(Press-News.org) Jerusalem, Sept. 3, 2012 – Researchers at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem have discovered that a neuronal pathway -- part of the autonomic nervous system -- reaches the bones and participates in the control of bone development.

The newly discovered pathway has a key role in controlling bone density during adolescence, which in turn determines the skeletal resistance to fracture throughout one's entire life, say the researchers. They emphasize that understanding the mechanisms connecting the brain and the bones could have implications for possible future therapies to better deal with osteoporosis and various neural disorders.

The findings of the Hebrew University team are published this week in the American journal PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences).

Participants in the project were researchers from the Hebrew University's Bone Laboratory, headed by Prof. Itai Bab, in collaboration with Prof. Raz Yirmia, the head of the Laboratory for Brain and Behavioral Research, plus research students Alon Bajayo and Vardit Kram and master's students Arik Bar and Marilyn Bachar. Additional collaborators were Dr. Adam Denes from the University of Manchester, UK, and Prof. Alberta Zallone from the University of Bari, Italy.

The autonomic nervous system, by which the brain monitors and regulates the physiological functioning of the internal organs, includes two subsystems, called "sympathetic" and "parasympathetic." Each of these subsystems has its own, distinct neural pathways. In general, the sympathetic nervous system is perhaps best known for mediating the neuronal and hormonal responses to stress. The sympathetic pathway, on the other hand, generally works to promote maintenance of the body at rest.

Previous studies by the Hebrew University researchers and others showed that the sympathetic nervous system reaches the skeleton and slows down bone development. On the other hand, until now, there was no information on skeletal parasympathetic activity there.

To demonstrate that there are indeed parasympathetic responses in the skeleton, the researchers injected a weakened rabies virus into the thigh bones of mice. The rabies virus has a unique feature -- it migrates from its injection site in the periphery along nerve fibers towards the brain. Following injection to the thigh bone, the virus was found in the brain in regions known to be specific for the parasympathetic subsystem.

In the past, these same researchers reported that the activity of a protein called interleukin-1 influences bone development. Now they noticed that this influence is very similar to that of the parasympathetic subsystem. Indeed, the researchers showed that deactivating interleukin-1 activity in the brain of laboratory mice paralyzes parasympathetic activity in the bone and slows down skeletal development. They further found that the newly discovered neuronal pathway, which includes interleukin-1 in the brain and the parasympathetic subsystem, also controls the heart rate.

As in the bone and the heart, the new pathway might have an important function as well in other organs controlled by the autonomic nervous system. Prof. Yirmiya said that "low bone density and osteoporosis often appear together with neuropsychiatric disorders such as depression, Alzheimer's disease and epilepsy, since interleukin-1 in the brain and the parasympathetic system are often damaged in these disorders. Finding the disease mechanisms in these cases has a huge potential for the development of new therapies," he added.

"The connection between the brain and the bone in general and the involvement of the newly discovered pathway in particular is a new area of research about which we still know very little," said Prof. Bab. "The new findings, discovered in our Hebrew University laboratories, highlight for the first time an important physiologic role for the connection between interleukin-1 in the brain and the autonomic nervous system.

The research has been conducted as part of a project to study the connection between the activity of interleukin-1 in the brain, the parasympathetic system and the skeleton. It was supported by the German-Israeli Foundation for Scientific Research and Development and by the Israel Science Foundation.

INFORMATION:

New neural pathway controlling skeletal development discovered

2012-09-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Broader approach provides new insight into diabetes genes

2012-09-04

Using a new method, diabetes researchers at Lund University, Sweden, have been able to reveal more of the genetic complexity behind type 2 diabetes. The new research findings have been achieved as a result of access to human insulin-producing cells from deceased donors and by not only studying one gene variant, but many genes and how they influence the level of the gene in pancreatic islets and their effect on insulin secretion and glucose control of the donor.

"With this approach, we can explain 25 per cent of variations in blood sugar levels. Previously, the best studies ...

New ESF-cofunded feasibility study calls for a single European researcher development framework

2012-09-04

The aim of the study was to assess the applicability across Europe of a generic framework for the professional development of researchers based on the Vitae Researcher Development Framework (RDF). The RDF is a UK-context framework set up with the purpose to better define researcher's professional profiles and to develop guidance for the continuous professional development of researchers. The report reveals that there is a real demand among researchers for a more structured approach towards researcher´s professional development and active career planning.

