Umeå University shows that non-pharmacological caregiving at the end of life in specialized palliative care is not as basic as one might believe but is based on complex professional decisions that weave physical, psychosocial and existential dimensions into a functional whole. The researchers have found that particularly important aspects of palliative care are an aesthetically pleasing, safe and comfortable environment, ...

New miniature grasshopper-like insect is first member of its family from Belize

2012-02-16

Scientists at the University of Illinois, USA have discovered a new species of tiny, grasshopper-like insect in the tropical rainforests of the Toledo District in southern Belize. Dr Sam Heads and Dr Steve Taylor co-authored a paper, published in the open access journal ZooKeys, documenting the discovery and naming the new species Ripipteryx mopana. The name commemorates the Mopan people – a Mayan group, native to the region.

"Belize is famous for its biodiversity, although very little is known about the insect fauna of the southern part of the country. This is particularly ...

Research highlights urgent need to tackle low number of organ donors from BME communities

2012-02-16

There is an urgent need to increase the number of organ donors from black and minority ethnic (BME) groups in countries with a strong tradition of immigration, such as the UK, USA, Canada and the Netherlands, in order to tackle inequalities in access and waiting times.

That is the key finding of a research paper on ethnicity and transplants, published by the Journal of Renal Care in a free online supplement that includes 15 studies on different aspects of diabetes and kidney disease.

"BME groups are disproportionately affected by kidney problems for a number of ...

Green spaces reduce stress levels of jobless, study shows

2012-02-16

Stress levels of unemployed people are linked more to their surroundings than their age, gender, disposable income, and degree of deprivation, a study shows.

The presence of parks and woodland in economically deprived areas may help people cope better with job losses, post traumatic stress disorder, chronic fatigue and anxiety, researchers say.

They found that people's stress levels are directly related to the amount of green space in their area – the more green space, the less stressed a person is likely to be.

Researchers measured stress by taking saliva samples ...

Low-carbon technologies 'no quick-fix', say researchers

2012-02-16

A drastic switch to low carbon-emitting technologies, such as wind and hydroelectric power, may not yield a reduction in global warming until the latter part of this century, research published today suggests.

Furthermore, it states that technologies that offer only modest reductions in greenhouse gases, such as the use of natural gas and perhaps carbon capture and storage, cannot substantially reduce climate risk in the next 100 years.

The study, published today, Thursday 16 February, in IOP Publishing's journal Environmental Research Letters, claims that the rapid ...

Stretching helices help keep muscles together

2012-02-16

VIDEO:

When myomesin is pulled, as it is when muscles contract and extend, its helices (green) unfold. This strategy, discovered by scientists at EMBL Hamburg, enables the elastic part of the...

Click here for more information.

In this video, a protein called myomesin does its impression of Mr. Fantastic, the leader of the Fantastic Four of comic book fame, who performed incredible feats by stretching his body. Scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in ...

New molecule discovered in fight against allergy

2012-02-16

Scientists at The University of Nottingham have discovered a new molecule that could offer the hope of new treatments for people allergic to the house dust mite.

The team of immunologists led by Dr Amir Ghaem-Maghami and Professor Farouk Shakib in the University's School of Molecular Medical Sciences have identified the molecule DC-SIGN which appears to play a role in damping down the body's allergic response to the house dust mite .

The molecule can be found on the surface of the immune cells which play a key role in the recognition of a major allergen from house dust ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

[Press-News.org] Plasmas torn apartCaltech researchers make discovery that hints at origin of phenomena like solar flares