(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio - New research confirms an association between smoking and a reduced risk for a rare benign tumor near the brain, but the addition of smokeless tobacco to the analysis suggests nicotine is not the protective substance.

The study using Swedish data suggests that men who currently smoke are almost 60 percent less likely than people who have never smoked to develop this tumor, called an acoustic neuroma. But men in the study who used snuff, which produces roughly the same amount of nicotine in the blood as smoking, had no reduced risk of tumor development.

"We see this effect with current smokers but don't see it with current snuff users, so we think that maybe the protective effect has something to do with the combustion process or one of the other chemicals in cigarettes that are not in snuff," said Sadie Palmisano, a doctoral student in epidemiology at Ohio State University and lead author of the study. "We learned something from exclusion."

Acoustic neuroma is a tumor that grows on the vestibular cochlear nerve connecting the ear to the brain. It is not cancer, but it can cause nerve damage as well as symptoms that include vertigo, ringing in the ears and hearing loss. The only treatment for these slow-growing tumors is surgical removal or high-powered radiation that reduces their size. About one in 100,000 people per year develops these growths, which account for approximately 8 percent of all primary tumors inside the skull in the United States.

A few previous studies have found a similar link between smoking and lowered risk for development of these tumors, but did not take snuff use into account. Though the research is aimed at prevention of acoustic neuromas, the researchers emphasized that they do not endorse smoking as a way to avoid developing a tumor.

The findings suggested to the scientists that a lack of oxygen associated with smoking might help prevent the tumors by starving the cells whose overgrowth leads to the formation of an acoustic neuroma. These are called Schwann cells, and they produce the myelin coating on nerve cells in the peripheral nervous system outside the brain and spinal cord.

The research is published online and scheduled for future print publication in the American Journal of Epidemiology.

The scientists conducted a nationwide study of acoustic neuroma between 2002 and 2007, compiling data on Swedish patients between the ages of 20 and 69 years at the time of diagnosis with the tumors. These patients, as well as healthy Swedish control participants, also completed questionnaires about environmental exposures and lifestyle choices.

Palmisano and colleagues applied statistical analysis to these data to determine associations between smoking and snuff use and risk for acoustic neuroma. The analysis included data on 423 patients with tumors and 645 controls matched for age, sex and home location.

"We got practically all of the diagnosed cases in Sweden - there was an 84 percent participation rate. On top of that, a population-based registry served as the basis for the control sample. This made it incredibly representative of the population, and with the sample being this large, we make the case that the link between smoking and reduced risk for acoustic neuroma is there," Palmisano said.

The link was especially strong in men who were current smokers - a 59-percent reduction in risk for acoustic neuroma compared to people who had never smoked. In women current smokers, the association was smaller - a 30 percent reduced risk compared to never-smokers, with more statistical room for this link to be attributed to chance.

Current smokers were those who smoked at least one cigarette per day for six months or longer. For people who had smoked and then quit, including even longtime smokers, "we didn't find as much of an effect. It's like a puzzle," Palmisano said.

The researchers evaluated smokeless tobacco use among only men because too few women reported using snuff. The scientists found no difference in the risk for acoustic neuroma between current or past snuff users and people who had never used snuff.

These findings about snuff imply that nicotine is not providing the protection because habitual snuff users and smokers have similar levels of nicotine in their blood. By determining that snuff users reap no acoustic neuroma preventive benefits from the smokeless tobacco, the researchers determined that nicotine should probably be ruled out as a potentially protective compound in this context.

The Swedish and American forms of snuff differ substantially, so these findings do not translate to users of American smokeless tobacco, which is fermented and contains more chemicals than does Swedish snuff.

Many studies have also linked smoking with a reduced risk for Parkinson's disease, leading scientists to continue looking for clues about how tobacco can have this effect on nervous-system processes. Palmisano also will use the Swedish data to explore other potential causes of acoustic neuromas, including exposure to loud noises. The only known cause of the tumors is a genetic condition called neurofibromatosis. Two different sources of radiation also have been linked to increased risk for the tumors.

###This study was funded by the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research.

Palmisano conducted the research with Judith Schwartzbaum, associate professor of epidemiology at Ohio State, as well as Swedish co-authors Michaela Prochazka, David Peterson and Maria Feychting of the Karolinska Institutet; Tommy Bergenheim of Umeå University Hospital; Rut Florentzson of Sahlgrenska University Hospital; Henrik Harder of Linköping University Hospital; Tiit Mathiesen of Karolinska Hospital; Gunnar Nyberg of Uppsala University Hospital; and Peter Siesjö of Lund University Hospital.

Contact:

Sadie Palmisano, (614) 293-9046; sadie.palmisano@osumc.edu, or Judith Schwartzbaum, (614) 292-5152 or schwartzbaum.1@osu.edu (Schwartzbaum travels frequently. E-mail is the best way to initiate contact with her.)

Written by Emily Caldwell, (614) 292-8310; caldwell.151@osu.edu

Study suggests smoking, but not nicotine, reduces risk for rare tumor

2012-04-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Study finds 'Western diet' detrimental to fetal hippocampal tissue transplants

2012-04-24

Tampa, Fla. (April. 23, 2012) – Researchers interested in determining the direct effects of a high saturated fat and high cholesterol (HFHC) diet on implanted fetal hippocampal tissues have found that in middle-aged laboratory rats the HFHC diet elevated microglial activation and reduced neuronal development. While the resulting damage was due to an inflammatory response in the central nervous system, they found that the effects of the HFHC diet were alleviated by the interleukin (IL)-1 receptor antagonist IL-1Ra, leading them to conclude that IL-Ra has potential use in ...

