(Press-News.org) In the foothills of the Santa Cruz Mountains two closely related species of mice share a habitat and a genetic lineage, but have very different social lives. The California mouse (Peromyscus californicus) is characterized by a lifetime of monogamy; the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) is sexually promiscuous.

Researchers at the University of California Berkeley recently showed how these differences in sexual behavior impact the bacteria hosted by each species as well as the diversity of the genes that control immunity. The results were published in the May 2012 edition of PLoS One.

Monogamy is a fairly rare trait in mammals, possessed by only five percent of species. Rarely do two related, but socially distinguishable, species live side-by-side. This makes these two species of mice interesting subjects for Matthew MacManes, a National Institutes of Health-sponsored post-doctoral fellow at UC Berkeley.

Through a series of analyses, MacManes and researchers from the Lacey Lab examined the differences between these two species on the microscopic and molecular levels. They discovered that the lifestyles of the two mice had a direct impact on the bacterial communities that reside within the female reproductive tract. Furthermore, these differences correlate with enhanced diversifying selection on genes related to immunity against bacterial diseases.

Bacteria live on every part of our bodies and have distinctive ecologies. The first step of MacManes project involved testing the bacterial communities that resided in the vaginas of both species of mice — the most relevant area for a study about monogamous and promiscuous mating systems.

Next, MacManes performed a genetic analysis on the variety of DNA present, revealing hundreds of different types of bacteria present in each species. He found that the promiscuous deer mouse had twice the bacterial diversity as the monogamous California mouse. Since many bacteria cause sexually transmitted infections (like chlamydia or gonorrhea), he used the diversity of bacteria as a proxy for risk of disease. Results of the study were published in Naturwissenschaften in October 2011.

But this wasn't the end of the exploration.

"The obvious next question was, does the bacterial diversity in the promiscuous mice translate into something about the immune system, or how the immune system functions?" MacManes asked.

MacManes hypothesized that selective pressures caused by generation after generation of bacterial warfare had fortified the genomes of the promiscuous deer mouse against the array of bacteria it hosts.

To find out, he sequenced genes related to immune function of the two mice species and compared each species' versions of one important immunity gene, MHC-DQa. Some forms of genes (alleles) are better at recognizing different pathogens than others. If an individual has only a single common allele, it may only recognize a limited set of bacterial pathogens. In contrast, if an individual has two different alleles it may recognize a more diverse set of bacterial pathogens, and thus be more protected against infection.

Based on a comparison of the two species' genotypes he confirmed that the promiscuous mice had much more diversity in the genes related to their immune system.

"The promiscuous mice, by virtue of their sexual system, are in contact with more individuals and are exposed to a lot more bacteria," MacManes said. "They need a more robust immune system to fend off all of the bugs that they're exposed to."

The results, published in PLoS One, match findings in humans and other species with differential mating habits. They show that differences in social behavior can lead to changes in the selection pressures and gene-level evolutionary changes in a species.

Motivated by this result, MacManes began work on a project that looked to understand the genetics of a far more complex behavior—whether to stay at home with relatives, or to disperse to a new burrow.

Scientists have been sequencing and exploring the genome for more than a decade. For much of this time, studies have been limited to the most common and well-known species: humans, lab-mice, and fruit flies. But in recent years, as the cost of sequencing has dropped and the methods of exploring genomic information have improved, researchers have begun to analyze other less traditional organisms.

MacManes project was one of the first studies to use next-generation gene sequencing and high performance computers to assess the influence of behavior on genes in a non-model species.

"This is a field that people have always been interested in, but the tools hadn't existed yet for people to really understand how complex the mechanisms were," MacManes said.

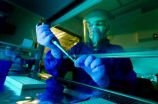

Next-generation sequencing determines the order of the nucleotide bases in a molecule of DNA by breaking the double helix into short fragments and rapidly analyzing thousands of chunks at a time. Once hundreds of millions of genetic snippets have been read out by a DNA sequencer, they must be assembled into a single genome, or mapped to a reference genome, and compared to other genetic sequences to be useful.

"The sequencing is something that you can do in any molecular biology lab—that's easy," MacManes said. "But when you try to do an analysis of the data, you get back something like several billion base pairs of data. How to actually analyze the data is the real issue."

As a National Science Foundation (NSF) graduate research fellow, MacManes learned that researchers could access NSF supercomputers through the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) to analyze datasets too big for their university laboratory clusters. Once he had his sequences, MacManes turned to the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) at The University of Texas at Austin, a lead partner in XSEDE and home to the Ranger supercomputer.

