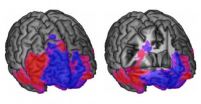

(Press-News.org) PASADENA, Calif.—The frontal lobes are the largest part of the human brain, and thought to be the part that expanded most during human evolution. Damage to the frontal lobes—which are located just behind and above the eyes—can result in profound impairments in higher-level reasoning and decision making. To find out more about what different parts of the frontal lobes do, neuroscientists at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) recently teamed up with researchers at the world's largest registry of brain-lesion patients. By mapping the brain lesions of these patients, the team was able to show that reasoning and behavioral control are dependent on different regions of the frontal lobes than the areas called upon when making a decision.

Their findings are described online this week in the early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The team analyzed data that had been acquired over a 30-plus-year time span by scientists from the University of Iowa's department of neurology—which has the world's largest lesion patient registry. They used that data to map brain activity in nearly 350 people with damage, or lesions, in their frontal lobes. The records included data on the performances of each patient while doing certain cognitive tasks.

By examining these detailed files, the researchers were able to see exactly which parts of the frontal lobes are critical for tasks like behavioral control and decision making. The intuitive difference between these two types of processing is something we encounter in our lives all the time. Behavioral control happens when you don't order an unhealthy chocolate sundae you desire and go running instead. Decision making based on reward, on the other hand, is more like trying to win the most money in Vegas—or indeed choosing the chocolate sundae.

"These are really unique data that could not have been obtained anywhere else in the world," explains Jan Glascher, lead author of the study and a visiting associate in psychology at Caltech. "To address the question that we were interested in, we needed both a large number of patients with very well-measured lesions in the brain, and also a very thorough assessment of their reasoning and decision-making abilities across a battery of tasks."

That quantification of the lesions as well as the different task measurements came from several decades of work led by two coauthors on the study: Hanna Damasio, Dana Dornsife Chair in Neuroscience at the University of Southern California (USC); and Daniel Tranel, professor or neurology and psychology at the University of Iowa.

"The patterns of lesions that impair specific tasks showed a very clear separation between those regions of the frontal lobes necessary for controlling behavior, and those necessary for how we give value to choices and how we make decisions," says Tranel.

Ralph Adolphs, Bren Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at Caltech and a coauthor of the study, says that aspects of what the team found had been observed previously using fMRI methods in healthy people. But, he adds, those previous studies only showed which parts of the brain are activated when people think or choose, but not which are the most critical areas, and which are less important.

"Only lesion mapping, like we did in the present study, can show you which parts of the brain are actually necessary for a particular task," he says. "This information is crucial, not only for basic cognitive neuroscience, but also for linking these findings to clinical relevance."

For example, several different parts of the brain might be activated when you are making a particular type of decision, explains Adolphs. If there is a lesion in one of these areas, the rest of your brain might be able to compensate, leaving little or no impairment. But if a lesion occurs in another area, you might wind up with a lifelong disability in decision making. Knowing which lesion leads to which outcome is something only this kind of detailed lesion study can provide, he says.

"That knowledge will be tremendously useful for prognosis after brain injury," says Adolphs. "Many people suffer injury to their frontal lobes—for instance, after a head injury during an automobile accident—but the precise pattern of the damage will determine their eventual impairment."

According to Tranel, the team is already working on their next project, which will use lesion mapping to look at how damage to particular brain regions can impact mood and personality. " There are so many other aspects of human behavior, cognition, and emotion to investigate here, that we've barely begun to scratch the surface," he says.

