(Press-News.org) Having survived for more than 400 million years, the horseshoe crab is now under threat – primarily due to overharvest and habitat destruction. However, climatic changes may

also play a role. Researchers from the University of Gothenburg reveal how sensitive horseshoe crab populations are to natural climate change in a study recently published

in the scientific journal Molecular Ecology.

The horseshoe crab is often regarded as a living fossil, in that it has survived almost unchanged in terms of body design and lifestyle for more than 400 million years. Crabs similar to today's horseshoe crabs were walking the Earth long before the dinosaurs.

"Examining the genetic variation in populations of horseshoe crabs along the east coast of America has enabled us to track changes in population size over time," says Matthias Obst from the Department of Zoology at the University of Gothenburg, one of the authors of the study published in Molecular Ecology. "We noted a clear drop in the number of horseshoe

crabs at the end of the Ice Age, a period characterised by significant global warming."

Horseshoe crab important in the coastal food chain

"Our results also show that future climate change may further reduce the already vastly diminished population. Normally, horseshoe crabs would have no problem coping with climate change, but the ongoing destruction of their habitats make them much more sensitive."

Horseshoe crabs are an important part of the coastal food chain. Their blue blood is used to clinically detect toxins and bacteria. There are currently just four species of horseshoe crab

left: one in North America (Limulus polyphemus) and three in South East Asia (Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda, Tachypleus gigas and Tachypleus tridentatus).

All four species are under threat on account of over-harvesting for use as fish bait and in the pharmaceuticals industry. The destruction of habitats around the beaches that are the crabs'

breeding grounds has also contributed to the drop in numbers.

"The most decisive factor may be future changes in sea level and water temperature," says Obst. "Even if they are on a minimal scale such changes are likely to have a negative impact

on the crabs' distribution and reproduction."

INFORMATION:

Climate change affects horseshoe crab numbers

2010-10-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New approach to underweight COPD patients

2010-10-05

Malnutrition often goes hand in hand with COPD and is difficult to treat. In a recent study researchers at the University of Gothenburg, have come up with a new equation to calculate the energy requirement for underweight COPD patients. It is hoped that

this will lead to better treatment results and, ultimately, better quality of life for these patients.

Recently published in the International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, the study involved a total of 86 patients with an average age of 64. In contrast to studies in other countries, more than half ...

Interactive media improved patients’ understanding of cancer surgery by more than a third

2010-10-05

Patients facing planned surgery answered 36 per cent more questions about the procedure correctly if they watched an interactive multimedia presentation (IMP) rather than just talking to medical staff, according to research in the October issue of the urology journal BJUI.

Researchers from the University of Melbourne, Australia, randomised 40 patients due to undergo radical prostatectomy into two groups. The first group went through the standard surgery consent process, where staff explained the procedure verbally, and the second group watched the IMP.

Both sets of ...

Depression and distress not detected in majority of patients seen by nurses -- new study

2010-10-05

New research from the University of Leicester reveals that nursing staff have 'considerable difficulty' detecting depression and distress in patients.

Two new research studies led by Dr Alex Mitchell, consultant in psycho-oncology at Leicestershire Partnership Trust and honorary senior lecturer at the University of Leicester, highlight the fact that while nurses are at the front line of caring for people, they receive little training in mental health.

The researchers call for the development of short, simple methods to identify mood problems as a way of providing more ...

Bonn researchers use light to make the heart stumble

2010-10-05

Tobias Brügmann and his colleagues from the University of Bonn's Institute of Physiology I used a so-called "channelrhodopsin" for their experiments, which is a type of light sensor. At the same time, it can act as an ion channel in the cell membrane. When stimulated with blue light, this channel opens, and positive ions flow into the cell. This causes a change in the cell membrane's pressure, which stimulates cardiac muscle cells to contract.

"We have genetically modified mice to make them express channelrhodopsin in the heart muscle," explains Professor Dr. Bernd Fleischmann ...

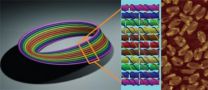

DNA art imitates life: Construction of a nanoscale Mobius strip

2010-10-05

The enigmatic Möbius strip has long been an object of fascination, appearing in numerous works of art, most famously a woodcut by the Dutchman M.C. Escher, in which a tribe of ants traverses the form's single, never-ending surface.

Scientists at the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University's and Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, led by Hao Yan and Yan Liu, have now reproduced the shape on a remarkably tiny scale, joining up braid-like segments of DNA to create Möbius structures measuring just 50 nanometers across—roughly the width of a virus particle. ...

Hebrew University research holds promise for development of new osteoporosis drug

2010-10-05

Jerusalem, October 4, 2010 – Researchers at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have discovered a group of substances in the body that play a key role in controlling bone density, and on this basis they have begun development of a drug for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis and other bone disorders.

The findings of the Hebrew University researchers have just been published in the American journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences).

The research group working on the project is headed by Prof. Itai Bab of the Bone Laboratory and Prof. Raphael ...

Disappearing glaciers enhanced biodiversity

2010-10-05

Biodiversity decreases towards the poles almost everywhere in the world, except along the South American Pacific coast. Investigating fossil clams and snails Steffen Kiel and Sven Nielsen at the Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel (CAU) could show that this unusual pattern originated at the end of the last ice age, 20.000 to 100.000 years ago. The retreating glaciers created a mosaic landscape of countless islands, bays and fiords in which new species developed rapidly – geologically speaking. The ancestors of the species survived the ice age in the warmer Chilean north.

The ...

A step toward lead-free electronics

2010-10-05

Research published today by materials engineers from the University of Leeds could help pave the way towards 100% lead-free electronics.

The work, carried out at the UK's synchrotron facility, Diamond Light Source, reveals the potential of a new manmade material to replace lead-based ceramics in countless electronic devices, ranging from inkjet printers and digital cameras to hospital ultrasound scanners and diesel fuel injectors.

European regulations now bar the use of most lead-containing materials in electronic and electrical devices. Ceramic crystals known as 'piezoelectrics' ...

Ancient Colorado river flowed backwards

2010-10-05

Palo Alto, CA—Geologists have found evidence that some 55 million years ago a river as big as the modern Colorado flowed through Arizona into Utah in the opposite direction from the present-day river. Writing in the October issue of the journal Geology, they have named this ancient northeastward-flowing river the California River, after its inferred source in the Mojave region of southern California.

Lead author Steven Davis, a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Global Ecology at the Carnegie Institution, and his colleagues* discovered the ancient river system ...

An eye for an eye

2010-10-05

Revenge cuts both ways in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Scientists of the University of Zurich, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Tel Aviv and Quinnipiaq Universities show that attacks by either side lead to violent retaliation from the other. Both Israelis and Palestinians may underestimate their own role in perpetuating the conflict.

A team of scientists from the University of Zurich, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Tel Aviv and Quinnipiaq Universities have found that attacks by both Israel and Palestinians lead to violent retaliation ...