"When we first started using Ranger, it was a breakthrough moment for us," he said. "We had the data set, but we didn't have any way to do anything with it. Ranger was really our first real chance at analyzing this data. "

The alignment and analysis that MacManes accomplished on Ranger in a few weeks would have taken years with his local resources. It organized the data so MacManes could find insights about the relationship between genes and behavior.

"The ability to isolate and compare genetic differences related to social behavior using advanced computing is a fascinating application of emerging technologies," said Jennifer Verodolin, a researcher specializing in social rodents at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center in Durham, North Carolina. "We often see individual and population-level social and mating differences within the same species. While ecological factors are linked to this variation, these sophisticated new tools will now allow us to see the genetic signature of how natural selection has shaped behavior."

Mating systems, and social systems more broadly, are important to basic evolutionary biology, MacManes asserted. "The things an animal does, the way it behaves, and who it interacts with, are important to natural selection. These factors can cause immunogenes to evolve at a much faster rate, or slower in the case of monogamous mice. That connection is important and probably under-recognized."

Monogamy and promiscuity are only one of a variety of social behaviors that are thought to influence gene expression. MacManes' current research involves analyzing gene expression in the hippocampus brain region of tuco tucos (a sort of South American gopher) who live together in social groups and others who live independently. He is hoping to find what differentiates the social animals from the loners and what impact this change in their behavior has on their genetic profile.

"Now that we have these new sequencing technologies, people are going to be really interested in looking at the mechanisms that underlie these behaviors," MacManes said. "How might genes control what we do, and how we behave? We're going to see an explosion in these studies where people start to understand the very basic genetic mechanism for all sorts of behaviors that we know are out there."

INFORMATION:

Monogamy and the immune system

UC Berkeley researchers use the Ranger supercomputer to identify genetic differences related to the social lives of mammals

2012-08-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cardiovascular risk evaluation for all men should include assessment of sexual function

2012-08-31

(CHICAGO)-- Assessment of sexual function should be incorporated into cardiovascular risk evaluation for all men, regardless of the presence or absence of known cardiovascular disease, according to Dr. Ajay Nehra, lead author of a report by the Princeton Consensus (Expert Panel) Conference, a collaboration of 22 international, multispecialty researchers. Nehra is vice chairperson, professor and director of Men's Health in the Department of Urology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago.

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a red flag in younger men, less than 55 years of ...

Ancient genome reveals its secrets

2012-08-31

This release is available in German.

The analyses of an international team of researchers led by Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, show that the genetic variation of Denisovans was extremely low, suggesting that although they were present in large parts of Asia, their population was never large for long periods of time. In addition, a comprehensive list documents the genetic changes that set apart modern humans from their archaic relatives. Some of these changes concern genes that are associated with brain function ...

Microbes help hyenas communicate via scent

2012-08-31

EAST LANSING, Mich. — Bacteria in hyenas' scent glands may be the key controllers of communication.

The results, featured in the current issue of Scientific Reports, show a clear relationship between the diversity of hyena clans and the distinct microbial communities that reside in their scent glands, said Kevin Theis, the paper's lead author and Michigan State University postdoctoral researcher.

"A critical component of every animal's behavioral repertoire is an effective communication system," said Theis, who co-authored the study with Kay Holekamp, MSU zoologist. ...

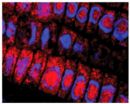

Moving toward regeneration

2012-08-31

KANSAS CITY, MO—The skin, the blood, and the lining of the gut—adult stem cells replenish them daily. But stem cells really show off their healing powers in planarians, humble flatworms fabled for their ability to rebuild any missing body part. Just how adult stem cells build the right tissues at the right times and places has remained largely unanswered.

Now, in a study published in an upcoming issue of Development, researchers at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research describe a novel system that allowed them to track stem cells in the flatworm Schmidtea mediterranea. ...

Health reform: How community health centers could offer better access to subspecialty care

2012-08-31

FINDINGS:

The Affordable Care Act will fund more community health centers, making primary care more accessible to the underserved. But this may not necessarily lead to better access to subspecialty care.

In a new study, researchers from the David Geffen School of Medicine and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Clinical Scholars program at UCLA and colleagues investigated the ways in which community health centers access subspecialty care. They identified six major models and determined which of those six offered the best access:

Tin cup ...

Researchers measure photonic interactions at the atomic level

2012-08-31

DURHAM, N.C. -- By measuring the unique properties of light on the scale of a single atom, researchers from Duke University and Imperial College, London, believe that they have characterized the limits of metal's ability in devices that enhance light.