Medical 'lightsabers': Laser scalpels get ultrafast, ultra-accurate, and ultra-compact makeover

2012-04-24

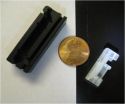

WASHINGTON, April 23—Whether surgeons slice with a traditional scalpel or cut away with a surgical laser, most medical operations end up removing some healthy tissue, along with the bad. This means that for delicate areas like the brain, throat, and digestive tract, physicians and patients have to balance the benefits of treatment against possible collateral damage.

To help shift this balance in the patient's favor, a team of researchers from the University of Texas at Austin has developed a small, flexible endoscopic medical device fitted with a femtosecond laser "scalpel" ...

Robots fighting wars could be blamed for mistakes on the battlefield

2012-04-24

As militaries develop autonomous robotic warriors to replace humans on the battlefield, new ethical questions emerge. If a robot in combat has a hardware malfunction or programming glitch that causes it to kill civilians, do we blame the robot, or the humans who created and deployed it?

Some argue that robots do not have free will and therefore cannot be held morally accountable for their actions. But University of Washington psychologists are finding that people don't have such a clear-cut view of humanoid robots.

The researchers' latest results show that humans apply ...

New South Asia network to tackle 'massive' climate adaptation challenge

2012-04-24

KATHMANDU, NEPAL (24 April 2012)—Today, recognizing the knowledge gap between the existing evidence of climate change and adaptation on the ground, researchers in Asia launched a novel learning platform to improve agricultural resilience to changing weather patterns, and to reduce emissions footprint.

The Climate Smart Agriculture Learning Platform for South Asia, established by the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), will improve communication between scientists, government officials, civil society and farmers on best "climate ...

Researchers study costs of 'dirty bomb' attack in L.A.

2012-04-24

A dirty bomb attack centered on downtown Los Angeles' financial district could severely impact the region's economy to the tune of nearly $16 billion, fueled primarily by psychological effects that could persist for a decade.

The study, published by a team of internationally recognized economists and decision scientists in the current issue of Risk Analysis, monetized the effects of fear and risk perception and incorporated them into a state-of-the-art macroeconomic model.

"We decided to study a terrorist attack on Los Angeles not to scare people, but to alert policymakers ...

A physician's guide for anti-vaccine parents

2012-04-24

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- In the limited time of an office visit, how can a primary care physician make the case to parents that their child should be vaccinated? During National Infant Immunization Week, a Mayo Clinic vaccine expert and a pediatrician offer suggestions for refuting three of the most common myths about child vaccine safety. Their article, The Clinician's Guide to the Anti-Vaccinationists' Galaxy, is published online this month in the journal Human Immunology.

"Thousands of children are at increased risk because of under-vaccination, and outbreaks of highly ...

Letting go can boost quality of life

2012-04-24

Montreal, April 23, 2012 — Most people go through life setting goals for themselves. But what happens when a life-altering experience makes those goals become unachievable or even unhealthy?

A new collaborative study published in Psycho-Oncology by Carsten Wrosch of Concordia University's Department of Psychology and Centre for Research in Human Development and Catherine Sabiston of McGill's Department of Kinesiology and Physical Education and the Health Behaviour and Emotion Lab found that breast cancer survivors who were able to let go of old goals and set new ones ...

IADR/AADR publish studies on severe early childhood caries – proposes new classification

2012-04-24

Alexandria, Va., USA – The International and American Associations for Dental Research have published two studies about dental caries in children. These articles, titled "Hypoplasia-Associated Severe Early Childhood Caries – A Proposed Definition" (lead author Page Caufield, New York University College of Dentistry) and "Deciduous Molar Hypomineralization and Molar Incisor Hypomineralization" (lead author M.E.C. Elfrink, Academic Centre for Dentistry, Amsterdam) discuss the definitions of dental caries susceptibility to the hypomineralization and hypoplasia.

The study ...

Towards an agroforestry policy in Indonesia

2012-04-24

INDONESIA (23 April 2012) — The importance of collaboration among all research partners in agroforestry was recently emphasised at a historic workshop to develop a national strategy on agroforestry research in Indonesia.

During the meeting, five key challenges facing agroforestry in Indonesia were also identified. The first challenge mentioned was the Government's partial approach to research, which translates into low adoption of research recommendations. Second, land tenure insecurity, particularly in State forest areas, leads to social conflict and degradation of ...

Immunosignaturing: An accurate, affordable and stable diagnostic

2012-04-24

Identifying diseases at an early, presymptomatic stage may offer the best chance for establishing proper treatment and improving patient outcomes. A new technique known as immunosignaturing harnesses the human immune system as an early warning sentry—one acutely sensitive to changes in the body that may be harbingers of illness.

Now, Brian Andrew Chase and Barten Legutki, under the guidance of Stephen Albert Johnston, director of the Center for Innovations in Medicine at Arizona State University's Biodesign Institute have shown that these immunosignatures are not only ...