(Press-News.org) A North Carolina State University researcher has created a roadmap to areas of the brain associated with affective aggression in mice. This roadmap may be the first step toward finding therapies for humans suffering from affective aggression disorders that lead to impulsive violent acts.

Affective aggression differs from defensive aggression or premeditated aggression used by predators, in that the role of affective aggression isn't clear and could be considered maladaptive. NC State neurobiologist Dr. Troy Ghashghaei was interested in finding the areas of the brain engaged with this type of aggressive behavior. Using mice that had been specially bred for affective aggression by his research associate Dr. Derrick L Nehrenberg, Ghashghaei and former undergraduate student Atif Sheikh were able to locate the regions in the mouse brain that switched on and those that were off when the mice displayed affective aggression.

"The brain works by using clusters of neurons that cross communicate at extremely rapid rates, much like a computer," Ghashghaei explains. "One region will process a stimulus, and then that region sends messages to other clusters within the brain, like circuits within a computer. We looked at how the switches flipped in the brains of aggressive mice, and compared that with the brains of completely nonaggressive mice in the same setting, to see how the two processed the situation differently."

They found that affectively aggressive mice demonstrated a large difference in the way their "executive centers" operated when the mice encountered another mouse. "Sensory inputs come in and are sent to the executive center, the part of the brain that decides how to respond to the input," Ghashghaei says. "In the meantime, the information about the response you made gets processed back with either a pleasant or unpleasant association."

According to Ghashghaei, the affectively aggressive mice could react violently because their brains are hardwiredto respond to certain situations aggressively without assessing whether their response to the situation is appropriate or without regard to the behavior's consequences. In addition, affectively aggressive mice may be forming pleasant associations with their violent displays, which would reinforce their aggressive tendencies.

"We cannot say which of the two possibilities underlie the persistent aggressive displays by our mice," Ghashghaei says, "but we can see that the patterns of neuronal activity are very different in the executive centers of these mice. Additionally, there are differences in the neuronal clusters involved with creating pleasant or unpleasant associations to the stimulus or their response. That gives us a few starting spots to begin identifying the mechanisms that underlie these profound behavioral differences."

The regions of the brain that were involved in affective aggression in the mice are similar across all mammalian species. Ghashghaei hopes that his findings in mice will be useful to researchers studying violent behavior in humans, as well as aggression in other animals.

"With the brain, just knowing where to start looking is huge," Ghashghaei says. "Once you have a few targets, you can tease out the possibilities and get to the heart of the problem. We are confident that manipulation of some of the identified targets in our study will disrupt displays of affective aggression in our mouse model."

The researchers' findings appear online in Brain Structure and Function.

###

Note to editors: Abstract follows.

"Identification of neuronal loci involved with displays of affective aggression in NC900 mice"

Authors: Derrick L. Nehrenberg, Atif Sheikh, H. Troy Ghashghaei, North Carolina State University

Published: Brain Structure and Function

Abstract:

Aggression is a complex behavior that is essential for survival. Of the various forms of aggression, impulsive violent displays without prior planning or deliberation are referred to as affective aggression. Affective aggression is thought to be caused by aberrant perceptions of, and consequent responses to, threat. Understanding the neuronal networks that regulate affective aggression is pivotal to development of novel approaches to treat chronic affective aggression. Here, we provide a detailed anatomical map of neuronal activity in the forebrain of two inbred lines of mice that were selected for low (NC100) and high (NC900) affective aggression. Attack behavior was induced in male NC900 mice by exposure to an unfamiliar male in a novel environment. Forebrain maps of c-Fos+ nuclei, which are surrogates for neuronal activity during behavior, were then generated and analyzed. NC100 males rarely exhibited affective aggression in response to the same stimulus, thus their forebrain c-Fos maps were utilized to identify unique patterns of neuronal activity in NC900s. Quantitative results indicated robust differences in the distribution patterns and densities of c-Fos+ nuclei in distinct thalamic, subthalamic, and amygdaloid nuclei, together with unique patterns of neuronal activity in the nucleus accumbens and the frontal cortices. Our findings implicate these areas as foci regulating differential behavioral responses to an unfamiliar male in NC900 mice when expressing affective aggression. Based on the highly conserved patterns of connections and organization of neuronal limbic structures from mice to humans, we speculate that neuronal activities in analogous networks may be disrupted in humans prone to maladaptive affective aggression.

