(Press-News.org) Douglas McCauley and Paul DeSalles did not set out to discover one of the longest ecological interaction chains ever documented. But that's exactly what they and a team of researchers – all current or former Stanford students and faculty – did in a new study published in Scientific Reports.

Their findings shed light on how human disturbance of the natural world may lead to widespread, yet largely invisible, disruptions of ecological interaction chains. This, in turn, highlights the need to build non-traditional alliances – among marine biologists and foresters, for example – to address whole ecosystems across political boundaries.

This past fall, McCauley, a graduate student, and DeSalles, an undergraduate, were in remote Palmyra Atoll in the Pacific tracking manta rays' movements for a predator-prey interaction study. Swimming with the rays and charting their movements with acoustic tags, McCauley and DeSalles noticed the graceful creatures kept returning to certain islands' coastlines. Meanwhile, graduate student Hillary Young was studying palm tree cultivation's effect on native habitats nearby and wondering how the impact on bird communities would play out.

Palmyra is a unique spot on Earth where scientists can compare largely intact ecosystems within shouting distance of recently disturbed habitats. A riot of life – huge grey reef sharks, rays, snapper and barracuda – plies the clear waters while seabirds flock from thousands of miles away to roost in the verdant forests of this tropical idyll.

Over meals and sunset chats at the small research station, McCauley, DeSalles, Young and other scientists discussed their work and traded theories about their observations. "As the frequencies of these different conversations mixed together, the picture of what was actually happening out there took form in front of us," McCauley said.

Through analysis of nitrogen isotopes, animal tracking and field surveys, the researchers showed that replacing native trees with non-native palms led to about five times fewer roosting seabirds (they seemed to dislike palms' simple and easily wind-swayed canopies), which led to fewer bird droppings to fertilize the soil below, fewer nutrients washing into surrounding waters, smaller and fewer plankton in the water and fewer hungry manta rays cruising the coastline.

"This is an incredible cascade," said researcher Rodolfo Dirzo, a senior fellow with the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment. "As an ecologist, I am worried about the extinction of ecological processes."

Equally important is what the study suggests about these cascades going largely unseen. "Such connections do not leave any trace behind," said researcher Fiorenza Micheli, an associate professor of biology affiliated with the Stanford Woods Institute. "Their loss largely goes unnoticed, limiting our understanding of and ability to protect natural ecosystems." McCauley put it another way: "What we are doing in some ecosystems is akin to popping the hood on a car and disconnecting a few wires and rerouting a few hoses. All the parts are still there – the engine looks largely the same – but it's anyone's guess as to how or if the car will run."

By way of comparison, researcher Robert Dunbar, a Stanford Woods Institute senior fellow, recalled the historical chain effects of increasing demands on water from Central California's rivers. When salmon runs in these rivers slowed from millions of fish each year to a trickle, natural and agricultural land systems lost an important source of marine-derived fertilizer. These lost subsidies from the sea are now replaced by millions of dollars' worth of artificial fertilizer applications. "Humans can really snip one of these chains in half," Dunbar said.

INFORMATION:

This article was written byRob Jordan, communications writer for the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

Related Information:

Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment

http://woods.stanford.edu/

Stanford scientists document fragile land-sea ecological chain

2012-05-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Grande Vegas Presents Super Heroines Facebook Contest and Super Bonus Weekend

2012-05-21

Ever since Wonder Woman became the first big female super hero in 1942, super heroines from Batwoman to the Fantastic Four's Invisible Girl have been a force to be reckoned with. This month Grande Vegas Casino salutes the super women of our time with a Facebook Contest and Super Bonus Weekend. The Super Heroines Leaderboard Contests continue and there will be two more Super Heroines Live Raffles with $250 instant prizes this month.

A contest on the Grande Vegas Facebook Page this week gives players a chance to vote for their favorite super heroine and possibly win a ...

Controversy and Confusion Surround Proton Therapy

2012-05-21

In a new KLAS study titled "Proton Therapy 2012: Dollars, Decisions and Debates," the majority of participants said that concerns about market saturation and an estimated initial investment of $150-$200 million would likely prevent them from looking at proton therapy in the next five years.

"Besides cost, providers mention that ROI is a concern due to the patient referral base, staffing requirements, and ongoing maintenance costs," explained Monique Rasband, oncology research director and author of the report. "On the flip side, some currently ...