INFORMATION:

Other collaborators on the PNAS paper, "Lesion Mapping of Cognitive Control and Value-based Decision-making in the Prefrontal Cortex," were Lynn Paul, a senior research scientist at Caltech; David Rudrauf and Matt Calamia from the University of Iowa; and Antoine Bechara from USC. The study was supported by grants from the German Ministry of Research and Education, the National Institutes of Health, the Kiwanis Foundation, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Thinking and choosing in the brain

Caltech researchers study over 300 lesion patients

2012-08-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Multiple factors, including climate change, led to collapse and depopulation of ancient Maya

2012-08-22

TEMPE, Ariz. — A new analysis of complex interactions between humans and the environment preceding the 9th century collapse and abandonment of the Central Maya Lowlands in the Yucatán Peninsula points to a series of events — some natural, like climate change; some human-made, including large-scale landscape alterations and shifts in trade routes — that have lessons for contemporary decision-makers and sustainability scientists.

In their revised model of the collapse of the ancient Maya, social scientists B.L. "Billie" Turner and Jeremy "Jerry" A. Sabloff provide an up-to-date, ...

Time flies when you're having goal-motivated fun

2012-08-22

Though the seconds may tick by on the clock at a regular pace, our experience of the 'fourth dimension' is anything but uniform. When we're waiting in line or sitting in a boring meeting, time seems to slow down to a trickle. And when we get caught up in something completely engrossing – a gripping thriller, for example – we may lose sense of time altogether.

But what about the idea that time flies when we're having fun? New research from psychological science suggests that the familiar adage may really be true, with a caveat: time flies when we're have goal-motivated ...

Self-charging power cell converts and stores energy in a single unit

2012-08-22

Researchers have developed a self-charging power cell that directly converts mechanical energy to chemical energy, storing the power until it is released as electrical current. By eliminating the need to convert mechanical energy to electrical energy for charging a battery, the new hybrid generator-storage cell utilizes mechanical energy more efficiently than systems using separate generators and batteries.

At the heart of the self-charging power cell is a piezoelectric membrane that drives lithium ions from one side of the cell to the other when the membrane is deformed ...

NASA satellites see 2 intensifying northwestern Pacific tropical cyclones

2012-08-22

There's double trouble in the northwestern Pacific Ocean in the form of Typhoon Tembin and Tropical Storm Bolaven. NASA's Terra and Aqua satellites teamed up to provide a look at both storms in one view.

The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument flies onboard NASA's Aqua and Terra satellites and the MODIS instrument on each captured a storm when both satellites flew over them on August 21 after midnight (Eastern Daylight Time). The two MODIS images which featured Bolaven and Tembin over the Philippine Sea were combined by NASA's MODIS Rapid ...

Many options, good outcomes, for early-stage follicular lymphoma

2012-08-22

A University of Rochester Medical Center study published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, challenges treatment guidelines for early stage follicular lymphoma, concluding that six different therapies can bring a remission, particularly if the patient is carefully examined and staged at diagnosis.

The research underlines the fact that when cancer strikes, modern patients and their oncologists across the United States are taking many diverse treatment paths when there is scant data to support one method over another. This study suggests that the old standard approach ...

Sanctuary chimps show high rates of drug-resistant staph

2012-08-22

Chimpanzees from African sanctuaries carry drug-resistant, human-associated strains of the bacteria Staphlyococcus aureus, a pathogen that the infected chimpanzees could spread to endangered wild ape populations if they were reintroduced to their natural habitat, a new study shows.

The study by veterinarians, microbiologists and ecologists was the first to apply the same modern sequencing technology of bacterial genomes used in hospitals to track the transmission of staph from humans to African wildlife. The results were published Aug. 21 by the American Journal of Primatology.

Drug-resistant ...

'Electronic nose' prototype developed

2012-08-22

RIVERSIDE, Calif. (www.ucr.edu) — Research by Nosang Myung, a professor at the University of California, Riverside, Bourns College of Engineering, has enabled a Riverside company to develop an "electronic nose" prototype that can detect small quantities of harmful airborne substances.

Nano Engineered Applications, Inc., an Innovation Economy Corporation company, has completed the prototype which is based on intellectual property exclusively licensed from the University of California. The device has potential applications in agriculture (detecting pesticide levels), industrial ...