END

Vitamin D has been touted for its beneficial effects on a range of human systems, from enhancing bone health to reducing the risk of developing certain cancers. But it does not improve cholesterol levels, according to a new study conducted at The Rockefeller University Hospital. A team of scientists has shown that, at least in the short term, cholesterol levels did not improve when volunteers with vitamin D deficiency received mega-doses of vitamin D. The finding is published in the journal Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology.

The researchers, led by Manish ...

BEER-SHEVA, ISRAEL, September 4, 2012 -- Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (BGU) researchers have determined that preeclampsia is a significant risk factor for long-term health issues, such as chronic hypertension and hospitalizations later in life. The findings from the retrospective cohort study were just published in the Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine.

Thousands of women and their babies die or get very sick from preeclampsia; it affects approximately 5 to 8 percent of all pregnancies. It is a rapidly progressive condition characterized by high blood ...

HOUSTON – Biologic therapies developed in the last decade for rheumatoid arthritis are not associated with an increased risk of cancer when compared with traditional treatments for the condition, according to new research from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

The study, published in The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), is the largest systematic review evaluating the risk of developing any malignancy among rheumatoid arthritis patients using approved biologic response modifiers (BRMs), several of which include tumor necrosis factor ...

(Edmonton) University of Alberta led research shows an elk's personality type is a big factor in whether or not it survives the hunting season.

Data collected from GPS collars on more than 100 male and female elk in southwestern Alberta showed U of A researchers the study population could be divided into two categories: bold runners and shy hiders:

Bold-runner elk, both males and females, moved quickly through the study area and preferred to graze in open fields for the most abundant and nutritious grass. GPS data showed shy hiders stayed and grazed on the sparse vegetation ...

The protection of the savings of the elderly—one of the primary goals of Medicare—is under threat from a combination of spiraling healthcare costs and increased longevity. As the government attempts to reduce Medicare costs, one suggestion is that the elderly could pay a larger proportion of the costs of their healthcare. But exactly how much would this be and what impact would it have on their finances? A new study by Amy Kelley at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and her colleagues, funded by the National Institute on Aging, aims to identify the portion of wealth ...

Tropical Storm John had about one day of fame in the Eastern Pacific. Born Tropical Depression 10, it intensified into Tropical Storm John on Sept. 2 at 5 a.m. EDT and maintained maximum sustained winds of 40 mph (65 kmh) until it weakened back into a depression on Monday, Sept. 3 at 11 p.m. EDT.

NASA's Aqua satellite flew over John on Sept. 3 at 2041 UTC (4:41 p.m. EDT) during its brief time as a tropical storm and noticed convection (rising air that forms thunderstorms that make up the storm) and coldest cloud top temperatures seemed to be limited to the northeastern ...

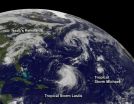

Over the weekend of Aug. 31 to Sept. 2, Tropical Storm Leslie's maximum sustained winds were pretty constant and satellite imagery from NASA's Aqua and Terra satellites confirm the steadiness of the storm. That story is expected to change later this week however, as Leslie nears Bermuda and is expected to reach hurricane strength. Meanwhile, Leslie is still about the same strength today, Sept. 4 because of wind shear.

Two visible images from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer or MODIS instrument that flies onboard both of NASA's Aqua and Terra satellites ...

Tiny Tropical Storm Michael formed today, Sept. 4, from the thirteenth tropical depression in the Atlantic Ocean, but it seems that wind shear will make Michael struggle to intensify over the next couple of days like his "sister" Tropical Storm Leslie. Isaac's remnants blanket the U.S. east coast.

Leslie has been a tropical storm since late Aug. and has not yet reached hurricane strength because of wind shear, although that is expected to change. Isaac's remnants are also struggling, but struggling to get off the land and back into the Atlantic Ocean. Isaac's remnants ...

JUPITER, FL - Scientists on the Florida campus of The Scripps Research Institute have designed a compound that shows promise as a potential therapy for one of the diseases closely linked to fragile X syndrome, a genetic condition that causes mental retardation, infertility, and memory impairment, and is the only known single-gene cause of autism.

The study, published online ahead of print in the journal ACS Chemical Biology September 4, 2012, focuses on tremor ataxia syndrome, which usually affects men over the age of 50 and results in Parkinson's like-symptoms—trembling, ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio – New research suggests that violent video games may not make players more aggressive – if they play cooperatively with other people.

In two studies, researchers found that college students who teamed up to play violent video games later showed more cooperative behavior, and sometimes less signs of aggression, than students who played the games competitively.

The results suggest that it is too simplistic to say violent video games are always bad for players, said David Ewoldsen, co-author of the studies and professor of communication at Ohio State University.

"Clearly, ...