Hitting snooze on the molecular clock: Rabies evolves slower in hibernating bats

2012-05-21

Athens, Ga. – The rate at which the rabies virus evolves in bats may depend heavily upon the ecological traits of its hosts, according to researchers at the University of Georgia, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium. Their study, published May 17 in the journal PLoS Pathogens, found that the host's geographical location was the most accurate predictor of the viral rate of evolution. Rabies viruses in tropical and sub-tropical bat species evolved nearly four times faster than viral variants in bats in temperate ...

May GSA Bulletin postings take global geology tour

2012-05-21

Boulder, Colo., USA – GSA Bulletin papers posted online 3-18 May 2012 cover a variety of locations: the Coast Range basalt province, southwest Washington State, USA; the Faroe Islands of the northeast Atlantic margin; Wairarapa fault, North Island, New Zealand; the eastern Mediterranean Sea offshore of southern Crete; the southern central Andes of Argentina; the Adriatic Carbonate Platform of southwest Slovenia; the Atacama Desert, Chile; Questa caldera, northern New Mexico, USA; the Norwegian Caledonides; and Lake Tahoe, USA.

Petrology of the Grays River Volcanics, ...

Pollution teams with thunderclouds to warm atmosphere

2012-05-21

RICHLAND, Wash. -- Pollution is warming the atmosphere through summer thunderstorm clouds, according to a computational study published May 10 in Geophysical Research Letters. How much the warming effect of these clouds offsets the cooling that other clouds provide is not yet clear. To find out, researchers need to incorporate this new-found warming into global climate models.

Pollution strengthens thunderstorm clouds, causing their anvil-shaped tops to spread out high in the atmosphere and capture heat -- especially at night, said lead author and climate researcher ...

Acid in the brain

2012-05-21

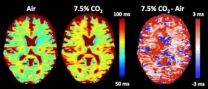

University of Iowa neuroscientist John Wemmie, M.D., Ph.D., is interested in the effect of acid in the brain. His studies suggest that increased acidity or low pH, in the brain is linked to panic disorders, anxiety, and depression. But his work also suggests that changes in acidity are important for normal brain activity too.

"We are interested in the idea that pH might be changing in the functional brain because we've been hot on the trail of receptors that are activated by low pH," says Wemmie, a UI associate professor of psychiatry. "The presence of these receptors ...

AGA presents cutting-edge research during DDW®

2012-05-21

San Diego, CA (May 18, 2012) — Clinicians, researchers and scientists from around the world will gather for Digestive Disease Week® (DDW) 2012, the largest and most prestigious gastroenterology meeting, from May 19-22, 2012, at the San Diego Convention Center, CA. DDW, the annual meeting of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, the AGA, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract.

AGA researchers will present ...

Web-based video enhances patient compliance with cancer screening

2012-05-21

Patients who watch an online instructional video are more likely to keep their appointments and arrive prepared for a scheduled colonoscopy than those who do not, according to a study by gastroenterologists at the University of Chicago Medicine.

The study, presented at the 2012 annual Digestive Diseases Week meeting in San Diego, CA, found that among patients age 50 to 65 – the primary target for colon cancer screening – those who watched the video were 40 percent less likely to cancel an appointment. That suggests many more cancers could be prevented or detected and ...

ESC Heart Failure Guidelines feature new recommendations on devices, drugs and diagnosis

2012-05-21

New recommendations on devices, drugs and diagnosis in heart failure were launched at the Heart Failure Congress 2012, 19-22 May, in Belgrade, Serbia, and published in the European Heart Journal.

The ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 were developed by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. The Congress is the HFA's main annual meeting.

An analysis of the most up to date clinical evidence in the field of heart failure by the ESC Guidelines task ...

Oxytocin improves brain function in children with autism

2012-05-21

Preliminary results from an ongoing, large-scale study by Yale School of Medicine researchers shows that oxytocin — a naturally occurring substance produced in the brain and throughout the body— increased brain function in regions that are known to process social information in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

A Yale Child Study Center research team that includes postdoctoral fellow Ilanit Gordon and Kevin Pelphrey, the Harris Associate Professor of Child Psychiatry and Psychology, will present the results on Saturday, May 19 at 3 p.m. ...