Low oxygen levels may decrease life-saving protein in spinal muscular atrophy

2012-08-22

Investigators at Nationwide Children's Hospital may have discovered a biological explanation for why low levels of oxygen advance spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) symptoms and why breathing treatments help SMA patients live longer. The findings appear in Human Molecular Genetics.*

SMA is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that causes muscle damage and weakness leading to death. Respiratory support is one of the most common treatment options for severe SMA patients since respiratory deficiencies increase as the disease progresses. Clinicians have found that successful ...

Compounds shown to thwart stubborn pathogen's social propensity

2012-08-22

MADISON – Acinetobacter baumanni, a pathogenic bacterium that is a poster child of deadly hospital acquired infections, is one tough customer.

It resists most antibiotics, is seemingly immune to disinfectants, and can survive desiccation with ease. Indeed, the prevalence with which it infects soldiers wounded in Iraq earned it the nickname "Iraqibacter."

In the United States, it is the bane of hospitals, opportunistically infecting patients through open wounds, catheters and breathing tubes. Some estimates suggest it kills tens of thousands of people annually.

But ...

ORNL technology moves scientists closer to extracting uranium from seawater

2012-08-22

Fueling nuclear reactors with uranium harvested from the ocean could become more feasible because of a material developed by a team led by the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

The combination of ORNL's high-capacity reusable adsorbents and a Florida company's high-surface-area polyethylene fibers creates a material that can rapidly, selectively and economically extract valuable and precious dissolved metals from water. The material, HiCap, vastly outperforms today's best adsorbents, which perform surface retention of solid or gas molecules, atoms ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Teens using AI meal plans could be eating too few calories — equivalent to skipping a meal

Inconsistent labeling and high doses found in delta-8 THC products: JSAD study

Bringing diabetes treatment into focus

Iowa-led research team names, describes new crocodile that hunted iconic Lucy’s species

One-third of Americans making financial trade-offs to pay for healthcare

Researchers clarify how ketogenic diets treat epilepsy, guiding future therapy development

PsyMetRiC – a new tool to predict physical health risks in young people with psychosis

Island birds reveal surprising link between immunity and gut bacteria

Research presented at international urology conference in London shows how far prostate cancer screening has come

Further evidence of developmental risks linked to epilepsy drugs in pregnancy

Cosmetic procedures need tighter regulation to reduce harm, argue experts

How chaos theory could turn every NHS scan into its own fortress

Vaccine gaps rooted in structural forces, not just personal choices: SFU study

Safer blood clot treatment with apixaban than with rivaroxaban, according to large venous thrombosis trial

Turning herbal waste into a powerful tool for cleaning heavy metal pollution

Immune ‘peacekeepers’ teach the body which foods are safe to eat

AAN issues guidance on the use of wearable devices

In former college athletes, more concussions associated with worse brain health

Racial/ethnic disparities among people fatally shot by U.S. police vary across state lines

US gender differences in poverty rates may be associated with the varying burden of childcare

3D-printed robotic rattlesnake triggers an avoidance response in zoo animals, especially species which share their distribution with rattlers in nature

Simple ‘cocktail’ of amino acids dramatically boosts power of mRNA therapies and CRISPR gene editing

Johns Hopkins scientists engineer nanoparticles able to seek and destroy diseased immune cells

A hidden immune circuit in the uterus revealed: Findings shed light on preeclampsia and early pregnancy failure

Google Earth’ for human organs made available online

AI assistants can sway writers’ attitudes, even when they’re watching for bias

Still standing but mostly dead: Recovery of dying coral reef in Moorea stalls

3D-printed rattlesnake reveals how the rattle is a warning signal

Despite their contrasting reputations, bonobos and chimpanzees show similar levels of aggression in zoos

Unusual tumor cells may be overlooked factors in advanced breast cancer

[Press-News.org] Thinking and choosing in the brainCaltech researchers study over 300 lesion patients