This field is known as plasmonics because scientists are trying to take advantage of plasmons, electrons that have been "excited" by light in a phenomenon that produces electromagnetic field enhancement. The enhancement achieved by metals at the nanoscale is significantly higher than that achievable with any other material.

Until ...

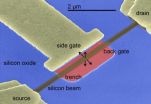

'Nanoresonators' might improve cell phone performance

2012-08-31

"There is not enough radio spectrum to account for everybody's handheld portable device," said Jeffrey Rhoads, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Purdue University.

The overcrowding results in dropped calls, busy signals, degraded call quality and slower downloads. To counter the problem, industry is trying to build systems that operate with more sharply defined channels so that more of them can fit within the available bandwidth.

"To do that you need more precise filters for cell phones and other radio devices, systems that reject noise and allow signals ...

Discovery may help protect crops from stressors

2012-08-31

VIDEO:

Scientists at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies have discovered a key genetic switch by which plants control their response to ethylene gas, a natural plant hormone best known for...

Click here for more information.

LA JOLLA, CA----Scientists at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies have discovered a key genetic switch by which plants control their response to ethylene gas, a natural plant hormone best known for its ability to ripen fruit, but which, under ...

Biophysicists unravel secrets of genetic switch

2012-08-31

When an invading bacterium or virus starts rummaging through the contents of a cell nucleus, using proteins like tiny hands to rearrange the host's DNA strands, it can alter the host's biological course. The invading proteins use specific binding, firmly grabbing onto particular sequences of DNA, to bend, kink and twist the DNA strands. The invaders also use non-specific binding to grasp any part of a DNA strand, but these seemingly random bonds are weak.

Emory University biophysicists have experimentally demonstrated, for the fist time, how the nonspecific binding of ...

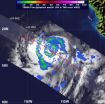

NASA spotted hot towers in Ileana that indicated its increase to hurricane status

2012-08-31

Hot Towers are towering clouds that emit a tremendous amount of latent heat (thus, called "hot"). NASA research indicates that whenever a hot tower is spotted, a tropical cyclone will likely intensify. Less than 14 hours after the TRMM satellite captured an image of Ileana's rainfall and cloud heights, Ileana strengthened into a hurricane on Aug. 29.

NASA's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite captured a view of Ileana's rainfall rates on Aug. 29 at 2:17 a.m. EDT and saw the heaviest rainfall rates, near 50 mm (2.0 inches) per hour in a band of thunderstorms ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Low-temperature-activated deployment of smart 4D-printed vascular stents

Clinical relevance of brain functional connectome uniqueness in major depressive disorder

For dementia patients, easy access to experts may help the most

YouTubers love wildlife, but commenters aren't calling for conservation action

New study: Immune cells linked to Epstein-Barr virus may play a role in MS

AI tool predicts brain age, cancer survival, and other disease signals from unlabeled brain MRIs

Peak mental sharpness could be like getting in an extra 40 minutes of work per day, study finds

No association between COVID-vaccine and decrease in childbirth

AI enabled stethoscope demonstrated to be twice as efficient at detecting valvular heart disease in the clinic

Development by Graz University of Technology to reduce disruptions in the railway network

Large study shows scaling startups risk increasing gender gaps

Scientists find a black hole spewing more energy than the Death Star

A rapid evolutionary process provides Sudanese Copts with resistance to malaria

Humidity-resistant hydrogen sensor can improve safety in large-scale clean energy

Breathing in the past: How museums can use biomolecular archaeology to bring ancient scents to life

Dementia research must include voices of those with lived experience

Natto your average food

Family dinners may reduce substance-use risk for many adolescents

Kumamoto University Professor Kazuya Yamagata receives 2025 Erwin von Bälz Prize (Second Prize)

Sustainable electrosynthesis of ethylamine at an industrial scale

A mint idea becomes a game changer for medical devices

Innovation at a crossroads: Virginia Tech scientist calls for balance between research integrity and commercialization

Tropical peatlands are a major source of greenhouse gas emissions

From cytoplasm to nucleus: A new workflow to improve gene therapy odds

Three Illinois Tech engineering professors named IEEE fellows

Five mutational “fingerprints” could help predict how visible tumours are to the immune system

Rates of autism in girls and boys may be more equal than previously thought

Testing menstrual blood for HPV could be “robust alternative” to cervical screening

Are returning Pumas putting Patagonian Penguins at risk? New study reveals the likelihood

Exposure to burn injuries played key role in shaping human evolution, study suggests

[Press-News.org] Monogamy and the immune systemUC Berkeley researchers use the Ranger supercomputer to identify genetic differences related to the social lives of mammals