This new ESF-co-funded ...

Anchoring proteins influence glucose metabolism and insulin release

2012-09-04

HEIDELBERG, 3 September 2012 – Scientists from the United States and Sweden have discovered a new control point that could be important as a drug target for the treatment of diabetes and other metabolic diseases. A-kinase anchoring proteins or AKAPs are known to influence the spatial distribution of kinases within the cell, crucial enzymes that control important molecular events related to the regulation of glucose levels in the blood. In a new study published in The EMBO Journal, the team of researchers led by Simon Hinke and John Scott reveal for the first time that AKAPs ...

PharmaNet system dramatically reduced inappropriate prescriptions of potentially addictive drugs

2012-09-04

A centralized prescription network providing real-time information to pharmacists in British Columbia, Canada, resulted in dramatic reductions in inappropriate prescriptions for opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines, widely used and potentially addictive drugs. The findings are reported in a study in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

The study found that PharmaNet, a real-time prescription system implemented in BC pharmacies in July 1995, reduced potentially inappropriate prescriptions for opioids and benzodiazepines in two groups of patients — those on social ...

Canada should remove section of Criminal Code that permits physical punishment of children

2012-09-04

To promote good parenting, Canada should remove section 43 of its Criminal Code because it sends the wrong message that using physical punishment to discipline children is acceptable, argues Dr. John Fletcher, Editor-in-Chief, CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) in an editorial.

Section 43 of the Criminal Code of Canada states "…a parent is justified in using force by way of correction…if the force does not exceed what is reasonable under the circumstances."

The debate over whether spanking children is acceptable as a disciplinary tool for parents or whether ...

Ovarian cancer cells hijack surrounding tissues to enhance tumor growth

2012-09-04

Tumor growth is dependent on interactions between cancer cells and adjacent normal tissue, or stroma. Stromal cells can stimulate the growth of tumor cells; however it is unclear if tumor cells can influence the stroma. In the September issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, researchers at MD Anderson Cancer Center report that ovarian cancer cells activate the HOXA9 gene to compel stromal cells to create an environment that supports tumor growth.

Honami Naora and colleagues found that expression of HOXA9 was correlated with poor outcomes in cancer patients and ...

JCI early table of contents for Sept. 4, 2012

2012-09-04

Ovarian cancer cells hijack surrounding tissues to enhance tumor growth

Tumor growth is dependent on interactions between cancer cells and adjacent normal tissue, or stroma. Stromal cells can stimulate the growth of tumor cells; however it is unclear if tumor cells can influence the stroma. In this issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, researchers at MD Anderson Cancer Center report that ovarian cancer cells activate the HOXA9 gene to compel stromal cells to create an environment that supports tumor growth.

Honami Naora and colleagues found that expression ...

EARTH: Antarctic trees surprise scientists

2012-09-04

Alexandria, VA – "Warm" and "Antarctica" are not commonly used in the same sentence; however, for scientists, "warm" is a relative term. A team of researchers has discovered that, contrary to previous thinking, the Antarctic continent has experienced periods of warmth since the onset of its most recent glaciation.

Lodged in ocean sediment nearly 20 million years old, ancient pollen and leaf wax samples taken from the Ross Ice Shelf suggest that two brief warming spells, each of which lasted less than 30,000 years, punctuated the omnipresent cold of Antarctica. Warm, ...

Binding sites for LIN28 protein found in thousands of human genes

2012-09-04

A study led by researchers at the UC San Diego Stem Cell Research program and funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) looks at an important RNA binding protein called LIN28, which is implicated in pluripotency and reprogramming as well as in cancer and other diseases. According to the researchers, their study – published in the September 6 online issue of Molecular Cell – will change how scientists view this protein and its impact on human disease.

Studying embryonic stem cells and somatic cells stably expressing LIN28, the researchers defined ...

Spinach power gets a big boost

2012-09-04

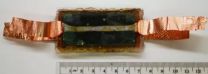

An interdisciplinary team of researchers at Vanderbilt University have developed a way to combine the photosynthetic protein that converts light into electrochemical energy in spinach with silicon, the material used in solar cells, in a fashion that produces substantially more electrical current than has been reported by previous "biohybrid" solar cells.

The research was reported online on Sep. 4 in the journal Advanced Materials and Vanderbilt has applied for a patent on the combination.

"This combination produces current levels almost 1,000 times higher than we were ...